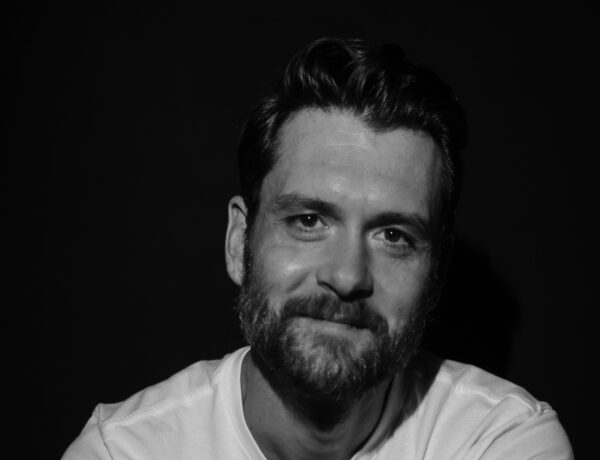

Makana Eyre is an American journalist based in Paris with a decade of experience living and working in Europe, including France and the Netherlands. Specializing in politics and history, his writing has been featured in renowned publications such as The Washington Post, The Nation, Foreign Policy, The Sun Magazine, The Atavist, and The Guardian.

Over the last few years, he has dedicated much of his time to writing a book about music in the Nazi camps, set to be published on May 23rd by WW Norton & Company in the United States, Thomas Rap in the Netherlands, and Editura RAO in Romania.

Hi Makana! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

It’s a pleasure to be here, thanks for having me. By way of introduction, I’m an American journalist who has lived in Europe for the last decade, mostly in France and the Netherlands. My work has appeared in publications such as The Washington Post, The Nation, Foreign Policy, The Sun Magazine, The Atavist, and the Guardian. For the last few years, I’ve focused much of my attention on a book about music in the Nazi camps, which will be published on May 23.

Your first book, Sing, Memory, is set to be published by WW Norton & Company. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind this book and the research and writing process?

I never set out to write about the Nazi camps or any other subject related to the Second World War. When I encountered some of Aleksander Kulisiewicz’s camp music and learned about his friendship with Rosebery d’Arguto, however, I sat stunned. That no other journalist had recounted this story in full, especially in book form, was a further shock. And yet it took me a few months to decide how or even whether to proceed.

There is a lot already in the culture about the Nazi camps, which to me means that a book about this time needs to achieve something beyond just telling a compelling narrative. What convinced me in the end was the realization that the story of Kulisiewicz and d’Arguto could advance our collective understanding of the camps in a useful and substantial way.

Save for the Auschwitz orchestra and some performances at Theresienstadt, music in the camps, especially music made by prisoners for prisoners, is a very vague phenomenon in the minds of most people. Through Kulisiewicz and d’Arguto, it seemed, I could tell a story about how prisoners of the Nazis found value in music and used it to process what was taking place around them, to attack their captors, and to recognize small joys.

Sing, Memory focuses on the story of a Polish nationalist and his transformation into a guardian of music and culture from the Nazi camps. Can you tell us more about the themes and historical context of the book?

When I began Sing, Memory, the camp music I encountered certainly fascinated me. And of course, this repertoire and the way it was saved makes up the core narrative I tell. Yet I was also drawn in by the friendship between my two main characters: Kulisiewicz and d’Arguto. In any other circumstances, these two men would never have met. They were almost thirty years apart in age. They were born in the same country (Poland), yet their communities were largely separate from each other—geographically, of course, but also culturally. D’Arguto spent much of his life in Berlin as a leftist conductor. Kulisiewicz was on a path to become a lawyer in Krakow. Despite all this, and because of Sachsenhausen, they became remarkably close. In other words, aside from the obvious themes of music, resistance, and memory, friendship also plays a major role in the book.

How did your background in journalism influence the way you researched and wrote this book?

Sing, Memory was primarily an archival undertaking. It will come as no surprise that none of the characters I write about are alive today. Kulisiewicz, for one, died in 1982, almost eight years before I was born. I thus relied heavily on archives that contain information about this time. The most useful archive about music in the camps is the Kulisiewicz Collection at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the collection that Kulisiewicz himself created.

I also relied on collections in Berlin, Warsaw, and New York, especially for the sections about d’Arguto. In addition, I did extensive interviews with scholars, several of whom have studied Kulisiewicz and d’Arguto for decades. I also spent uncountable hours with the descendants of both characters (including a nephew of d’Arguto who was 99 years old when I met him), and friends of Kulisiewicz.

Can you talk about the writing routine for the book? What did a typical day look like for you while you were working on it?

During the first two years of writing this book, I spent a lot of time reporting in the field. I traveled repeatedly to Berlin, Krakow, and Warsaw and twice to Washington DC and New York City. I mention this because it meant that I didn’t have much of a routine. Once I had most of the reporting and archival research done, I was able to focus mostly on writing. I do my best work in the morning, especially in the first few days of each week. Both while writing this book and now in new projects, I try to begin as early as possible.

On good days, especially when under the pressure of a deadline, I begin at 7 or 7:30. I then try to work through to lunch. Usually, my productivity plummets in the afternoon. Some writers can sit and produce for eight or nine hours nonstop. I’m not one of them. If I can do four or five hours of solid writing each day, I consider it a success. And though I don’t hold myself to a minimum word count to reach in a day, I do keep track of how much I’ve written and aim for four to six hundred words.

What are the most challenging and rewarding aspects of the writing process for you?

It’s no secret that for many people, myself very much included, writing is hard. There are the macro troubles like choosing the right structure. Problems that might seem more micro, like selecting the right word for a given sentence, also arise frequently. Simply maintaining discipline and sitting at your desk every day to work can be an immense challenge. In my case at least, when you find that perfect word or write a sentence that really hits true, it makes up for the struggle and, importantly, gives you the boost of confidence that you can do it again.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

I would probably choose George Saunders, who is of course, very much alive and publishes regularly. Saunders strikes me as the kind of writer who is honest and open about his work, while also being able to describe his approach in a way that’s useful to younger writers. Luckily for me and all of us, he recently wrote about all this in “A Swim in a Pond in the Rain.”

I’d love to know what you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite books you have read recently?

I recently read The Copenhagen Trilogy and loved it. At present I’m reading Colm Tóibín’s essays and Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, both of which are great. Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So is up next plus a few books by the Polish authors Hanna Krall and Krystyna Żywulska.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I work at home in a small guest room. I’ve never been much for working at cafes or restaurants, as I’m easily distracted. I try to keep the space simple and enjoy facing the window.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments