Brian O’Hare is a graduate of the US Naval Academy and former Marine Corps officer. His career began in a Baltimore bar, where legendary director John Waters cast him as a convict in Cry Baby. Currently, he’s an award-winning writer and filmmaker living in Los Angeles.

His work has appeared in War, Literature and the Arts; Hobart, Electric Literature and others, and has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes. Most recently, National Book Award winner Phil Klay awarded Brian Syracuse University Press’ 2021 Veterans Writing Award for Surrender—his book of short stories published in November 2022 by Syracuse University Press. He was named a Writing Fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and served as Visiting Writer at CUNY/Kingsborough in Brooklyn.

In March 2023, along with literary icons Tobias Wolff, Tim O’Brien and Richard Bausch, Brian’s book Surrender was read as part of a WORDTheatre (Los Angeles) event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam war. He’s at work on his debut novel.

Hi Brian, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, great to have you here with us today! You have an incredibly diverse background, from serving as a Marine Corps officer to producing films and writing fiction. How have these different experiences influenced your writing and storytelling?

Hello! Thanks for having me. I’d say that my diverse background (and more importantly the people I served with, while part of those diverse worlds) provides the foundation or the ‘seeds’ of my storytelling. One of the great things about being a Marine is the incredible diversity—the US military is, in my opinion, the most diverse tribe in the history of humanity.

The interaction of very different Americans, living in close quarters, often under very stressful conditions, makes for dynamic storytelling—representing an infinite number of voices and experiences. For me, the Marine Corps was a transformative experience.

On one hand, the Marines gave me the discipline necessary to be a successful writer—but it was also in the Marines that I developed my strong sense of ‘compassion’ for humanity— for the struggles and joys that we all experience as human beings. That we’re much more alike than the media or politicians might have you believe. The Marine Corps gave me that gift—it’s a big part of my ‘voice’ as a storyteller.

Your book Surrender has been compared to Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried and features stories about the American hero myth. What inspired you to write about this theme, and what do you hope readers will take away from the book?

Surrender relates to ‘surrendering the myth’. We’re all subject to myth: personal, familial, tribal, institutional, national, etc. ‘Myth’ is essential to who we are as humans. They inform and shape our identity. But when myths are accepted as ‘truth’, unquestioned, unexamined, they can be destructive.

Growing up, my father was this larger-than-life figure, a character out of a comic book or Hollywood movie—equal parts spaghetti-western era Clint Eastwood and The Honeymooners Jackie Gleason, all mid-century New York City Irish cool, who could talk like nobody else, who flew 307 missions as a Marine pilot in Vietnam, who was not only shot down, but who had to pry his canopy open with his survival knife as he was plummeting into Danang Harbor.

As a childhood friend recently observed: Your father was the ‘shit’ and everyone knew it. Indeed he was. And, yes—everyone knew it. Especially me. And when he hitched his considerable personal mythology to that of the United States Marine Corps, an institution with a mythology rivaled only by the world’s great religions—I was hooked. I became a ‘true believer’.

It was almost ‘abusive’ in a way—the expectation that I live up to those mythologies was obviously doomed to failure. And when my father died from Agent Orange related prostate cancer at age 56, that got me asking questions, if only subconsciously at first, about what it meant. Those mythologies. And whether it was worth dying (horribly) for.

By that time, I was in my 30s. I’d served those mythologies faithfully, as the loyal son, the football team captain, the Naval Academy midshipman, the Marine officer, as a father myself. And more important, what mythology was I passing on to my own kids? I want to ‘free’ my kids from me, from my mythology—so they can be unburdened; liberated. I want to break the chain. The mad part is that I’ll always be a ‘true believer’—in my father, in the Marine Corps, in America—even when I know that it’s part fantasy. As a takeaway, I want readers to question their own relationship to the mythologies they hold. Ideally, to free themselves.

The characters in Surrender struggle with reconciling mythology with reality and finding meaning in a chaotic world. How did you approach crafting these characters and their stories, and what challenges did you face while writing the book?

Hopefully, I’ve approached each character with truth. With compassion. Even the so-called ‘antagonists’ in the stories. We’re all struggling. Men in particular, to the stubborn tropes/mythology of ‘masculinity’. And while heroes emerge, there is a price, often a slow, painful death, associated with upholding those myths. We become slaves to mythology.

In Surrender, the battalion commander character, ‘Mad Mike’ Madigan, the football coach, Coach Auger—are not ‘good people’ on the surface, they ‘torture’, make life hell for protagonist Francis Keane. But in crafting those characters, I had to discover ‘the innocence of the monster, the cunning of the innocent’—what made them human, and relatable—not just rehashing some cartoony ‘idea’ of good and bad.

Compassion is key—we see this in the work of the great writers: James Baldwin in Another Country. Soviet writer Vasily Grossman in Life and Fate. They have such compassion, almost Christ-like, for the people that ‘torture’ them, at least in their writing. Profound writers, both worthy of emulation.

The challenges were infinite—far too many to mention here. But mostly it boils down to believing in yourself and vision and what you have to say—in the face of overwhelming opposition. Making people see your vision too. That’s tough.

The book has been awarded the Syracuse University Press’ 2021 Veterans Writing Award. How did it feel to receive this recognition, and what impact do you think it will have on your writing career?

Writing is a profoundly lonely process. We labor in obscurity, for months, years even. From start to finish, Surrender took me almost seven years to complete. That’s a long time—to keep moving forward, often unrecognized and unappreciated. So to have National Book Award winner Phil Klay and Syracuse University Press award me the 2021 Veterans Writing Award was…other. Indescribable. As writers we have to be content writing for ourselves.

The process has to be the reward because there is no guarantee of any success or recognition. Ever. And that’s a cold, hard fact we all have to wrap our heads (and our egos) around. This thing of ours, this writing, this storytelling, as amazing as it is—has to be a ‘sickness’ or a ‘disease’ for the writer. Otherwise, you’ll be miserable—always. It’s a rough ride.

As my mentor, the great Jim Krusoe says: “You don’t have to be happy, you just have to write.” Truth. What impact the award will have on my career is another mystery. It definitely opened doors—or at least allowed me to get my foot caught in the door. I just did a reading of my work with Los Angeles’ WORDTheatre—along with literary giants Tobias Wolff, Tim O’Brien and Richard Bausch. A-list actors such as Bill Pullman, Sharon Stone and Chris Gorham (and others!) read our work. That too, was…other.

Easily one of the high points of my life. To be able to hand Tobias Wolff Surrender. Right now, I’m a rookie who came off the bench (and obscurity) to hit a game winning ‘walk-off’ home run for the Dodgers, to have his back slapped by Hall of Famers. Who knows what the future holds?

Your fiction has been published in a wide range of literary journals and magazines. What is your process for submitting your work and finding the right publication for each story?

For me, learning how to ‘properly’ submit work was a tough curve. Initially, I submitted my work everywhere—without a thought to whether it was a good match or if it was worth submitting. ‘Throwing shit against a wall to see what sticks’ might be a better description of my approach. Unsurprisingly, I got a lot of rejections. (Still do! Make friends with it.) Maybe 200? 300?

Until that first acceptance—which was…exhilarating. But after a while, it dawned on me that if I’d spent, months, years even, writing a piece, raising it like a beloved child to send out in the world, that work deserved the best home possible. Around this time, given my experience with film festivals, which have a definite ‘hierarchy’—with Sundance, Toronto, Berlin etc. at the top—literary journals had a corresponding hierarchy too, with The New Yorker, Paris Review, Harpers at the top of the heap.

So I researched online, discovering a ranking system, an almost ‘scientific’ criteria—circulation, Pushcart winners, pay etc.—and created a list based on that. Tier 1, The New Yorker, Harpers, The Atlantic, was elusive—they wouldn’t even acknowledge I’d submitted, so I started with Tier 2. Once that was exhausted, I moved on to Tier 3 and so on down the line, until the piece found a home. Along with this, I kept a spreadsheet, listing every submission and what resulted—to include comments from staff/editors upon rejection for future submissions. There’s even a hierarchy of rejections! This is important—not only for your sanity (you must celebrate the small victories!) but patterns start to emerge too, which you can use.

Lit mags have personalities, like people, and certain personalities are naturally more receptive to your specific ‘voice’ or flavor of storytelling. And from that, you hopefully develop a ‘relationship’ with these lit mags—even in rejection. A ‘dialogue’ develops. It may only be a toehold, but even a toehold can lead to summiting the mountain. This is a game of discipline. Of moving forward every day, if only by inches.

Your writing has been described as spare and unsentimental, yet with a powerful emotional impact. How did you develop this writing style, and what writers or works have influenced your approach to storytelling?

The ‘secret’ to learning to write is simple: Read. Write. Be patient. That’s it. As such, I read voraciously. I challenge myself. The classics—Dostoyevsky. Trollope. Hurston. Wharton. Himes. Tolstoy. Salinger. The Brontës. Harper Lee. While many of those, especially the 19th century writers, go against this ‘spare’ ethos, they all have something to teach.

One of the most powerful things about books is that it’s an ongoing ‘conversation’—though a writer may have been (physically) dead for centuries, their spirit, in the form of their artistic voice, is eternal. Charlotte Brontë is still very much my teacher. I like the spareness of the 20th Century Americans: James M. Cain. Carver. Chandler. O’Hara. Charles Portis.

Given these influences, my writing has a contemporary ‘brevity’, that ‘spareness’, but hopefully retains something of the soaring emotions or ‘search for the Divine’ as I like to call it, that beats in the hearts of the ‘older’ writers—the Brontë sisters especially. I suppose I’m trying to write literature masquerading as pulp. I always want the work to be ‘accessible’, yet with an undeniable emotional punch.

As someone who is currently working on their debut novel, can you share any details about the book, and how does the process of writing a novel differ from writing short stories?

Initially, I began writing short stories as a way of doing ‘backstory’ or ‘homework’ for a novel idea I had. After a while, three years maybe, an interconnected world developed, with recurring characters appearing in different stories, each with their own arcs. It was a practical exercise as well—I figured if I couldn’t write a compelling 15 page story, I sure couldn’t write a compelling 250 page novel. And, not wanting to diffuse whatever ‘magic’ lives, or struggles to live in my novel, I can’t talk about what it’s about, other than my exploration of ‘mythology’ continues, only deeper.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

As the late (and great) Joe Strummer, leader of the band The Clash, famously said, (aka ‘Strummer’s Law’) “No input, no output”—which to me means, without constant inspiration, whether that be good writing, film, music, poetry, painting, conversation, whatever, the input—you’re not able to output good work. So I start each day, with a meditation session, a diner mug full of strong, black, good coffee and a chapter (or two) of inspiration in the form of a book, usually while listening to music. (Early jazz works well for me.)

I’m best in the morning, so I spend the next few hours writing. I do this until the tank runs dry, and then switch to the more mundane (but no less important) matters of answering emails, etc. Exercise, which has become a part of my existence due to the Marines, provides a good counterpoint to hunching over a computer and the brainpower/creativity that’s required.

While exercising, a different part of my brain takes over, and my subconscious is often able to solve creative problems or manifest inspiration. Then it’s a movie (I’m a Criterion channel fiend) for more input/inspiration, or maybe some good beer/whiskey and conversation with friends, then reading again before bed. Though I fancy myself spontaneous, I’m really more of a ‘grinder’—I keep moving forward, always, regardless of circumstances. Structure is important. Routine. Maybe that’s a Marine Corps thing. Whatever it is, it works for me. Discipline, in whatever form, is essential for any creative endeavor. Creation ain’t for the faint of heart.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Hm. Great question—if I had that magical power, it would be tough keeping me from talking with just one. I’d definitely start with James Baldwin—more ‘prophet’ than simply ‘great writer’. His sense of compassion for his characters—to include antagonists, people who have viciously maligned and abused his protagonists—is absolute. A simply astounding writer.

As well, I’d talk with Soviet writer Vasily Grossman, whose Life and Fate, described as a Soviet War and Peace, is so epic and yet so human. A mind-blowing achievement. Possibly the greatest book I’ve ever read. I’d love to talk to Charlotte Brontë, author of the revolutionary Jane Eyre. It’s such a ‘modern’ work, a ‘manifesto’ almost, full of fierceness and an epic refusal to accept the status quo. Zora Neale Hurston too. There’s so many…

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

There are so many! In no particular order, there’s Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Tobias Wolff’s In Pharaoh’s Army, Richard Bausch’s Peace, Dantiel Moniz’s Milk, Blood, Heat, Andre Dubus III’s Townie: A Memoir, Siobhan Fallon’s You Know When the Men Are Gone, Atticus Lish’s Preparation for the Next Life, Phil Klay’s Missionaries, David Abrams’ Fobbit, Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, Dewaine Farria’s Revolutions of All Colors—all terrific reads by some of the most dynamic writers working today.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

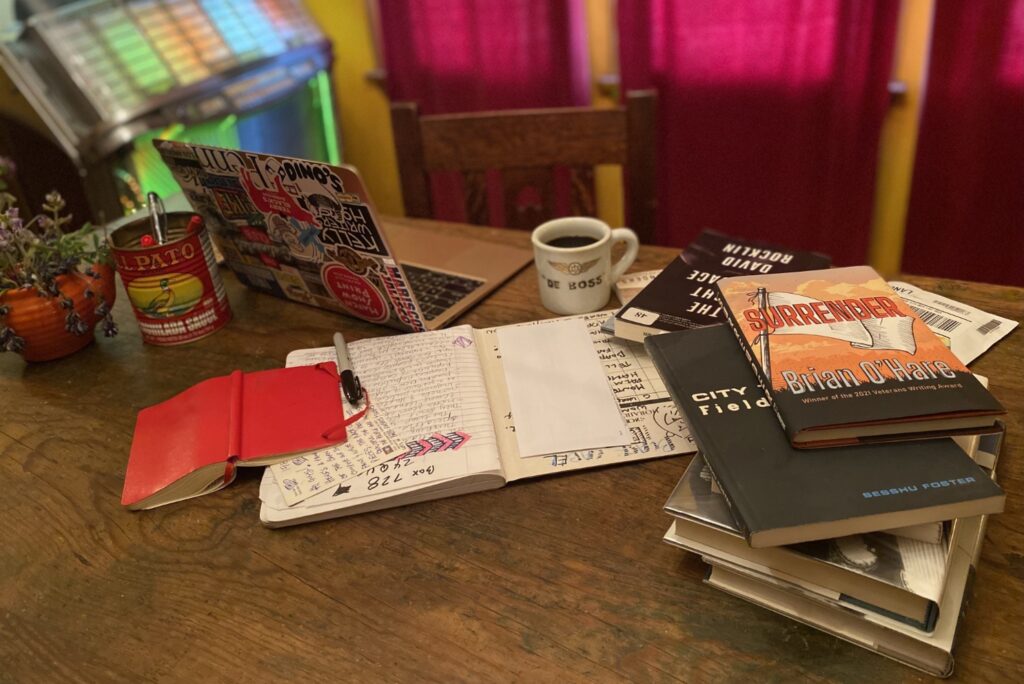

My dining room table. It’s from Mexico and it’s ancient. A lot of life, my own family’s, and others, have been lived at this table. I like to imagine mothers have given birth on my table. Rustic surgery performed. Feasts had. Drinks spilled. Its got soul. Good energy. And all that helps me write. I’m lucky to have it in my life.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments