Sam Thompson is an author and creative writing teacher based in Belfast. His first book, Communion Town, made the longlist for the 2012 Man Booker Prize.

His second book, Jott, was shortlisted for the 2019 Encore Prize and his third book, Wolfstongue, won a 2022 Spark School Book Award. He recently released a new novel, The Fox’s Tower, which is longlisted for a 2022 British Science Fiction Association Award.

Sam’s work has been published in various anthologies and collections, including Best British Short Stories 2019 and on BBC Radio 4. In addition to his writing, he teaches creative writing at Queen’s University, Belfast.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Sam, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, we’re so glad to have you here with us today! Your latest book, The Fox’s Tower, was longlisted for a 2022 British Science Fiction Association Award. Can you share with us the inspiration behind this novel?

It’s great to speak to you. The Fox’s Tower is a novel for young readers about a girl whose father is stolen by foxes. She ventures into the world of talking animals to find him, and discovers an infinite forest in which the foxes have built a tower that contains a whole civilisation.

The Fox’s Tower is the second book in a sequence — the first is called Wolfstongue, and I’m currently working on the third. These books take some inspiration (and some main characters) from medieval European fables about Reynard the Fox, but the real impetus came from my own children.

We’re a neurodiverse family with some speech difficulties, and I wanted to tell us a story that was like a tool for thinking about the challenges of words, and what it means to live in a world of language, as humans inescapably do. A fantasy-adventure about animals who speak seemed a natural way to explore all that.

What was the creative process like putting together the book – from initial idea to final draft?

I usually write quite slowly, but I had a tight deadline for The Fox’s Tower, so I had to be efficient about it. Luckily that suited the book. The initial idea came fully-formed out of Wolfstongue: when I started Wolfstongue I had thought it would be a small, self-contained tale, but on finishing it I felt I had only begun to uncover a story that ran much deeper, and that my fable about talking animals was leading into big questions about how human beings relate to the non-human world.

With that in mind, and the feel of the story’s world already established, it wasn’t too hard to sketch out a storyline — though I was careful not to know exactly what was going to happen in the final act. It feels important to keep myself in the dark about one or two key points in the story until I get there.

Then, as always, it was just a case of writing it. There’s a steep time differential between sketching the shape and actually writing the book. You can easily spend a morning making an outline and several years turning it into prose. However long it takes, the process is not mysterious: put in the hours with the project, ‘turn sentences around’, learn your story backwards and forwards, write the book not once but many times. Three times, at least – once to make it exist, once to make it work and once to make it good.

How has your experience living in the South of England and Belfast shaped your writing and perspective on the world?

I was born in London and grew up in the south of England; I’ve moved between England and Ireland several times in my adult life, and for the past seven years my family and I have been settled in Belfast. Hopping between these islands hardly amounts to an epic journey, but I hope it does give a bit of useful perspective on both places.

We moved to Belfast not long before Brexit happened, and since then I’ve often been naively astounded that the British establishment could casually place the north of Ireland in such jeopardy. Most northern Irish people I know are not at all surprised: they’ve grown up knowing all too well that this part of the world is where the British national psychodrama acts itself out in the most shameful ways.

Ever since Brexit I’ve had a phrase from The Great Gatsby in my head, where Nick talks about the ‘vast carelessness’ of the privileged set. ‘They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.’ Whatever perspective I have from where I’ve lived, it’s made these lines vivid to me as a diagnosis of a particular form of evil.

Being an Englishman living in the north of Ireland certainly makes me conscious of my Englishness. It leaves me with no patience whatsoever for the fake thing that often passes for English identity — the belligerent, resentful ghoul, dripping with nostalgia for imperial sadism — but it makes me love what I think of as real Englishness all the more: the radical, egalitarian, visionary tradition of the English you can find in Shakespeare, Shelley and Blake.

You have published a variety of genres, including short story collections and novels. Can you tell us about your creative process when switching between these different forms of writing?

I’m sure there are big differences between the processes, but they are almost entirely obscure to me. I do know that for me a short story often begins as what I think is an idea for a novel: I find I don’t exactly know how to make it work, so I fold it down, make it less explicit and more elliptical, and eventually find it’s a story I can tell in four or five pages, rather than a couple of hundred. This is good news, because it saves a lot of time.

Short stories are more mysterious than novels. Hilary Mantel once claimed that it took her longer to write short stories than it did to write novels, and I find that entirely plausible. Novels can take any form and do anything, but I think it’s practically impossible for a novel not to embrace the principle of cause and effect — at some level the novel is always rationalizing, demonstrating that things happen because of other things.

On top of that, novels almost always believe in human agency — the things that make other things happen are the choices that people make. I’m not sure the same applies to the short story. Short fiction has more capacity to entertain the idea that human agency is an illusion and that things might happen for no reason we can hope to grasp.

These are big generalizations and I’m sure there are many exceptions. But I do feel as if fiction writing happens between two poles – one where we rationalize and organize and sort experience into a narrative that makes mechanical sense, and the other where we are free of logic and simply dream. Fiction would not be fiction without elements of both, but maybe novel-writing draws you more one way, short stories the other.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

Your first book, Communion Town, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. What was the experience like for you, and how did it impact your writing career?

Well, it was a huge stroke of luck for a little experimental debut novel. As a new writer, or as any kind of writer, you’re always thirsty for validation — for signs from the outside world that your work has some meaning, and that you’re not completely deluded to keep spending your time on it — so I will always be grateful to have had a dose of that validation for my first book.

Determination is the main quality a writer needs, and that has to come from an internal source. You need a lot of skepticism about external forms of approval like prizes, publications, sales: they can’t be the reasons you’re doing the work, and your sense of the work’s value has to be rooted somewhere no one else can see.

At the same time, emerging writers shouldn’t feel ashamed of needing encouragement. Unless you’re incredibly austere, you’re writing out of some impulse to engage with your fellow human beings, and it’s natural to need a response. I think one of your tasks as a young writer is to collect the crumbs of engagement, and use them to fuel your determination.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

I try to be flexible. I have a job and a family, so it’s impossible to be too rigid, and there isn’t really a typical writing day. The minimum I aim for is to spend *some* time with the work each day. Even sitting at the desk staring at the document for a few minutes, not writing but not doing anything else, is better than nothing. When I fail at even that, I start getting grumpy and know I need to do better tomorrow.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

I’m not sure I agree with the premise of the question. I’ve come to feel that wanting to meet your favorite writers is a kind of category mistake. The whole point of great authors is that they have already given you their gifts, they’ve already taught you what they have to teach. When you meet an author you admire, they turn out not to be that author at all, but an ordinary person just like you. Which in itself can be delightful or disastrous – but either way, the author, as author, stays out of reach.

It’s such an odd, strong impulse, that desire to meet the person behind the book you love. I do share the feeling that it would be wonderful to get to ask Beckett or Baldwin or Woolf or Angela Carter about their creative process — but why, really? They have already told me all about it in the most intimate detail. In my experience, meeting your favorite writers has a unique flavor of social awkwardness, and I think this is the reason: you’ve already communed so deeply that sitting across from them making small talk just feels weird.

That said, I wouldn’t mind having tea with Jane Austen.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

Recently I’ve been reading a lot of fiction that seems potentially relevant to the book I’m trying to write, so many of these books feel loosely connected, at least in my mind. Some classic science fantasy: Jack Vance’s Tales of the Dying Earth, Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun, Michael Moorcock’s Elric books – things I should really have read 20 years ago as a young geek, but which are equally wonderful to discover as a middle-aged one. A pair of solarpunk novellas by Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy, which set out deliberately to envision a gentle, hopeful future-world, and I think do a great job of it.

At the other end of the hope spectrum, Anna Kavan’s unique 1967 novel about psychosis and apocalypse, Ice, and Thomas Ligotti’s novella My Work is Not Yet Done, a most sinister horror story by a writer who, I think, genuinely doesn’t believe in human agency, or even in cause and effect. Steve Aylett’s Lint, a fictional biography of an imaginary pulp SF writer which is actually a bizarre discourse on what it means to be original (Aylett is an inspiring genius and I would recommend his book-length essay Heart of the Original on the same topic).

I’m currently reading Mieko Kawakami’s recent novel Heaven, which is excellent, but rough going because of its descriptions of bullying. And among all that fiction, I’m reading James Bridle’s Ways of Being, a fascinating nonfiction exploration of non-human modes of life and the ways in which we might relate to them.

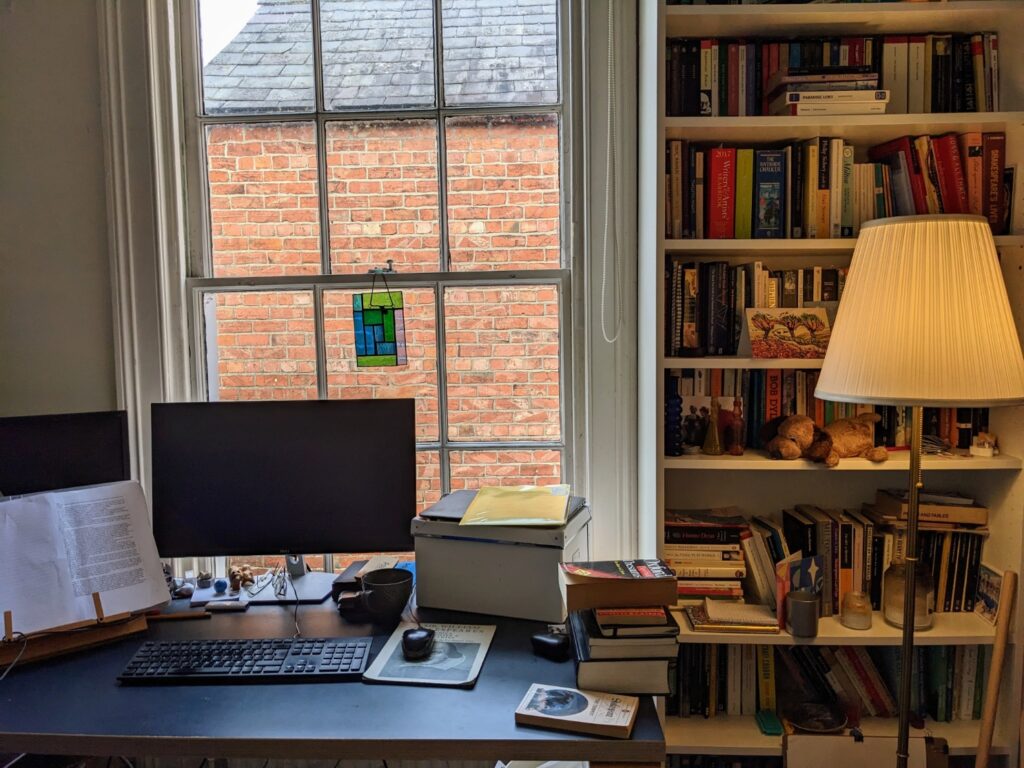

What does your current writing workspace look like?

It looks like everything I need in a writing room: a chair, a desk, a window, some bookshelves and a door that, following Stephen King’s advice, I am willing to close. My room’s door doesn’t always stay closed for long, what with children and animals wandering in and out, but it’s more than enough.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments