Annie Liontas’ debut novel, Let Me Explain You, was featured in The New York Times Book Review as Editor’s Choice and was selected by the ABA as an Indies Introduce Debut and Indies Next title.

She is the co-editor of the anthology A Manner of Being: Writers on their Mentors. Annie’s work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, NPR, Gay Magazine (Best of 2019), BOMB, Guernica, McSweeney’s, and Ninth Letter, and she is a contributor to Tolstoy Together: Reading War & Peace with Yiyun Li.

Annie has received a Writing x Writers Fellowship and in 2021 was named a Fellow for Mid-Atlantic Arts at the Millay Colony for the Arts. She is a recipient of the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund and an Art is Essential Grant through the City of Philadelphia. Before joining George Washington University, she taught as Visiting Writer at UCDavis, University of Massachusetts, and Bryn Mawr College.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Annie! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. Can you tell us about your debut novel, Let Me Explain You? What inspired you to write this book?

I really wanted to write the comic immigrant novel—to honor the experience of the immigrant, to celebrate it, to laugh at it a little, because it is an absurd existence of double consciousness. The book follows Stavros Stavros Mavrakis who, having been visited by a “goat of death,” believes he will die in ten days and goes about making his final arrangements, which first and foremost is emailing his daughters to tell them everything that’s wrong with them. But really, the novel is about the generations of women who stand in the long shadow of the immigrant patriarch and who demand to be seen in their complexity, queerness, selfhood.

The novel seeks to be darkly funny, at other points poignant, and to capture what it was like for me to assimilate as someone born in America but who, having lived in Greece for my early childhood, had to learn English and feminism (i.e., I didn’t think women were allowed to drive). As Marina, my favorite character says, We come from a race of people who must carry everything we own—all our words, all our stories—in our mouths.

As an editor of the anthology A Manner of Being: Writers on their Mentors, can you share your thoughts on the importance of mentorship in the literary world?

There is no single path to being a writer—it’s really an uncharted experience, even for people who come through the MFA. Mentorship is especially important for marginalized writers, or for those who have historically had limited access to writing and publishing. I remember when I first started out—as someone who is queer, first-generation to college, and from an immigrant family— I was completely mystified. I thought the only people who were writers were dead.

My father was a welder, my family weren’t big readers, and it wasn’t until college that I met any practicing writers. So it was incredibly important for me to find guides, people who were similarly dedicated to the word, who were devoting their lives to the work and the community. And, of course, it means everything to have someone say, “There might be something here, keep at it.” These days, I love connecting with emerging writers at GWU, in Philadelphia, at the Disquiet International Writing Conference, and elsewhere. It is a real privilege to witness a young talented writer reach their potential.

Your work has appeared in various prominent publications, such as The New York Times Book Review, NPR, and McSweeney’s. Can you talk about how you go about adapting your writing for different publications?

We contain myriad selves, even those of us who are voice driven. (Voice, Victor LaValle tells us, is really just an accumulation of self, aka: personality). For The New York Times Book Review, what mattered most was making visible the notion of literary inheritance, particularly for those of us who are immigrants to the page.

For McSweeney’s, I was able to play with hyperbole and humor in “Philly is Really Just Your Friend From College Who Will Always Be 3 Credits Shy of Graduating.” I do find, however, that if I’m doing it right, certain essential characteristics appear across genres and outlets—humor, curiosity, lyricism, sincerity, joy.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

As the recipient of several grants and fellowships, including the Writing x Writers Fellowship and the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, how has funding impacted your writing and creative process?

Funding puts a little more in the tank so we can keep going, and I am grateful for every bit of it! The first time anyone invested in my writing was at the Syracuse MFA, and I understood what a privilege that was—I treated it like a job. I got very Annie Dillard about it: get up, edit pages, read pages, write long into the night, bed, and start all over again.

Later, when I was on my own, I’d pay myself twenty-five cents for every hour I worked, clocking out and dropping coins in the jar after each session. But the ongoing support from organizations like the Barbara Deming Memorial, Millay Arts, Writing x Writers, and Lighthouse Works mean that for at least a little while I get, in the words of Virginia Woolf, a room of my own. Such institutions are essential in America, where we culturally tend to admire the writer, but rarely financially support her. (In places like Ireland, writers aren’t taxed!).

At Millay Arts, for instance, I wrote the first draft of my informed memoir Sex with a Brain Injury, which will be out in 2024 with Scribner. Without generous support, I don’t know that I could have ever embarked on such risky work, or even started my new novel.

Can you tell us about your writing routine and how you approach the creative process? What does a typical writing day look like for you?

My third eye tends to open at night, so I keep pretty late hours. A day job isn’t always conducive to that, so I really use my summers and breaks to throw words down. I write pretty intensely, in three-to-six-hour bursts. For years, I have kept a log of my writing sessions, noting anything from time/duration, to weather, to word count and goal, often using the space to grapple with an unresolved question or even—in the words of Annie Dillard—a “fatal flaw” germane to the draft or concept. This log is over a thousand pages now.

Sometimes, I start writing right in the document. Sometimes I pivot to mapping/outlining/putting things up on the whiteboard. Like other writers-Kirsten Valdez Quade comes to mind—it takes me an hour to really sink in, or to find Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow.” If I’m inside a novel, I usually work until I hit the end of the chapter. If I’m in heavy revision, I print out the stack, make edits by hand, then manually enter every single word back into the document so I’m honest about whether or not it should stay. This can seem intense or radical, but I find that some of my creative breakthroughs happen when I raze the work to the ground.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Probably everyone says Toni Morrison, but I’m going to say it, too. (There’s a reason the USPS put her on a stamp!) I will always be deeply appreciative of her work, her expansiveness, and how she helped to redefine the American experience. Like the rest of the world, I was heartbroken when she passed. I’ve geeked out on interviews, of course watched the documentary.

I know things like she used to wake up super early to work, that she never draws from the people in her life, that she believes in the life-saving power of literature, that she loves getting gifts—but I want the stuff she doesn’t talk about. I want to sit down with her and go through every page of Song of Solomon. I want to hear her stories and gossip and vision for America and what she thinks of this word or that.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite reads?

We could be here all day! For “The Gloss,” an interview series I launched during pandemic to spotlight women and genderqueer writers, I’ve read some amazing new work. I’ve loved talking with Rachel Heng at BOMB about her newest novel The Great Reclamation, which follows a young boy as he comes of age in the 1940s alongside his beloved Singapore. I also adore the subversive climate fiction of writers Allegra Hyde (The Last Catastrophe, short fiction) and Ramona Ausubel (The Last Animal, novel), and talk with them over at Electric Literature. I’m super excited about my upcoming conversation with Lamya H at EL on her memoir Hijab Butch Blues. Marie Helene Bertino, who I interviewed for The Believer, always gives me permission to be my weird self on the page, and I can’t wait for her newest work on being an alien!

Can you tell us about your upcoming informed memoir, Sex with a Brain Injury? What inspired you to write this book and what can readers expect?

Toni Morrison (!) says: If there’s a book you want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it. During my long recovery after suffering multiple concussions, I went seeking understanding—I didn’t know what was happening to me. I couldn’t find any answers, not in my family, nor in my queer/writing community, nor among support groups, not even in books, which are my greatest refuge. Because writing is always how I meet the world, I decided to put it all onto the page—my fears, my rage, my physical suffering, my marriage, experiences of intimacy and questioning, what it’s been like to claw my way back.

Sex with a Brain Injury weaves criticism, history, philosophy, and memoir. The work seeks to contribute to the vibrant and emerging canon of Creative Nonfiction that interrogates and expands representations of mental health, ability, and disability, particularly in relation to women and the LGBT community. But many parts of the work resist intellectualization. They insist: this is what it feels like to have been hurt in this way. This is how a marriage suffers when one of us is sick. Virginia Woolf, of course, makes multiple appearances.

I was stunned to find that in writing this book, I was forced to reckon with my own queer mother’s battle with addiction, and to recognize similarities in our suffering. My hope was that others who had incurred head trauma and were suffering from post-concussive disorder would feel less alone, more seen. What I learned as I wrote this book was just how invisible and ubiquitous the “silent epidemic” is: 3.8 million athletes, 415,000 veterans, 1.4 million concussions each year.

One out of every two people experiencing homelessness has a head injury, usually acquired before they ever lost their home. Women experiencing domestic violence can sustain more head trauma than football players but are seldom diagnosed. In the criminal justice system, a person is seven times more likely to have a head injury—before they ever step foot in a prison cell. Such revelations inspired me to co-write “Professor X” with Marchell Taylor, former inmate and businessman and the co-author of Denver legislation that calls on neurological screenings before sentencing.

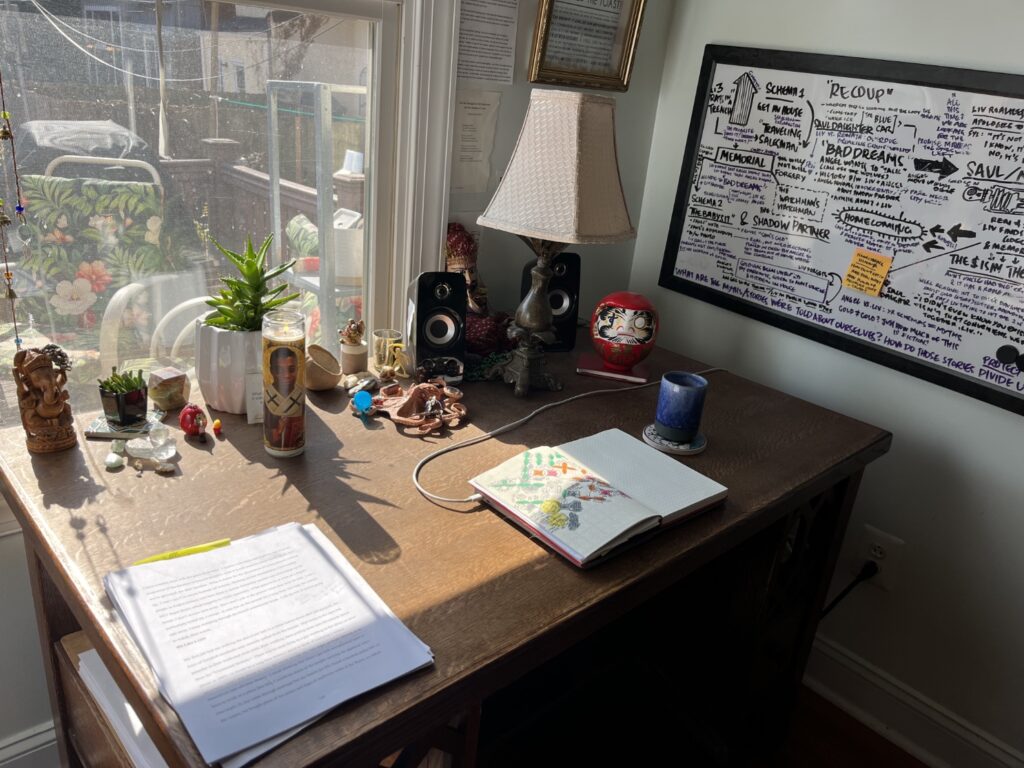

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I always write while looking out of a window. This is a way to remember that while writing is a solitary act, it is always of the world. Like most writers, I curate a workspace, routine, and practice so that I can land on the page even on a bad day.

For courage: on my desk sits a tiny pirate I found, some beautiful rocks, some plants, a photograph of Whitney Houston, a James Baldwin prayer candle, a puppet on a string, a little index card that reads “What would someone in solitary confinement want to see?”, a poem entitled, “On the Strength of All Conviction and the Stamina of Love,” and a daruma whose motto is “Fall down seven times, get up eight.”

My walls are often covered in post-its and big structural maps of the long work I’m writing and revising. Because of my post-concussive disorder, I rely on natural lighting, as overhead lighting tends to trigger migraines. I listen to music, usually on headphones, or else welcome the silence. There is usually half-finished decaf espresso in a mug, or some matcha. There is likely a rabbit or dog beneath my chair. As a reward, we have a little snack.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments