Born and raised in Reno, Nevada, Willy Vlautin is the author of six novels and is the founder of the bands Richmond Fontaine and The Delines.

Vlautin started writing stories and songs at the age of eleven after receiving his first guitar. Inspired by songwriters and novelists Paul Kelly, Willie Nelson, Tom Waits, William Kennedy, Raymond Carver, and John Steinbeck, Vlautin works diligently to tell working class stories in his novels and songs.

Vlautin has been the recipient of three Oregon Book Awards, The Nevada Silver Pen Award, and was inducted into the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame and the Oregon Music Hall of Fame. He was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and was shortlisted for the Impac Award (International Dublin Literary Award). Two of his novels, The Motel Life and Lean on Pete, have been adapted as films. His novels have been translated into eleven languages.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Willy, great to have you here with us today! You’ve described yourself as being inspired by both songwriters and novelists like Willie Nelson, Raymond Carver, and John Steinbeck. What is it about these artists that have influenced your work, and what do you think they have in common?

Willie Nelson is my personal saint because he was the hippie that made it into my house. He was the only hippie lefty long-haired Django loving man that my mother accepted. She was seriously conservative but somehow Willie got a pass. No one else got a pass but he sure did so I’ve always admired him for that and he’s always been my favorite guitar player. Since I was seven or so he’s been my guitar hero.

Carver made a lot of sense to me as a kid stylistically but most importantly because so many of his stories were about alcoholic men carried by women. Those were stories I knew and before reading Carver I didn’t know you could write stories like that. Stories of people circling the drain in a very working-class undramatic yet dramatic way. His books gave me permission to tell the stories I could tell.

Steinbeck, well I was taught six of his novels in junior high and high school. I don’t know what was going on in the Reno school district at the time but Steinbeck was king. So I was spoon fed him at an early age and I seriously loved him. From the beginning I wanted to write working class stories and he was my map of how to do it. As a kid I had a picture of him by my bed, next to pictures of The Jam and The Clash and Rank & File and X. I thought of him like that, a hero.

Ursula K. Le Guin has described you as “an unsentimental Steinbeck” and Lidia Yuknavitch has called you a “real and profoundly useful saint.” How do you feel about these comparisons to such revered writers, and how do you approach writing in a way that is both empathetic and unsentimental?

Ah man, it’s lucky when you hear something like that. They are both heavyweights. I remember meeting Ursula and saying to myself don’t swear, suck in your gut, try to act smart. Jesus, she was the best. Always so tough and outspoken and a such beautiful writer. I can’t say enough great things about her. And when I met Lidia I did the same thing.

I told myself don’t swear, suck in your gut, act smart, and then she gave me a big momma bear hug and looked at me like a guru and we were instantly friends. I swear after being around her for less than an hour I would have robbed a bank for her. She’s just got that thing. Again an amazing writer and person. The Northwest has been lucky to have such great writers and protectors of literature and libraries.

And on empathy, novels to me are about empathy, to live inside another’s world. That’s why it’s the greatest art form and why it’s brought me so much comfort. If you find the right book you’re not alone in the world anymore. And on being sentimental, well, I try not to be sentimental because I’ve been raised and taught never to be. It probably wouldn’t hurt my mind to be a little bit more sentimental. God knows it needs help.

Your novels often focus on working-class people and their struggles. What draws you to these stories, and how do you approach writing about characters who are often overlooked or marginalized in our society?

As I said early it didn’t hurt that I was taught so much by Steinbeck or taught The Jungle while listening to The Jam on repeat. I think I knew early on that life could be tough. My mom struggled. She had a hard time mentally and was left with two little kids, was nearly thirty, and hadn’t had a real job before. So she had to fight it out. She was tough. She got a job, kept us afloat, and got paid less than men, was sexually harassed by her male co-workers and bosses.

This went on for years and before she got a boyfriend, it was me and my brother who she gave the blow by blows to. So when I started writing I always thought about her situation. Why can’t she be a hero? To me it’s heroic not to give up. Why can’t a janitor be a hero or your favorite waitress? And sadly, the truth is I was a janitor and for years worked in warehouses and painted houses. It was all I knew to write about.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

You’ve had two of your novels adapted into films, The Motel Life and Lean on Pete. What was it like to see your work translated into a different medium, and how involved were you in the adaptation process?

I wasn’t that involved. Mostly I just showed both directors around. For The Motel Life I took them around Reno and for Lean on Pete, around Portland. Both experiences were great. I love Andrew Haigh, who did Lean on Pete. He’s become a friend. He’s a serious ace. I didn’t write the screenplay for either so I was pretty hands off that way. I’d been hired once to write a screenplay and I spent six months stewing over it, and when I sent it off I got a check but I never found out if anyone had ever read it. After that I decided to stick to novels.

Can you tell us a bit about your latest novel, The Night Always Comes, and what inspired you to write it?

Six or seven years ago I was driving on the outskirts of Portland and I pulled over and counted the industrial cranes downtown. There were thirteen, meaning thirteen new buildings were in the process of going up. Portland had become a real boomtown. I have an office in a neighborhood called St. Johns, an old working-class neighborhood. I started seeing the mom-and-pop businesses there selling out.

At one point on the main drag nearly half of the businesses were closed. If you were from out of town you’d have thought it was a neighborhood in a state of failure. But the opposite was true. The old businesses had sold out for a payday and the new owners were waiting for permits to tear the old buildings down. The problem was the county was overwhelmed with permit requests so for months and months they stayed vacant. It was crazy.

From my office I can see five new apartment buildings that have gone up in less than seven years. Housing prices in Portland have gone up four times in less than twenty years while minimum wage has gone up only twice. So here you have all these new apartment buildings popping up everywhere and at the same time suddenly people are living in tents on city sidewalks.

Semi-permanent tent communities began appearing. Hundreds of them. For a while St. Johns had guys living in tents on the sidewalk outside this new apartment building. The guys were all under forty. People were walking in the street to avoid them because they were young and partying. It was hard to wrap your head around. It felt out of control.

I started thinking about how working-class families would deal with this explosion of growth and housing costs and homelessness. What if you were barely getting by before this boom? What do you do then? I decided I’d pick one dysfunctional family and see how they dealt with it. That’s how it started. I knew I wanted the book to have a real sense of panic to it. I framed it that way to give it that sort of feel. Very panicky and noir.

All over the West cities are struggling with this: explosions in growth and housing prices and homelessness. Beat-up working-class houses are suddenly out of reach for the people they were built for. And where I got stuck is, if the true American dream is home ownership, then what are families to do who are spoon fed that idea from birth? And who are all these people who have the money to buy these houses and rent these apartment buildings? And where are they all coming from?

The Night Always Comes explores the themes of the American dream and the impact of gentrification on working-class lives. What drew you to these themes, and why do you think they are important to explore in literature?

Literary communities and publishers have always been a bit hesitant to embrace working class fiction. Maybe it’s as simple as that the buying audience doesn’t want to read them. The buying audience is usually middle class to upper middle class. Working class people don’t often read novels and if they do, they don’t often want to read working-class stories. But to me, they are the most important stories of all. They have always been my favorite stories to read anyway. They always bring me the most comfort.

The novel has been described as a “soulful thriller for the age of soulless gentrification.” Can you speak to the noir-ish aspects of the story, and how you balanced the thriller elements with the deeper, more emotional aspects of the story?

I’ve loved noir for a long time. I was introduced to it by Black Lizard Press when I was in my early twenties. That’s how discovered Jim Thompson, David Goodis, and Charles Willeford. Eventually I read most of the books on Black Lizard. I’ve always thought, in general, that noir was psychologically damaged writers writing about psychologically damaged characters.

All with a sense of failure and panic and circling the drain in the blood of them. I loved those books. They were short and wild and undone. They hit a real nerve with me. As I’ve gotten older, crime writers like George Pelecanos have meant a lot to me. Pelecanos writes real political working class novels. To me writers like that really keep working class stories alive. They just frame it as a crime.

For The Night Always Comes I tried to do the same. Make it nerve wracking and fast and edgy but also I wanted it to be a story about one family’s struggle to navigate getting priced out of their neighborhood while also struggling with their dysfunction and inability to work together.

The Night Always Comes is your sixth novel. How do you feel your writing has evolved over the course of your career, and what have you learned about yourself as a writer?

I guess at times I think I’m doing better at it and other times I’m not so sure. I’m always surprised how hard each one is to write. How I always take a left turn when I should have gone right. The problem is, in writing, you take a wrong turn and a year of work goes by. Those are hard days when you realize you should have stayed left but you didn’t and now you have to shelve hundreds of pages of work.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Ah there’s a lot but right now tonight, well, Lucia Berlin. I would have loved to have met her and taken her out to dinner. Or Jean Rhys. And Jim Thompson. I’d love to see how that guy’s mind worked. He was a wild one. Maybe Frank O’Conner, that guy wrote such great short stories. Primo Levi too, James Welch and William Kennedy. Charles Willeford and Flannery O’Conner. I could go on and on.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

Right now I’m on a huge Robert Laxalt kick. He was a Basque Nevada writer and I’m going through his whole collection. I’ve also been obsessed with Claire Keegan’s novel Small Things Like These. It’s my favorite book of the last few years. I think I’ve read it three times and listened to it once. I like books about boxing and I just read Kellie by Roddy Doyle and Kellie Harrington. It’s amazing. I love Roddy Doyle. A friend of mine just got me a Ross MacDonald novel. I’ve never read him so that’s up next. Also I’m reading poetry by Joe Millar and Geno Leech, a cool poet/fisherman from Washington State.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

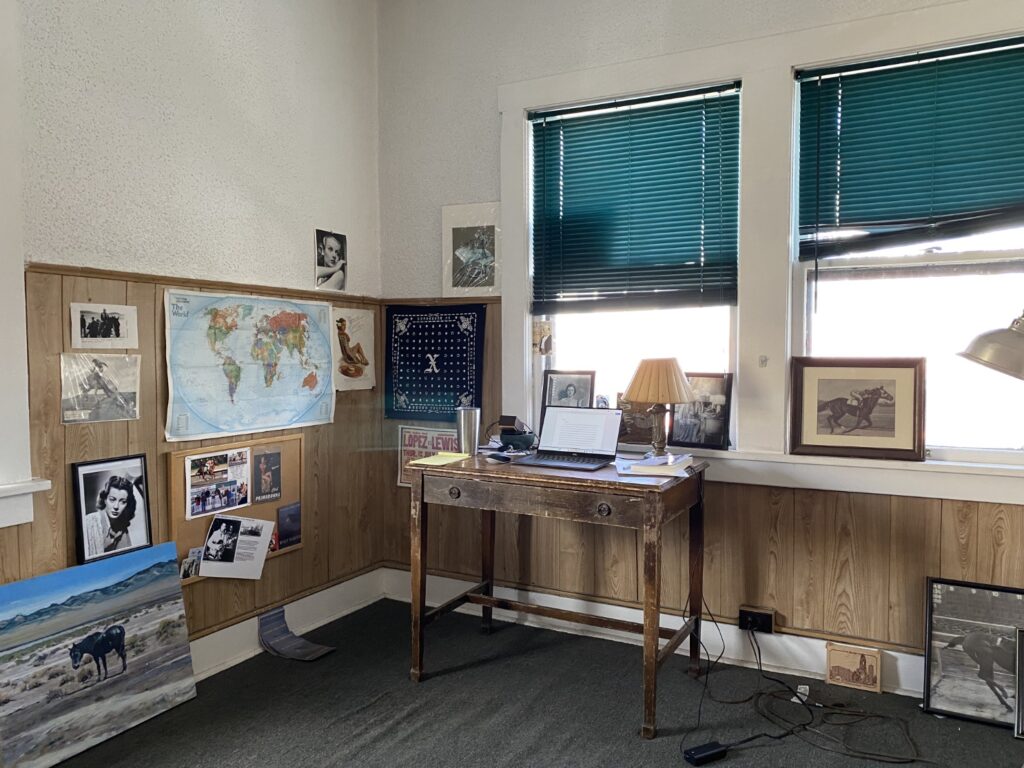

Like I said I have a great office on the second floor of this old building in St. John’s/Portland. I overlook a bar called Slims. They have benches outside it and I can see guys drinking and smoking from eight in the morning. It always boosts my confidence that I’m working and not there. It makes me feel good about myself! Next to the bar a guitar shop just opened and one of my oldest friends works there so I’m pretty set. In the room itself I have a desk and a couch. The great writer Barry Gifford once told me all you need is a desk and couch. He’s smarter than me so I took his advice.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments