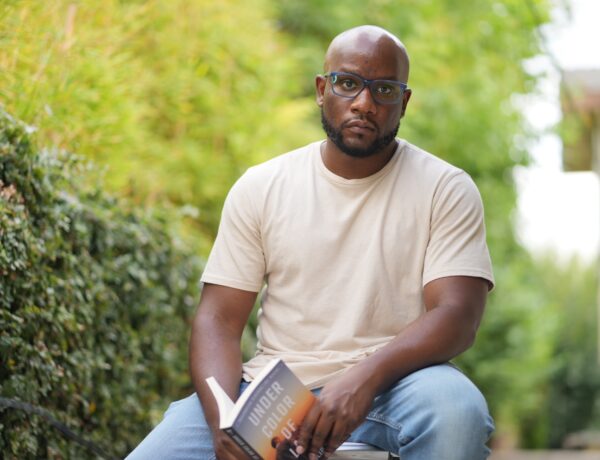

Jeff Pearlman is an American sports writer and author of nine books that have appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list: four about football, three on baseball and two about basketball.

Pearlman’s most notable works include The Bad Guys Won, a biography of the 1986 New York Mets, Love Me, Hate Me, an unauthorized biography of Barry Bonds, Boys Will Be Boys, on the 1990s Dallas Cowboys dynasty, The Rocket That Fell to Earth, a biography of Roger Clemens, Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s, The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson, and others.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Jeffrey! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. Can you tell us about your journey as a writer, from your early days at The Chieftain and The Review, to your current role as a New York Times best-selling author?

Back when I was growing up in Mahopac, N.Y., I wanted to write for the junior high school newspaper. However, my parents (rightly, I’d say) wouldn’t let me. My brother—who had difficulty making friends—was on the staff, and Mom and Dad thought he needed his own “thing.” His own space. Hence, the idea drifted out of my head, until my junior year at Mahopac High, when I started writing sports for The Chieftain.

I was—like most kids that age—a pretty awful writer. My first-ever published story was about the boys’ cross country team. Of which, in my first-ever journalistic conflict, I was a member. I only wrote a handful of articles, but something about the process worked for me. I liked seeing my name in print. I liked piecing the words together. I used to write the stories in a notebook, then go to school and use a computer.

As a senior, I was Chieftain’s sports editor. With the gig came my first signs of rebellion and obnoxiousness. At the end of the boys’ basketball season, I did a player-by-player report card of the team—and was called into the athletic director’s office for a dressing down.

During baseball season, I wrote a piece on how some members of the team thought the head coach—a legendary figure named Frank Miele, was too strict. Perhaps the most memorable story was a piece I did on Theresa McClure, a keyboardist for the school rock band, Illusion. I didn’t know Theresa, and she probably wasn’t all that great of a musician, but … well, she was cute. So I made up the excuse to interview her, wrote the story, then tried asking her out. She rejected me (unambiguously), and the other editors proceeded to repeatedly mock my efforts. It was warranted.

During my time writing Chieftain articles, I asked Joe Lombardi, the sports editor of a local weekly newspaper called The Putnam Trader, if I could do some writing that summer. He agreed—and my life was forever changed. Joe taught me stuff most 17-year-old aspiring writers didn’t know. How to craft ledes. How to work quotes. How to shift from one subject to another.

Joe was probably only 24 at the time, but he was smart and patient and understanding. He also let me write about pretty much everything—including profiles on most of my athlete friends and their college choices. I still recall my regular trips to the Trader office—the buzz, the excitement. I was hooked, like a crack addict, on writing.

I was an OK—but not amazing—high school student. I scored 1130 on my SATs, and decided I wanted to attend Penn State. Then I got accepted … to Penn State, Altoona Campus. Um, no. My next four choices—in no order—were Albany, Syracuse, UMass and Delaware. I visited UMass and hated it. Syracuse was a journalism haven, but crazy expensive. So it came down to Delaware or Albany. Albany or Delaware. I went back and forth.

Delaware was amazing, Albany was swell and less expensive. Finally, on the day I needed to decide, I went into my room to look over the brochures one last time. When I opened my desk drawer, only the Delaware pamphlet was present. Albany had vanished, which was strange, because I’d seen it there but an hour earlier.

It took it as a sign, and picked Delaware (years later I found the Albany informational packet. It had slipped behind the drawer and into a gap).

I was a gangly, pimply 18-year-old boy who had never kissed a girl. I had no game, no mojo. And yet, for some reason that eludes me, I was ridiculously overconfident about journalism. That summer, before my freshman year began, I had a requisite meeting with a woman who was designated my “student adviser.” (or something like that).

She had brown hair, and was young, and I told her I planned on coming to Delaware and, eventually, becoming editor of the student newspaper, The Review. I also told her I expected to write as a freshman—something that wasn’t allowed. She nodded politely, and told me it’s tough and hard and blah, blah, blah. I don’t think I was listening.

Well, lo and behold, my student adviser also happened to be the girlfriend of The Review’s outgoing editor. And, even before my first day, the staff had been warned about this cocky freshman asshole who believed himself to be the future of Delaware journalism.

Amazingly, I came to the office, showed them my Putnam Trader clips, and was permitted to write. But I was insufferable. Truly insufferable. I took editing like a child. How dare anyone change a word. Punctuation. Anything. I was great and they all sucked and I knew I was right. Dammit. Then, one day, I was approached by Josh Putterman, the paper’s managing sports editor. He asked that we sit down in The Scrounge, the nearby eatery. “The staff doesn’t want you writing for the paper any longer,” he told me. “They don’t like dealing with you.”

My heart sank. I was devastated. First thought: Transfer. Second thought: Transfer. Third thought: Apologize. The next day I wrote a lengthy letter and delivered it to Darren Powell, the executive editor. I told him I was wrong and stupid and ungrateful—and that I could change. He read it to the staff, and they decided to give me another chance. Thank goodness.

I went back to writing, and the guys at the sports desk—Dan. B. Levine and Alain Nana-Sinkam—were great. They handed me assignments, let me cover lacrosse as a beat. I’m not entirely sure why this subject caught my interest, but at the time I found myself wondering why Delaware and Delaware State never played one another in sports. Both schools were in the state, both were Division I-AA in football and Division I in everything else. And yet … nothing. I told Dan and Alain I wanted to give it a shot, and they let me. So I started talking to athletes from both schools. And coaches. Nobody, it seemed, knew what the Hens and Hornets didn’t play—but both sides seemed to want them to play. My money interview came with Edgar Johnson, the Delaware athletic director, who foolishly told me—on tape—that the game would be “divisive.” I wrote the story. It was heavily edited, and I uttered nary a peep. It ran across the top of the front page. Holy, holy, holy, holy shit—huge moment for me. Enormous.

Two weeks later, Delaware and Delaware State agreed to play in men’s basketball.

I had sort of arrived.

I returned to the Putnam Trader that summer, compiling more clips and building more confidence. I worked as a sports editor at The Review as a sophomore, and midway through the year I decided I needed an away-from-home summer internship. I applied to about 100 places, and received one offer.

For $5 per hour, the Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette would take me on as one of two sports interns. I was euphoric. My parents—being as supportive and giving as could be—allowed me to borrow the Chrysler. It was silver, and the power steering was broken. But, hey, a car’s a car. My mom and dad drove out with me. They also paid for my rent in a one-bedroom apartment at 405 East Green Street.

So what happened? Pure awfulness. To begin with:

- I had no friends. None. Zero.

- I broke my ankle playing basketball, was on crutches for several weeks, got off the crutches, returned to the court—and immediately sprained my other ankle.

- I’m pretty sure the guy in the apartment above me was beating his girlfriend. I had a TV that received two shows—Star Trek and The 700 Club. My mom bought me two plants to hang—I’m pretty certain they both died. I was so bored I tried taking up cigarette smoking … and failed miserably. Puff, cough, puff, cough.

- I was 20, and one needed to be 21 to enter bars.

Worst of all was the newspaper. Well, the worst of all was me at the newspaper. To be blunt, I was a little cocky fuckhead. I thought I was God’s gift to writing, and walked and wrote with an unwarranted strut. I took advice from no one, mocked older scribes, thought I had nothing to learn and no need to improve. In a word, I was insufferable.

The woman who hired me, a sports editor named Jean McDonnell, made my life even worse. She shredded my copy, told me what I needed to work on, demanded professionalism and (gasp!) told me I needed much improvement. With seven weeks in, I packed up and left. I was supposed to be there for eight but, hell, I couldn’t take it any longer. I was out. Ghost. See ya.

A few weeks later, I received a two-page letter from Jean. She told me I had talent, but that I wasted a great opportunity; that a bad attitude damns many a talented writer. I read the letter, probably cursed Jean out, and read it again. And again. And again. I still have it, stashed. It’s a prized possession.

And one that probably saved my career.

I returned to Delaware as a junior—cocky as ever, but with the Illinois experience a reminder that I was far from bulletproof. Midway through my junior year, I again applied for internships. I sent out about 150 applications. To here. To there. To everywhere.

That April, I got word from The Tennessean, Nashville’s daily newspaper, that I was a finalist for an internship in the features department. Patrick Connolly, one of the editors, called me and said, “To be honest, it’s up to a Vanderbilt student named Leah Stewart. She interned here last year, and if she wants to return we’ll take her. If she decides not to, you have the internship.”

I had, to be blunt, no other offers. Not one. I’d probably applied for, oh, 150 internships, and nobody showed any interest.

Hence, I waited for word on Leah Stewart.

And waited.

And waited.

And waited.

Finally, a few weeks later, Patrick called. “Leah’s decided not to intern here again. It’s yours, if you want it.”

I wanted it.

Nashville remains one of the great summers of my great life. There were five or six interns, and four of us were particularly close. We were housed in dorms at Tennessee State University—two to a room, no functioning air conditioning. My roommate was a news intern from Oakland named Reggie Payne. He doubled as a rapper, calling himself Sexy Sweat.

Reggie talked on the phone until 2 … 3 in the morning, which drove me crazy. But I loved the guy. His catchphrase was “Exxxxxaaaaaaaaccctly …” in a Cali-cool drawl. He wore a neon construction vest and, around his neck, a chain-link fence. In the adjacent room were the two other guys—Rick Jervis and Jared Lazarus, both of the University of Florida. Jared was a photo dude, Rick was a news writer. And, man, was he good. Like, really, really good. He had all these explosive clips, including one when he spent a day undercover as a homeless guy.

So, throughout the summer, Rick and I fancied ourselves as, oh, the Ali-Frazier of Tennessean interns. We battled for clips, counted who had more. We also went out—a lot. I was 21, and Nashville was a long way from Mahopac and Newark, Del. I had never been much of a drinker, and it wasn’t as if I was getting wasted every night in Music City, but, well, it was fun. My most memorable (actually, least memorable) night out came in July, when Rick, Jared and I hit a place called Ace’s Wild—a club with a DJ and a dance floor.

I remember meeting a woman who attended Michigan. I remember dancing with her. I remember drinking a lot. I remember, eh, nothing else. The next morning, Rick told me he was paged by the MC, and found me lying in a corner. He carried me to the car and brought me home.

As a senior, I was editor in chief of The Review. I’d accomplished what I’d told my adviser long ago—but it wasn’t easy. During my junior year, I still had many punk inclinations. The worst thing I did was quite awful: I’d written a lengthy feature about spending New Year’s Eve in Times Square, and an editor—Karen Levinson—sorta butchered it.

Such was her right—I was the writer, she was the editor. Still, I wasn’t having it. One day, before the issue went to print, I slipped into the newsroom and replaced her name with mine as the byline. This did not go over particularly well. The editor, Doug Donovan, actually demoted me.

Anyhow, I ran for the editor position against Adrienne Mand, a news editor and one of my best friends. We both had to give speeches, and I was ready. I wore a tie, I had a list of 100 things I’d do as editor. I just crushed it. Then—time for questions.The first hand up belonged to Karen Levinson. “If you’re an editor,” she asked, “would you be OK with people switching their bylines like you did?”

I knew this one would be coming—and I was ready. “Well, if I’m elected editor, I would hire competent editors to work for me, who know how to properly edit. So it wouldn’t be a problem.”

Karen Levinson was a decent person who tried her best. My reply was pure, 100-percent dickheadedness.

Somehow, I still won. I was as cocky as ever. I promised people the greatest newspaper ever—and I failed to deliver. It was sloppy and mistake-filled, but also adventurous and spontaneous. We had some amazing highs, and one terrible, terrible, terrible low.

There had been an alleged rape at the Pike fraternity, and the frat president (a guy I’m now good friends with) offered a quote. He said, “We still believe he is not guilty.” I was doing layout that night, and was tired. I used the quote as a headline, but accidentally wrote, “We still believe he is not innocent.” The paper came out, and I thought the president was going to punch me in the nose. Worst mistake I’d ever made.

Ever.

There was always someone telling me how awful the newspaper had become. A campus official. An advertiser. A parent. The president of the gay student union said we were homophobic. The president of the black student union said we were racist. Democrats thought we were too conservative. Conservatives thought we were too liberal. I’ll never forget one professor telling me, pointedly, that I’d led “the worst newspaper in my two decades at Delaware.” We released an April Fool’s issue that featured Snoop Dogg on the front page, beneath the headline Snoop Dogg Excited To Address Bitches At Commencement.

That was the article everyone talked about until I received a call from the Little People of America, threatening to picket outside our offices. Why? We ran another April Fool’s piece titled Midgets Fight To Take Over Newark. The accompanying photograph was of a short-statured former UD student, his head obscured by a football helmet. When his mom (who lived locally) saw the paper, she flipped.

That was not a fun call.

By mid-semester, I was probably averaging four hours of sleep per night. I was waiting for the next complaint, the next lawsuit, the next threat, the next … nightmare.

There was but one single saving grace: My staff. Twenty years later, I still love those people as if they were siblings. There was Adrienne, calm and cool and patient with my nonsense. There was Firm, the big-hearted feature editor. There was Faz, my dolphin sister, and Tollen—always convinced everything would be OK.

Garber was addicted to Snapple, Hickey owned hard news, Lew was the goofy freshman, Walter Eberz lived in the dark room, Lardaro took no shit, Dennis O’Brien was the hard-core military vet (RIP), Lauren Murphy was the hippie chick, Greg Orlando was the wrestling fanatic, Danielle Bernato famously covered a pro-choice rally, set aside her notepad and bellowed, “I’m Danielle and I’m pro-choice!” One writer covered a Matthew Sweet concert and hooked up with his guitarist. Another staffer liked popping people’s zits. Another always had his ass crack sticking out from his pants. On and on and on and on and on.

Two decades have vanished. I don’t miss the stress, or the long hours, or the struggle of putting out a paper. I don’t miss long deadlines, bad Scrounge food, fights with professors.

What I do miss, however, is the youthful innocence.

I miss the buzz.

During my senior year, I kept in touch with Sheila Jones, an executive assistant at The Tennessean. She told me I’d end up at the paper. Told me, told me, told me again. I wanted to believe her, but didn’t. So I started applying all over the place. Resumes, more resumes. One day I received a call from Catherine Mayhew, the new executive features editor of the paper. Would I come down for an interview?

I came down. We went to lunch.

I was hired.

My salary was $26,000. I was a food and fashion writer. Yes, I was a food and fashion writer. I immediately thought myself to be the hot shot. Twenty-two years old, straight out of college, hired by a major metropolitan newspaper to cover food and fashion for its features section. I could do no wrong. I was on my way.

Um, not quite. My first mistake was a big one. While reporting a story about a chef who cooked exotic meats, I asked—jokingly—whether he’d ever prepared human flesh (my sense of humor wasn’t exactly developed). He was not amused, calling my editor and demanding an explanation.

Shortly thereafter, I wrote a three-page profile of a local band, Dreaming In English, and identified the lead singer, Tyrone Banks, as Tyrone Brooks. Over and over and over again. The next week, I misspelled the winner of a local road race. I was asked to cover a Sheryl Crow concert and said she sang Viva Las Vegas, not Leaving Las Vegas. In an effort to stir up controversy, I penned an inane opinion piece calling Christian schools “stupid” for reciting prayers that included Jesus Christ’s name before basketball games.

When a news editor asked me to cover a murder, I went to the scene of the crime and, in an effort to get a good look at the damage, ignored the police tape and entered the apartment. When my editor wanted a piece on condoms, my lead was a graphic (and self-congratulatory!) description of my girlfriend and I having sex. On and on and on the mistakes went, one bigger than the other.

In the February 15, 1996 edition of the Nashville Scene, the city’s alternative weekly, a media critic named Henry Walker wrote, “If there is one cow-pie in the field, The Tennessean’s Jeff Pearlman will manage to step in it.”

He was 100 percent correct.

So what happened? I hit rock bottom. Fed up by the dizzying buffet of boneheaders, Mayhew had me switched to the police beat. For a month, she said, all we want you to do is focus on getting everything right. Names, dates, numbers, addresses. Don’t worry about writing—worry about reporting. Get the facts down, and everything else will follow.

It was the worst month of my life.

It was the best month of my life.

For most of those 20 or so days, the majority of my time was spent listening to a police scanner, then rushing out to crimes. There was nothing sexy or glamorous about being a cop writer. I interviewed police officers, took detailed notes, wrote straight leads leading into unoriginal formats.

It could be long, dry, dull, agonizing, yet it was exactly what I needed. I found myself surrounded by news writers, men and women who valued reporting chops significantly more than style and creativity. “Make sure you get the nuts and bolts right,” I heard more than once. “That way, the writing takes care of itself.”

I worked late nights, waiting for the big robbery, tragic fire, and the nearest murder. It was pretty dull stuff—every so often something happened. Mostly, though, my life consisted of writing 200-word briefs off of police releases. I wasn’t happy.

One day, however, Catherine came to me with gold. “How do you feel about tagging along with the police on an undercover prostitution sting?”

Uh … what?

Turns out the Nashville Police Department was troubled by the upswing in hookers, and wanted to get the word out that it was taking action. Hence, two days later I drove out to a fleabag motel in an awful part of town. I was introduced to Sue, the undercover female officer who was disguised as a whore.

I was introduced to Bob and Steve and Ed, the three officers positioned inside the motel room (where Sue would enter with the customer). Initially, I sat down in an across-the-street surveillance vehicle, where I watched the action on a monitor. After a while, someone said, “Do you wanna go in the motel room?”

Hell yes!

I’ll never forget the experience. I crouched down in a dark bathroom with the three officers. When we heard Sue enter the room (“C’mon, baby. Don’t be shy …”) we pounced! Wham! The looks on the faces of the men were priceless—and, oddly, heartbreaking. In a moment, their lives were forever changed.

Marriages—presumably over. Jobs—presumably gone. I’ve never solicited a prostitute or cheated on my spouse, but I certainly understand sexual urges. Not to that degree, but … well, yeah. It was sad.

One man, in particular, was crushing. His name was Richard Harrington. He was 34. When he opened his wallet, alongside his driver’s license was a photo of his wife and kids. “I’ve never done this before,” he said, shortly after offering $20 for oral sex. “Never.”

I was excited. Nervous. Sad. Energized. I rushed back to The Tennessean office to write my story. My editor, a nice man named Ted Power (not the ex-Reds reliever), asked if I had good stuff. “I do,” I said. “Definitely.”

After about an hour, I sent in the piece. Ted read it, in silence. He approached, tapped me on the shoulder and said, “We need to talk.”

Uh oh.

“Jeff,” he said, “I get what you’re trying here. I appreciate the effort. But we’re a family newspaper in the heart of the Bible Belt. You just can’t use this lede.”

“Why?” I said. “It’s true.”

“That’s fine,” Ted said. “But we’re not starting off a story with, ‘All Richard Harrington wanted was a blowjob.”

The Tennessean was a weird time in my life. Highs. Lows. Ups. Downs. I was lonely. My best friends were four or five African-American women at the paper, and they’d take me along to Nashville’s black clubs. It was wonderful and awkward at the same time. I once dated a woman who tossed her garbage out the window. That sorta stuff.

Although I’d always fancied myself a sports writer, I hadn’t been one since my junior year of college. At the conclusion of my cops beat stint, I was involved in a trade. The features department sent me to sports in exchange for Robin Hall, a young reporter who was tired of the grind. I was handed the highly coveted prep wrestling beat, and instructed by the managing sports editor, Neal Scarbrough, to own it. So I did. I made Tennessee high school wrestling my life. Got to know the coaches, the athletes … I tried to care about a sport I cared not one iota about.

Roughly eight months into my sports move, Neal offered me a sweet assignment. The University of Tennessee featured a junior quarterback from Louisiana … some kid named Peyton Manning. I was instructed to fly to New Orleans and find out everything about him. So I did. I tracked down teachers and coaches and friends and relatives. I even spent some time with this little kid … his brother, Eli. It was, until that point, the best story I’d ever written.

Throughout my time in Tennessee, my guiding dream was to one day write for Sports Illustrated. Why, when I was 13 or 14 I actually promised my mother that, eventually, I’d be an SI staffer. I’m not entirely sure why. Just felt it.

“It’s nice to have dreams,” she said, “but …”

But what?

“But you have to be realistic.”

You don’t understand, I told her. I WILL write for Sports Illustrated. I know it.

I probably first officially applied to the magazine, oh, a year into my Nashville stint. I wanted to do it right; to make an impression. Hence, I designed my cover letter to look exactly like one of those LETTER FROM THE EDITORs that occasionally appears up front. I used a photo of me, matched the font, and began the note with, “When Jeff Pearlman first applied for a job at Sports Illustrated way back in 1995 …”

Shortly thereafter, I received a relatively standard thanks-but-no-thanks note from Stefanie Krasnow, the magazine’s chief of reporters. She told me they had no openings, but that my letter was well received and, if I’d like, I could pitch some quirky story ideas for a now-defunct section known as advanced text (namely, pieces that, based on regional advertising, only ran in some of the magazines).

Stefanie didn’t have to ask twice. I sent in ideas, then more ideas, then more ideas. They were all rejected—too broad, too isolated, too this, too that. In short, I was thinking inside the box, not out of it.

Then—inspiration. Back when I was a sophomore at the University of Delaware, one of the editors at our student newspaper, The Review, had an idea. His name was Alain Nana-Sinkam, and he enjoyed a brief stint on the Blue Hens basketball team. Alain told us he wanted to apply for early entry into the NBA Draft, just to see what would transpire. I loved it! Alain loved it. Dan B. Levine, the sports editor, loved it! And yet … it never happened. Not sure why; just floated away.

So, a year later, I applied. I’d never played college hoops; just a single unremarkable track and cross country. I sent in the letter, announced I wanted to turn pro—and received calls from Rod Thorn and other NBA officials. It was great, and I wrote a brief piece for the student newspaper.

Now, three years later, I mentioned it to SI.

Bingo! Stefanie said it was on the money. So did other editors. I was paid, I believe, $1,500 to write my first SI byline but, of course, I would have done it for free. It remains a genuine highlight; seeing my name (my name!) inside Sports Illustrated. Actually, not just inside—atop a story! Shit! Wow! Me!

Shortly thereafter, Stefanie’s replacement, Jane Wulf, called and said there were openings in the bullpen (where the reporters worked). Would I be interested?

Would I?

She called again, a few weeks later, and offered me a position.

I sat in my den, in my apartment, and cried.

Then I called my mother.

That was 18 years ago.

That’s how it happened.

How did your experience working as a reporter and editor at different publications, like Sports Illustrated and Newsday, shape your writing style and approach?

I mean, I look back at my early stuff and it’s terrible. I was a cocky fuck, so I thought I could just write brilliantly and everyone would kneel at my brilliance. Turns out there’s a lot more to being a journalist than style points. It’s reporting, digging, making contacts, having sources trust you, confide in you.

Those are the lessons I learned at The Tennessean, SI and Newsday. Also, Sports Illustrated was a huge eye-opener for me, because all of a sudden I was surrounded by all these writers who were far, far, far superior. At some point many people go through that phase of thinking they’re amazing. And anyone who experiences that then has the bucket-of-cold-water moment where you realize you’re not particularly good and have a ton to learn.

The other thing I started to realize is 1,000 words is oftentimes better than 5,000 words. Economical writing is really hard, but almost always trims off all sorts of unnecessary fat.

Discover the daily writing habits of authors like Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Gillian Flynn with Famous Writing Routines Vol. 1 and learn how to take your writing to the next level. Grab your copy today!

Talk to us about your latest book, The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson. How inspired you to write about Bo Jackson and what was the process like putting it together?

He was a guy hanging up on my wall as a kid—and that always helps a candidate become a book. I’m very nostalgic, very drawn to my boyhood, very into taking folks I worshiped and dissecting them. Once I got the book deal from HarperCollins, I dove in hard.

My idea is to always build the world’s biggest subject library, so I spent a ton of weeks just acquiring every Bo Jackson writing I could find. I blow a lot of dough on ebay—media guides, biographies, etc. And I go day-by-day through Bo Jackson clips on newspapers.com. It’s a grind. Lastly, I interview everyone. Or at least I try to. I spoke with 720 people. It’s my favorite part of reporting, because you really learn about someone by talking to people who know him best. By the time it’s all done, I need a long nap.

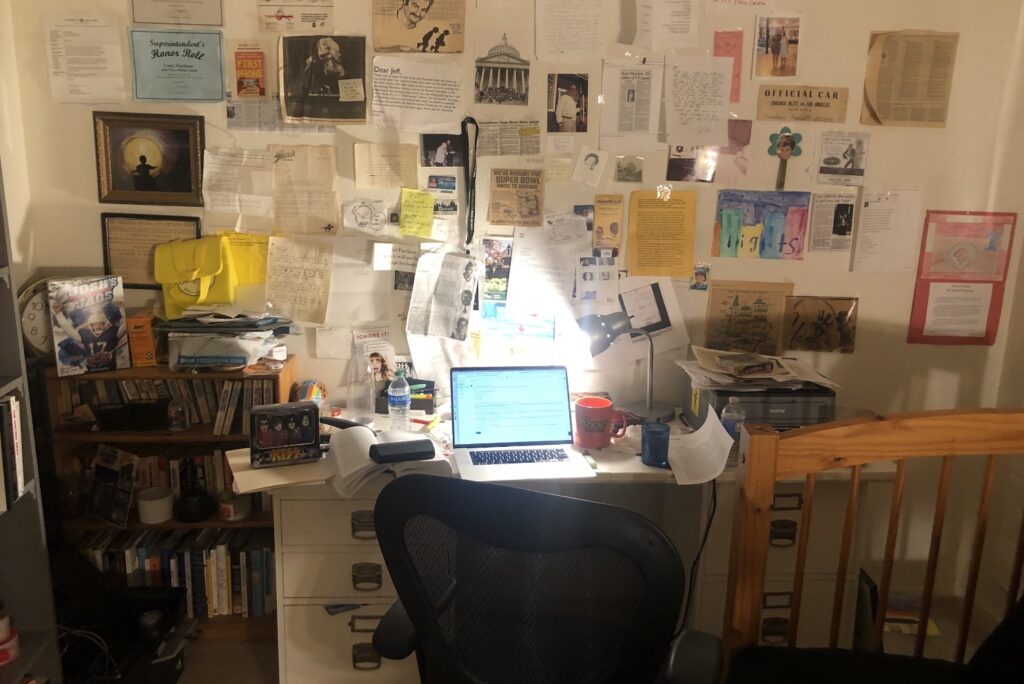

Can you speak to your writing process and daily habits? What does a typical writing day look like for you?

A lot of procrastinating, Xbox, googling “Emmanuel Lewis” and “horse fights gator.” When I’m writing, I try to do it in a coffee shop because I need the illusion of social interaction. So I pretty much know every cafe within 40 miles of my home in California. The main thing is to have a daily goal.

For me, when writing, it’s always clearing 1,000 words per day. Clear 1,000 and you accomplished something. I need that. A dangling carrot. Also, to be clear, this shit beats the snot out of me. Anyone who thinks writing gets easier with age is badly mistaken. I’m haunted all the time.

How do you keep yourself motivated and inspired when facing writer’s block or feeling uninspired?

I have two kids. They both need to eat. Plus, I love this shit. I really do. And the struggle is, oddly, part of the joy.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to break into the industry?

I’m 50. If you’re, oh, 22, your best route is to show me something I (a newspaper, a magazine, a website, a podcast) need that you (being young and spry) know about. I really mean that. It’s huge. Be the person who understands the next tik tok, and can tell a news outlet how to best use it.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments