Zach Schonfeld is a freelance journalist and writer based in New York. He is a former senior writer at Newsweek, and the author of the fascinating book, Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth, published by the 33 1/3 series in 2020.

As a freelance writer, Schonfeld’s work has graced the pages of Pitchfork, Vulture, Paste Magazine, and more. In his book, Schonfeld delves into the unusual saga of 24-Carat Black, an orchestral and sprawling funk group from the ’70s, whose album Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth, despite being a commercial flop initially, later found its way into the samples of some of the biggest names in hip-hop.

Hi Zach, thanks for joining us today! As a freelance writer and music critic based in New York, you have an extensive background in journalism and culture writing. What inspired you to delve into writing a book about the story of 24-Carat Black’s Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth?

The album is unlike any other ’70s funk record—orchestral and sprawling, with a heady concept behind it—and I was fascinated by the group’s unusual saga. They fell under the direction of a brilliant arranger/visionary, completed just this one album (it flopped), spent several grueling years touring the Chitlin’ Circuit with a theatrical stage show, and imploded around the time Stax Records went bankrupt. Their music fell into deep obscurity, only to be found and sampled decades later by rap stars like Nas, Digable Planets, Jay-Z, and Kendrick Lamar.

I was amazed at the lack of real attention and research that had been afforded to 24-Carat Black, and the vast disparity between the group’s influence on hip-hop and their nonexistent name recognition among most people.

I also learned, after interviewing members of 24-Carat Black, that they had received no royalties or revenue from these high-profile samples. Some were still living in poverty. This brought a kind of moral urgency to the story. While I wasn’t entirely surprised by the royalty situation, I realized that the plight of 24-Carat Black was a microcosm that could help illustrate the music industry’s shameful exploitation of so many Black musicians and legends from that era.

You’ve contributed to various publications such as Pitchfork, Vulture, and Paste Magazine. How has your experience as a music journalist informed your writing process when working on your book? Were there any unique challenges or advantages that you experienced?

Well, the book was directly inspired by a piece I wrote for Pitchfork about 24-Carat Black. By the time I began the book proper, I had already done extensive research into 24-Carat Black’s story and interviewed several of the surviving members for that piece. I was inspired by their resilience, their extraordinary memories of the band, and their profound desire to have their story told.

In a broader sense, I drew on years of experience writing reported features for those outlets you named, as well as for Newsweek, where I was on staff for five years. (I got laid off the same day I found out my book proposal was accepted.) My 24-Carat Black book is a work of longform journalism—rooted in 30+ interviews and months of research—so I put those years of reporting experience to use.

In your book, you provide a deep exploration of the story behind Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth, an album that was once obscure but has since been embraced by the hip-hop community. How did you first come across this album, and what was it about its story that captivated you enough to dedicate an entire book to it?

I first came across the album the same way I discovered lots of ’70s funk gems: it was sampled by my favorite hip-hop artists. I’ve always been fascinated by sampling—fascinated by the way little fragments of melody or rhythm can be plucked from obscurity, used as a building block for someone else’s musical vision, and introduced to an entirely new generation of listeners.

I remember how my mind was blown the first time I listened to There’s a Riot Goin’ On in high school and had a “holy shit” moment when I realized those same grooves had been sampled on my favorite Beastie Boys and De La Soul albums. I’ve always been curious to know how forgotten soul legends feel about having their music resurrected in such a way.

Anyway, I became familiar with the Ghetto album in my 20s because it had been sampled by Nas, Digable Planets, etc., and I could tell the album was unlike anything else from that era. But the group’s story seemed shrouded in mystery. Not much had been written about them.

I didn’t become obsessed with researching 24-Carat Black’s story on a professional level until 2018. That year, an eerie snippet of their song “I Want to Make Up” was sampled on Pusha T’s Daytona album (produced by Kanye West). I was intrigued by that sample and wanted to know the story behind it. Once I realized they had also been sampled by Kendrick Lamar a year earlier, I decided to track down some of the surviving members and interview them for a Pitchfork article. I was stunned by the remarkable stories these musicians had carried around for forty-something years, and I believed their story offered rare insights into soul music history and record industry exploitation.

The Pitchfork piece came out in August 2018 and received far more attention than I had anticipated. Yet I felt it had only scratched the surface of 24-Carat Black’s biography. Conveniently, the 33 ⅓ series had just put out a call for book proposals, and I decided at the last minute to submit one about Ghetto. I was amazed they greenlit my proposal.

As a freelance writer, you have the opportunity to work on a diverse range of projects and subjects. How do you decide which topics to pursue, and what factors contribute to your decision-making process when selecting new writing projects?

My feature writing is a mix of pieces I conceive and pitch myself and pieces an editor assigns me. Of course, I’m more passionate about the former category. But often an editor will reach out and say “Can you write about the Jewish roots of Yosemite Sam?” or “Can you do an oral history of Raccacoonie?” and I’ll usually say sure, why not, because I need the work and I’m flattered they thought of me and it’s good to maintain those editor relationships.

As for my own pieces, it’s hard to say why my brain latches onto certain ideas. I mostly write about music, film, and digital culture. I think my writing is animated by personal obsession, curiosity, and a fascination with history—especially hidden links between the past and the present, which is certainly a theme in my 24-Carat Black book. I love unexpected deep dives, and I love investigating a good cultural mystery: Why is Creedence always the soundtrack to Vietnam movies? Why is there so much talk-singing happening in indie-rock these days? What happened to the first film adaptations of Little Women? Why do so many rappers sample 24-Carat Black’s music?

I love combining cultural criticism and old-fashioned detective work. I love delving deep into subjects that may seem silly or trivial, but reveal surprisingly rich or layered histories. I’m attracted to subjects that are a little esoteric and odd, and haven’t received the attention they deserve.

Above all, I try to pitch story ideas that haven’t been written before. I try not to pitch, like, the fifteenth Phoebe Bridgers interview of the promo cycle (no offense to Phoebe). I wrote plenty of celebrity profiles in my Newsweek days, some of which I’m proud of, but I no longer have the same access as a freelancer, and I don’t find boilerplate celeb profiles very interesting. I find it more rewarding to write about outsider figures and eccentrics, people who are on the margins of fame and celebrity. People like Lonnie Holley or legendary hoax artist Alan Abel or, well, 24-Carat Black.

Freelancing often requires a high level of self-discipline and organization. Can you share with us your daily reporting and writing routine? How do you manage your time to ensure that you can balance the various projects and deadlines you may have?

What I like about freelancing is that there is no typical day. I get to decide what story ideas I want to pitch. And if I’m working on a feature (which I very often am), it all depends on what stage the story is in—reporting, writing, edits, etc. Plus, it’s hard to predict when an editor might hit me up with an assignment unexpectedly. It’s nerve-wracking, and I don’t recommend this career to anyone who values stability, but I do enjoy the thrill of working on something different each week.

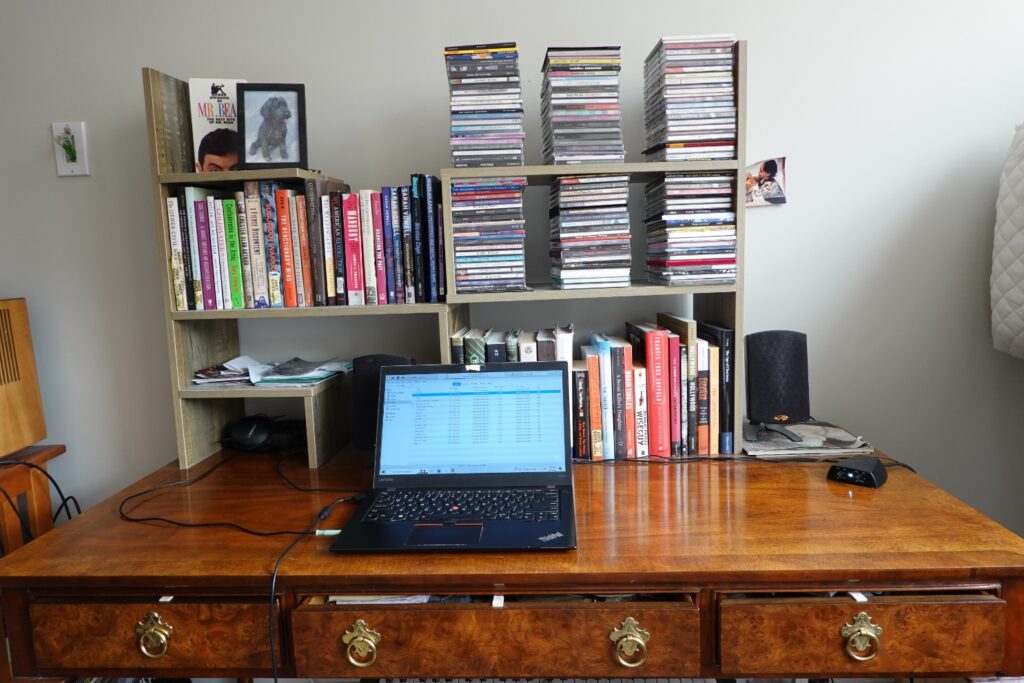

I have some general work patterns. I’m not a morning person. I wake up between 8 and 9, “commute” from the bedroom to the living room, check my email, see if there’s anything urgent to be dealt with—did I get edits back, a response to a pitch, a source writing me back, etc. I wade through my overnight messages, record my dreams into my dream diary, glance at the morning’s headlines, think about ideas I want to pitch, groggily shower. I rarely get much actual writing done in the morning. There are too many distractions, too many emails and headlines bouncing around.

Mornings are also when I frequently listen to promos of upcoming albums, with an ear towards which ones I might want to review. I receive dozens of album streams a week. It can be tedious to wade through them, but every once in a while I’ll hear something that surprises me or captures my interest unexpectedly. I listen to music (full albums, mostly) pretty much continuously throughout the day. In the afternoon, I often reward myself by listening to older albums that I already know.

Afternoon and evening are when I typically focus on the main work of the day—whether it’s doing reporting and research for a feature, writing a review, drafting or sending out pitches, etc. If I have a deadline looming, I’ll continue working late into the night. If I don’t, I often go out to film screenings or concerts in the evening—sometimes for work, sometimes for pleasure, but often the line is pretty blurred, honestly. (Is this healthy? Don’t answer that.)

As for how I manage my time, I’m pretty deadline-motivated. It’s a lot like college—you need to harness the adrenaline and anxiety of a looming deadline. I need an externally imposed deadline to keep me from falling into perfectionist purgatory. Writing is collaborative for me: I need to know there’s an editor and audience waiting on the other end. This is why self-publishing on Substack doesn’t really appeal to me, though I’m happy for other people who make it work (except Bari Weiss).

You’ve contributed to many well-known publications. How do you adapt your writing style and voice to suit the different audiences and editorial guidelines of each publication you write for?

Honestly, I don’t think my writing style and voice fluctuates much per publication. If it does, I’m not really conscious of it. I do adapt my writing style depending on the type of piece. If it’s an album review, I’m using a more analytical, critical tone and (mostly) avoiding first-person statements. If it’s an essay for a blog-adjacent site like Hell Gate, I’m writing in a more conversational, voice-y tone. If it’s a longform feature, I’m using more detailed, descriptive language.

Also, some publications put spaces around an em dash and some don’t.

In your experience, how has the landscape of freelance writing evolved since you first began your career? Are there any trends or changes that you believe have had a significant impact on the industry and the work of freelance writers?

I’ve been a full-time writer/journalist since 2013 and a full-time freelancer since 2019. That’s not long in the grand sweep of the universe, but in digital media years, it feels like centuries. Everything’s changed. The industry has contracted; private equity vultures have gutted local papers and alt-weeklies; viral empires have risen and fallen; magazines have shuttered and the ones that survive have endured devastating, near-annual layoffs. So many questionable trends have emerged and then faded: slideshows, quizzes, “curiosity gap” headlines, Facebook algorithms, “pivot to video,” etc. And now the arrival of A.I. in journalism is ominous on an ethical, economic, and existential level.

I particularly miss the blog era. I miss weird, irreverent websites that published funny essays and didn’t care about chasing trending topics, like The Awl and The Hairpin and The Toast and Wondering Sound and Gawker (RIP) and Deadspin (still exists, but in diminished form) and Gothamist (ditto) and so on.

What gives me hope is that, amidst all these sea changes, people still seem to crave good writing and human (not A.I.) perspective and old-fashioned storytelling. Lately, I’ve been heartened by the rise of independent, worker-owned publications, like Hell Gate and Defector, and nontraditional publications like Dirt, which publishes really compelling work. Lastly, I feel enormously lucky and privileged to be able to do this for a living and, given the present state of the industry, I have no idea how long it will last.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Bram Stoker. I’m fascinated by Dracula and the surrounding lore. Stoker wrote by night while working as a secretary and director of the Lyceum Theatre, and he never lived to see his masterpiece’s cultural impact.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

Lately I’ve been immersed in a detailed biography of Francis Ford Coppola (Coppola by Peter Cowie). I often admire uncompromising artists who are willing to risk it all for their creative vision, and Coppola definitely falls into that category. I love reading about the insane sacrifices he made to get Apocalypse Now and One From the Heart made—perhaps just a precursor to the sacrifices he’s now making to get Megalopolis made.

Also, not a book, but lately I’ve been spending a lot of time doing archival research into my ancestry and my great-grandparents’ lives, for reasons both personal and professional. This week I was reading an oral record of my great-grandmother’s sister’s experiences surviving the Bialystok pogrom of June 1906.

No Comments