Jessica Andrews is a fiction writer whose work explores the complexities of identity and relationships. Her debut novel, Saltwater, was published by Sceptre in 2019 and was awarded the Portico Prize in 2020.

The novel delves into the intricate dynamics of mother-daughter relationships and the ways in which class and place shape one’s sense of self. Jessica’s second novel, Milk Teeth, was also published by Sceptre in 2022 and centers around themes of desire, denial, food, and shame.

Jessica is a Contributing Editor at ELLE magazine and a regular contributor to the Guardian, the Independent, BBC Radio 4, and Stylist. In addition to her writing, she co-runs the literary and arts magazine, The Grapevine, and co-presents the literary podcast, Tender Buttons. Jessica is also a Lecturer in Creative Writing at City University, London.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Jessica, welcome to Famous Writing Routines! It’s great to have you here with us today. Congratulations on the success of your second novel, Milk Teeth. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind the story and what you hope readers will take away from it?

My first novel, Saltwater, is about carving out space for yourself in a world that does not want you to have it. In Milk Teeth, I wanted to think about what happens when a space opens up for you but you cannot allow yourself to step fully into it.

My work often explores the impact of gender and social class on the body and Milk Teeth is about the ways in which we are taught to police our own desires. It is largely about denial and feeling shut-out of the life you want to have, but it felt important that it didn’t become a hollow book; I wanted to make the reader feel hungry.

I wrote a lot of Milk Teeth while living in a small beach town outside of Barcelona and Cataluña became the perfect setting for the novel. I wanted to capture the inherent contradictions in inhabiting a working-class woman’s body and the sticky, humid landscape served as an important backdrop to force my characters to confront the ways in which their bodies mediate their perceptions of the world.

In Milk Teeth, you examine the themes of desire, food, the body, shame, and joy. Can you talk about the research you conducted for the book and how you approached incorporating these themes into the story in a meaningful way?

My novels are fictional, but they often deal with emotional truths that I am trying to answer about myself and the world. I often begin with a knot of difficult questions that I want to untangle. I knew that Milk Teeth should be about wanting and that for myself, wanting has often been caught up in guilt and shame.

The novel has two intersecting timelines; one is a love story set in the present and the other explores my protagonist’s past experiences. They are in conversation; one timeline poses a question and the other attempts to explain the ways in which my narrator’s behaviour in the present is constructed by her past.

I found that my explorations into desire and denial were often tied to the body, and I made a list of instances in my own life when I remembered feeling bodily shame. I began to write into these memories, fictionalising them as I went, searching for a thread that would help me to untangle my narrative questions.

Beginning a novel is like that for me; I write into memories, feelings or images which feel connected in ways I do not fully understand, then I step back and begin to piece a narrative together.

Saltwater, your debut novel, won the Portico Prize in 2020 and explores themes of mother-daughter relationships and shifting class identity. How did you approach weaving these complex themes into the story, and what was the biggest challenge you faced during the writing process?

I wrote Saltwater in three separate sections; the chronological story of my protagonist’s childhood in Sunderland and her young adulthood in London, a present-tense narrative in which she is living in her late grandfather’s house in Ireland, and a fragmented section that represents the bodily nature of a mother-daughter relationship.

Initially, I planned out the novel in detail, distancing the story from my own and drawing plot and character maps, but it lacked sincerity and emotional truth. I tried to forget about writing ‘a novel’ and instead sat down and wrote what I felt compelled to each day, and the story began to grow organically.

I printed out the separate timelines and arranged them thematically on the kitchen floor. The novel is told in fragments which are linked by themes and symbols; there is an emotional, symbolic or thematic architecture, as opposed to a plot-driven narrative. The most difficult part of the editing process was finding a way to make the pieces fit together; moving one section around often meant I had to move others and it was an intricate process in that way.

People have described your prose as vivid and lyrical. Can you talk about your writing process and the role that language plays in your storytelling?

I’m interested in language and I read a lot of poetry. My favourite writers make work which is often situated in the boundary of poetry and prose, such as Eimear McBride and Garth Greenwell. I’m drawn to representations of the body in art and poetic or fragmented language often feels like the most authentic way to represent somatic experiences.

My brother is deaf and there was a lot of emphasis on language in my house when I was growing up; we always watched television with subtitles and there were often lists of words and images stuck on our fridge. We used sign language when my brother was small, which made me aware of the symbolic nature of language from a young age; I learned that there are different ways to experience the world and different systems and symbols to represent those perceptions. Language feels important to me in this way; it isn’t simply about the meaning beneath the words, the words themselves are also important.

You have an extensive background in journalism, including writing for the Guardian, the Independent, BBC Radio 4, and Stylist. How has your journalism background influenced your writing style and approach to storytelling?

My work is often located in the space between fiction and non-fiction and I find that each form offers different freedoms. Writing fiction allows me to explore an idea through symbols and metaphors, whereas non-fiction allows me to be more direct.

I think I’ll always be interested in the blurring of truth, memory and fiction, particularly with regards to the representation of working-class women’s bodies. What does it mean to capture a particular kind of body or lived experience in a novel? What does it mean to record it in a newspaper or magazine? Which form allows me the most freedom to articulate an emotional truth about the way I have lived?

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

You’re also a Contributing Editor at ELLE magazine and a Lecturer in Creative Writing at City University, London. Can you talk about the role that teaching and mentorship plays in your own writing process?

I think of writing as opening or deepening an emotional, intellectual or political space for people to inhabit. Teaching is often about guiding students to the spaces that other writers have opened, showing them the potential that those spaces might offer them, and then allowing them to enter spaces on their own terms. To me, an important part of being a writer is also being a listener, and teaching allows me to listen to other peoples’ stories, ideas and perspectives.

On a practical level, teaching definitely improves my editing skills. It’s often useful to be asked to justify or clarify the use of certain techniques, as opposed to relying on intuition. Being asked to justify why a particular technique is or isn’t effective allows me to be reflective on the use of those devices in my own work.

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

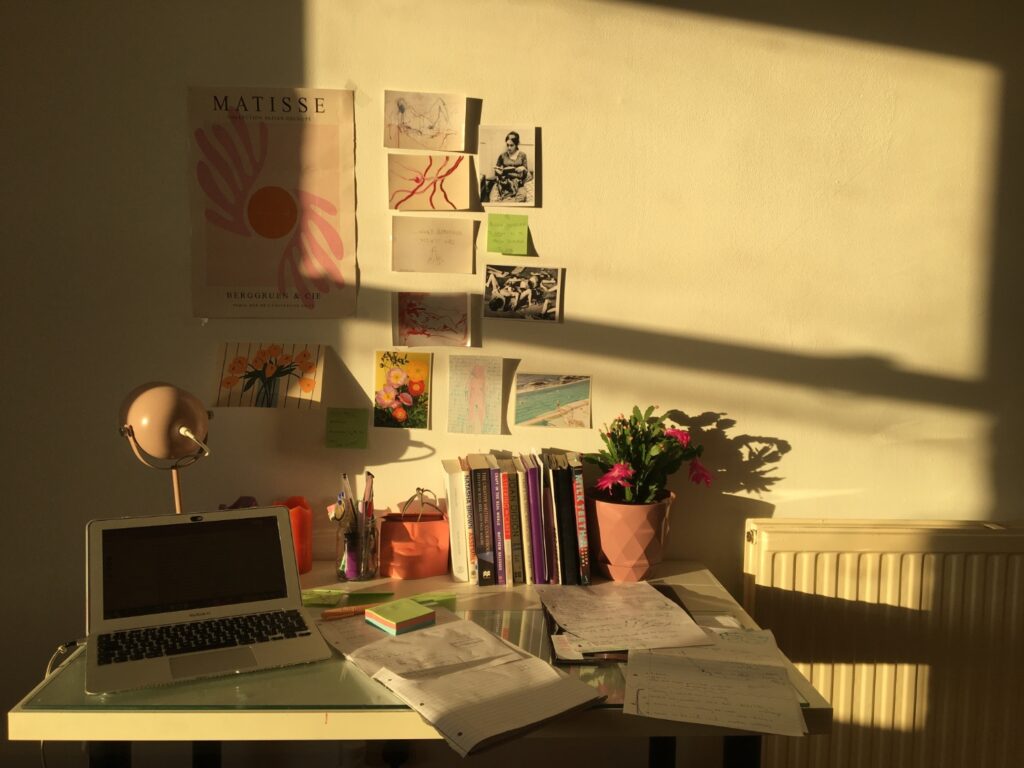

When I’m working on a big project like a novel, I tend to write in my journal before I begin work, in order to clear my head. I often read a few pages or lines of a book that I admire, which makes me feel excited about writing and ready to begin. I tend to work to word counts and will sit at my desk for as long as it takes me to reach my daily goal.

I also think it’s important to develop your ideas in other ways by reading, visiting exhibitions, watching films, having a conversation or just going out and experiencing the world. It requires drive and perseverance to finish a big project, but I’m learning that it’s equally important to give yourself time off and to engage with other people’s work in a way that makes ideas feel expansive.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

I’m a visual person and tend to make physical moodboards when I’m writing, which means I’m often drawn to the processes of visual artists and the ways in which they archive their lives. I would love to talk to Carolee Schneemann about her Life Books or Louise Bourgeois about the visual symbolism she developed to articulate recurring themes within her life.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite reads?

I’ve just finished Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü, translated by Maureen Freely. It is the first of Özlü’s novels to be translated into English from Turkish and I thought it was brilliant; I would love to read more of her work. I’m also enjoying the Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen, translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman and Happening by Annie Ernaux, translated by Tanya Leslie. I’m excited to read Bhanu Kapil’s new work, Incubation: A Space for Monsters and Was it for This by Hannah Sullivan.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments