Megan Greenwell is a freelance editor and writer, boasting a wealth of experience in print and digital media. She is currently a freelance professional, balancing her time between writing, editing, consulting, and teaching.

Megan’s extensive experience includes serving as the editor of Wired.com and interim editor-in-chief of WIRED, where she oversaw the publication’s transition to a global newsroom. She has held other notable positions such as editor-in-chief of Deadspin, launching digital features programs at Esquire and New York magazine’s The Cut, editing investigations and narrative features for ESPN the Magazine, and covering the war in Iraq from Baghdad for The Washington Post.

Megan has contributed features and essays to The New York Times, The Washington Post Magazine, The California Sunday Magazine, Slate, and several other publications, and has twice served as an advice columnist on workplace issues for The New York Times and WIRED.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Megan! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. What inspired you to pursue a career in journalism and editing, and how did you get started in the industry?

I fell into journalism accidentally: In high school, I dreamt of writing the Great American Novel, but my struggling public high school didn’t offer creative writing (or even AP English). It did, however, have a student newspaper, with a one-semester journalism class prerequisite. Greg Giglio, who taught the class, remains the most dynamic teacher I’ve ever had, and he made journalism sound like the most fun job imaginable. I was, and remain, a nosy kid at heart, and I remember lighting up at the idea that journalism allowed you to ask questions that would be rude in other contexts — or that you’d just never get the opportunity to ask. I joined the student paper, the Berkeley High Jacket, the next semester, and found myself immediately hooked on the adrenaline of reporting a big story. My first published article was about a fairly standard student protest, but my second led to me stumbling on a human trafficking and indentured servitude operation that ended up sending a prominent local landlord to prison for several years. Since then, with the exception of a variety of retail gigs in high school and work study in college, I’ve never held any other job. Mr. Giglio was right; it’s the most fun job imaginable.

Can you share some of your experiences from covering the Iraq war and the Virginia Tech shooting, and how those events have shaped your journalism experience?

When I graduated from college, I thought I would be a newspaper reporter for the rest of my life. My goal was to intern at The Oregonian, one of the papers I had grown up reading, and then get hired there full-time. (My family moved around a lot, so I lived all up and down the west coast as a kid.) My senior year, though, The Oregonian canceled its internship program for budget reasons. I vividly remember when the director of the program called to tell me the bad news; I was walking down the street in Manhattan and sank to the sidewalk, despondent.

The next week, The Washington Post called to offer me a spot in their internship program. I moved to D.C. and didn’t leave for four years. The best part of the job was that I got to cover everything: school board meetings, police shootings, Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, the long decline of the DARE curriculum in schools, and, yes, a couple of the biggest stories on the planet. The mass shooting at Virginia Tech was one of those stories that required everyone to work together; the Pulitzer Prize wasn’t awarded to an individual reporter or two, but to our entire team on the metro desk. That became a crucial lesson on journalism as a team sport. Part of my job was covering two funerals and writing obituaries for students killed in their French class, students who died at almost exactly my age. Hearing their family and friends talk about who they were and who they would have become made for a difficult but necessary lesson on finding the humanity behind any story.

When I was 23, I applied to work a temporary posting in Baghdad. Initially, the Post’s foreign editor — the great David Hoffman — said no, but someone must have backed out, so he got desperate enough to send me. I had never taken a journalism class except that one freshman year of high school, so working in Iraq became my journalism school. Almost everything I know about reporting came from those four months. I had to learn very quickly how to confirm information, how to navigate new environments, how to apply skepticism to official reports, how to cover traumatic topics sensitively, and how to find stories no one else was finding. Most importantly, my editor, Cameron Barr, insisted that I write with authority. That doesn’t mean pretending you know everything when you don’t, but trusting your own instincts on the things you do know, and communicating that confidence to the reader.

You have served as the editor-in-chief of both Deadspin and Wired.com. How have these experiences been different, and what have you learned from leading these two very different media outlets?

I would say the fundamentals of the job were the same, even though the areas our journalism covered were different. What I love about leading a newsroom is the opportunity to work with a group of brilliant people to define the identity of the publication, and that was what I set out to do at both Deadspin and WIRED. I’ve never been a topic specialist; I’ve chosen my jobs based on where I feel like I can do my best work while working with journalists who inspire me.

Being the first female editor-in-chief of Deadspin is a significant achievement. Can you speak to the challenges and opportunities you faced in this role, and what advice would you give to women aspiring to leadership positions in male-dominated industries?

I was the first female EIC at Deadspin, but sometimes people use that fact to imply that there weren’t women before me who shaped the publication far more than I ever had the chance to. Emma Carmichael, a journalist I admire deeply, was the managing editor years before I worked there, and helped make the site what it became before its private equity owners burned it to the ground — as did plenty of other women, many of whom I was lucky enough to work with. So it was definitely not a scenario in which I would ever take credit as the person who carved out space for women.

That said, women are obviously dramatically underrepresented in sports media generally, men still have an unfortunate tendency to condescend to us, and that requires strategies. My advice is always to find your people: the ones with whom you can commiserate, advocate for each other, etc. I’ve had a lot of terrific mentors of all genders, but the ones who have been most important to me have tended to be peers rather than superiors.

In 2021 left your position as editor-in-chief of Wired.com, citing “burnout.” Can you share with us what led to your decision to step down?

To be honest, that entire saga was a good reminder of why a lot of people don’t trust journalists. I was constantly seeing these trend stories about burnout that cited me as a prominent example, yet almost none of the people who wrote them ever asked to interview me. People just seemed to assume they knew what I meant without ever speaking to me. In retrospect, I regret ever using the word “burnout,” because I accidentally contributed to the creation of some phenomenon that didn’t feel like it described me at all.

In any case: The reasons I stepped down from my job were numerous and mostly too personal to blast on Twitter in the moment. A big one was that my dad had recently entered hospice and I wanted to have the freedom to travel to be with him as he was dying. Another was that three of the four colleagues with whom I worked the most closely all left their jobs within the period of a few months, and I was very sad to lose the chance to work with them. Another was that my new boss thought he might want to start with a new senior team, and asked me to reapply to the job I had been doing — very successfully! — for quite a while.

Another was that I worked really fucking hard for a very long time to be in a position where I could get enough consulting and freelance work to pay my bills without a full-time job. (This is not to undersell the importance of having a spouse with health insurance, which is a luxury I’m lucky to have.) Another was that I felt very strongly about my book idea, and I wasn’t going to be able to execute it the way I wanted to without making it my priority.

So yeah, in some sense I was burnt out, but I was also just making the right decision for my professional growth and development, as I encourage anyone to do.

Discover the daily writing habits of authors like Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Gillian Flynn with Famous Writing Routines Vol. 1 and learn how to take your writing to the next level. Grab your copy today!

Can you tell us about your creative process when editing and putting together a publication or website, and what do you look for in a good story or article?

Hm, this is a big question! In my experience, the process of writing a story is very different from the process of editing one, and both are very different from overseeing an entire publication. But since I am mostly a writer at the moment, I’ll tackle that part.

When I am first assigned to a new story, I start by reading as much as I can. For me, that includes books, academic papers, other media coverage, random blogs, Facebook posts, and more. (I never understand how reporters do their jobs without Facebook accounts — that site is a gold mine for finding sources and personal accounts. I’m working on a big story now, and the lead character came from Facebook.) Reading everything I can find gives me an idea of who I want to talk to and how I might approach the story.

From there, I start reporting. I always err on the side of overreporting — I always have far more than I can cram into a single story, even a long one, but I want as robust a view on my topic as I can possibly get before I write a word. For this story I’m working on now, I probably interviewed two dozen people, though I’m only quoting six or eight. The other dozen-plus, though, shaped my understanding of the topic in fundamental ways. Because I primarily write narrative features, reporting a story almost always means some sort of travel. Seeing the events I’m writing about firsthand is my favorite part of the process; I love noticing details in the room, getting a quote I know will be perfect, and just generally the feeling that the story still has a chance to achieve some platonic ideal, before the frustrations of actually writing start.

I begin my writing process by figuring out the structure of the piece. I’m obsessed with structure — I’ve been known to diagram the structure of features I’ve enjoyed reading in other publications just for fun. My outline is very basic, though: just a few bullet points for each section of the piece, not a decision on where every single scene or interview will go. When I sit down to write, I have to start from the beginning of the piece, writing the lede and then the rest basically in order. I’m envious of people who can write out of order, which feels very freeing to me, but alas this leopard cannot change her spots now.

Most of the time I find actual writing annoying and painful, so I always have a feeling of relief when I submit a draft. On the flip side, I love being edited (if my editor is good). Getting notes back on a story and seeing how the simplest changes can elevate a sentence or an entire piece is so fun to me.

What does a typical day look like for you?

My full-time job at the moment is writing a book, a work of narrative nonfiction about how the private equity industries affects communities and workers. At the moment, I’m attempting to split my energies between writing and reporting, which does not come naturally to me; I prefer to focus exclusively and obsessively on one thing at a time, but that’s close to impossible with major projects like this.

If I’m not on a reporting trip, I try to start every day by writing, for a couple of reasons: It’s the part of my work I least want to do at any given moment, which means I feel great when I get it out of the way, and my brain feels most clear when I first wake up. As a result, I don’t ever schedule meetings or interviews for the first part of the day, and I very rarely respond to emails.

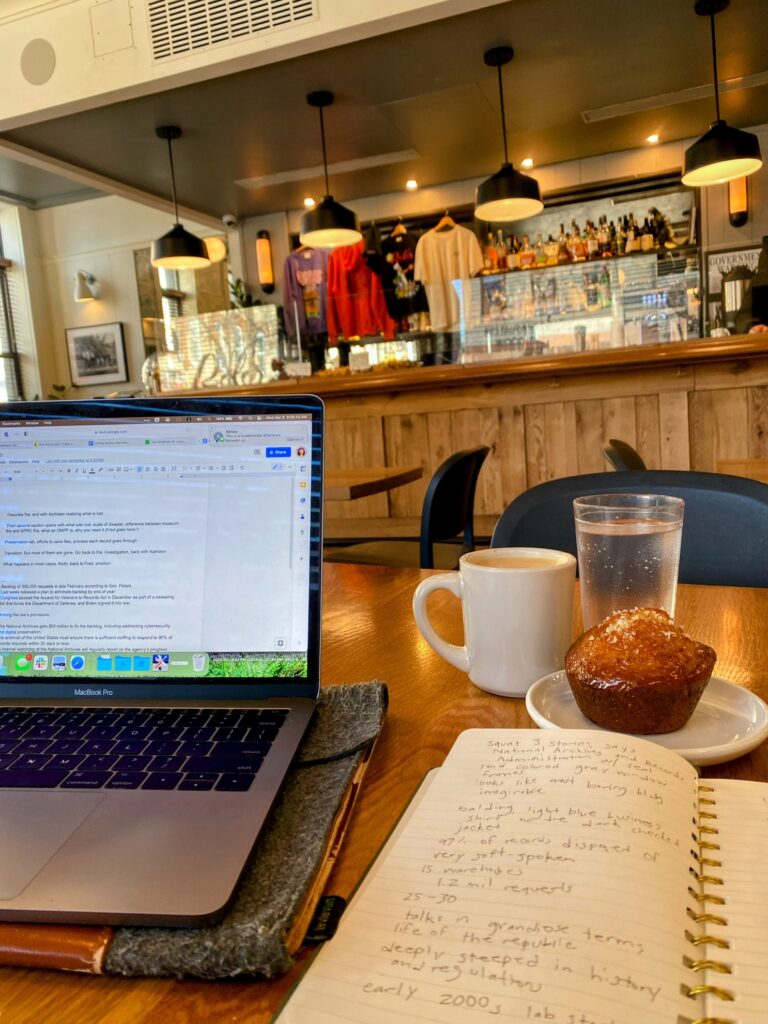

Instead, I sit at my desk or a coffee shop starting around 8 am and write as much as I can in four or five hours. Some days, that’s a few thousand words; other times it’s just a few tricky paragraphs. I almost always take a break mid-morning to take a long walk with my dog, a perfect pug named Theo, which is excellent for clearing my head. If I’m feeling stuck, walking or driving always helps me figure out how to solve whatever dilemma I’m confronting.

Around lunchtime, I generally stop writing for the day and segue into all of my other work: interviews, reading for my book, emails, and the like. Because I’m less focused in the afternoons, it’s a good time to flit among tasks that don’t require tunnel vision like writing does. I’m constantly working my way through a giant pile of books about private equity and related topics, so I always try to carve out an hour or two in the afternoon of reading or skimming. (This is distinct from my pleasure reading, which happens in the evenings, on the subway, or — whenever possible — while eating dinner alone at a bar with a nice cocktail and a dinner consisting of two appetizers.)

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Marjorie Williams’ profiles were the first pieces that made me aspire to do narrative work, and I still recommend her incredible book, The Woman at the Washington Zoo, to anyone who wants to write features. Her eye for detail was as good as anyone I’ve ever read, and her ability to cut through the noise when writing about people who had been written about a thousand times before was unparalleled. Her sentences, meanwhile, were so vibrant they practically jumped off the page. Williams died far too young, at age 47 in 2005, and I never met her, but I return to her book over and over when I need inspiration.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite reads?

I am reading so many academic tomes and boring business primers for work right now that I relish the feeling of sinking into an engrossing book like never before. In general, I read a ton of narrative nonfiction — my favorites include Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing, and Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, among many others — but I’ve mostly taken a break recently as I work on my own book. (I blame Andrea Elliott, whose book Invisible Child was so deeply reported and beautifully written that I grew so wild with jealousy I momentarily considered quitting my own book.) As a result, I’m reading almost exclusively novels. Hernan Diaz’s Trust is the best thing I’ve read in months. I’m finally on the Annie Ernaux train and can feel my soul being cracked open by The Years. I’ve recently re-read several classics by Edith Wharton and John Steinbeck, two of my favorites, and they never fail to delight. Though it will also make me wild with jealousy, I cannot wait to start David Grann’s latest, The Wager, which has been taunting me from my nightstand.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I’ve learned that I need a fair amount of diversity in my routine to make writing feel less like drudgery. As a result, while I finally have my dream office setup at home — 7-foot wide desk, ergonomic chair, laptop stand, external keyboard and mouse, good light — I only spend about half my writing time there and the other half at a coffee shop. But I’m picky about my coffee shops too: They must have background noise but not too much, music I don’t hate, and food good enough that it doesn’t make me mad to spend money to work. Also, while there are good options in my neighborhood, I actually prefer a bit of a commute to get me in the writing zone. I rotate among a few places, but I have a current favorite that I will never name lest it get too popular and thus have too much background noise.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments