Jazz Monroe is a journalist based in London, specializing in music and culture. He has been writing for Pitchfork for eight years and occasionally contributes to The Guardian.

His focus is on features and reviews, with notable projects including long-form features with Arctic Monkeys and Björk, as well as a deep dive into the Scott Walker album Tilt. He also works on the Pitchfork news desk.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

I’m a music and culture journalist based in London, primarily writing for Pitchfork and, occasionally, the Guardian. Most of my attention goes into features and reviews—my biggest projects last year were longish-form features with Arctic Monkeys and Björk, plus a deep dive into the Scott Walker album Tilt—but I also spend a lot of time on the Pitchfork news desk, where I have been on contract for eight years.

I’d love to learn about how you got into music writing. What initially drew you into the field, and what do you find most rewarding about it?

From roughly age 10 to 18, I did not learn to be sociable, funny, assertive or likable; life revolved around music, and the fuel for that was the press. I devoured NME—not necessarily the magazine as it came out, but ancient, fusty, broadsheet-sized copies unearthed from my local record shop in Norwich, in the east of England.

NME’s mid-2000s tone was aggressively down-to-earth, but I loved reading stylised older critics like Paul Morley and Steven Wells on bands like Joy Division or the Jesus Lizard, when those bands were new. Sections of those old magazines had plenty of dreadful, clueless, prejudicial rubbish, but there was a sense of writing as performance. I suppose that gave me an idea of how history is made, and a grasp of how what you’re living through now can come to seem fantastical later, partly through the written word.

When I started writing, I had a sort of mentor, a brilliantly unhinged wordsmith called Wendy Roby. She gave a guest talk at a music college where I was studying (I dropped out of regular school at 16). We only met a few times, but her attention gave me permission to try all this. She connected me with Andrzej Lukwoski, the reviews editor at Drowned in Sound, and then, from the age of 17, I wrote fortnightly-ish reviews clumsily in thrall to Wendy’s style, which was full of made-up words and unexpected images.

She had a charming, cartoonish fascination with music and its wonders. Emulating that felt creative, more like fiction than formal essay-writing, and it turned out to be a satisfying use for my teenage egomania. After that, Laura Snapes, who was then new on NME’s reviews desk, read my stuff and helped me get a foot in the door.

Your work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Guardian, The Independent, and Pitchfork, where you are an Associate Staff Writer. How does your approach to writing for different audiences vary?

Beyond checking my ideas are clear and images have just enough detail, I never think about readers while writing. But I read a lot, usually stories that are just a step removed from what I’m about to write. Planning a feature for the Guardian, I might not prick my pinboard with photos of disgruntled Labour Party members in nice scarves, but I will read so much Simon Hattenstone and Sophie Heawood that I’m thinking in their language, and I am in the unmistakable presence of Guardian Style.

I find Pitchfork less tonally even, which makes it exciting to write long there. The Sunday Review section in particular feels like a showcase of what music journalism can be: silly, funny, irreverent, enigmatic, tragic, sermonizing, poetic, full of high drama or throwaway one-liners—if it fits the record and the writer believes in it, all those can work.

I forget who said, of New Yorker style, that you’re not supposed to write it like that—at first it should sound like you, and if something is off, the subs put in the New Yorker voice. Whenever a writer like Amanda Petrusich squeezes a characterful, off-style gag into a piece, I want to high five them. You got it past the subs! That’s what it’s all about.

As a London-based writer, how do you think the city’s music scene has influenced your work? Are there any specific London-based artists or venues that have had a particularly big impact on your writing?

I grew up in a fairly dozy city—Norwich is wonderful but does not have an illustrious musical legacy—so reading about journalists’ gonzo-style exploits with bands, on the road or within their scene, was key to the allure of music. When I spend real time with an artist (Pitchfork and the Guardian usually negotiate a few hours in their home or creative space), I definitely want to glamourise their subcultures, alternative lifestyles and those places where the magic happens.

In terms of venues and artists, though, I don’t make regular appointments at any London spots—it’s pretty ad hoc. Some writers are more immersed in their scenes (shout out Kate Hutchinson) but my relationship with music has more to do with words than places. If I’m excited about a band, I’ll see them live. But when music gets me out of the house, it is nearly always to dance, and I don’t often write about that world.

Clubs like Corsica Studios and Dance Tunnel (R.I.P.) made me feel at home in London, and influenced me, personally, to an incalculable degree. It feels good to have those experiences stored away somewhere other than my work headspace. The memory doesn’t have to be verbalised.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

Can you tell us about your writing process? Do you have a specific routine or set of rituals that you follow when working on a piece?

As well as Hattenstone and Heawood, I tend to spend loads of prep time reading particular writers who will shape the piece I’m writing: Zadie Smith, Alex Ross, Geoff Dyer, Simon Reynolds and Wesley Morris are some. I use the Pomodoro Technique, and I’ll read Talk of the Town in the five-minute breaks, usually while snacking.

I’m convinced the most important work happens not in those gruelling writing sessions, but the mornings after, in bed. I’ll wake up, immediately read a page or two of a magazine to get into gear, and then go over the night’s work, making edits in my phone’s fiddly, unpredictable and torturously slow Google Docs app. In those couple of hours, in that cursed app, the work strikes me as perfectly clear, and often better than I’d imagined the previous night.

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

Being on the news desk during the week, I tend to write longer pieces on weekends. Saturday is part of the programme, but most of it is procrastination. I might finally start writing at 6 p.m., break for a late dinner, find an excuse to extend the break until the rest of the world is asleep, then write again until the early hours.

After the morning tinkering mentioned above, I’ll spend Sunday chaining coffees and teas and churning out what strikes me as unimaginative filler, just to get words on the page. This makes it sound like fast work, but since I don’t think in complete sentences, it often takes ten minutes to get to the end of one.

Even then it might have ellipses where words haven’t clicked. If the deadline allows it, I work slowly, and the work spreads across long days—that is a luxury, and curse, of living alone without any dependents.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers on developing a consistent and productive writing routine?

Avoid everything I just described! Set yourself artificial deadlines within the day and stick to them. Know how long the work takes you, and don’t delude yourself that this time will be quicker. Never have a drop of booze—unless, of course, you are transcribing your own interviews, when there may be no choice. Drink water and eat proper meals. If you must work late into the night, remember to eat late, lest your energy, and joie de vivre, elapse.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Most writers I like have uncannily similar routines: Write for four hours in the morning, and if the desk is calling, put in a couple more in the late evening. Honestly? I’d just like to have a conversation with someone whose routine is as chaotic, maddening and all-consuming as my own. If that person were Lydia Davis or Clarice Lispector, I’d be doubly happy.

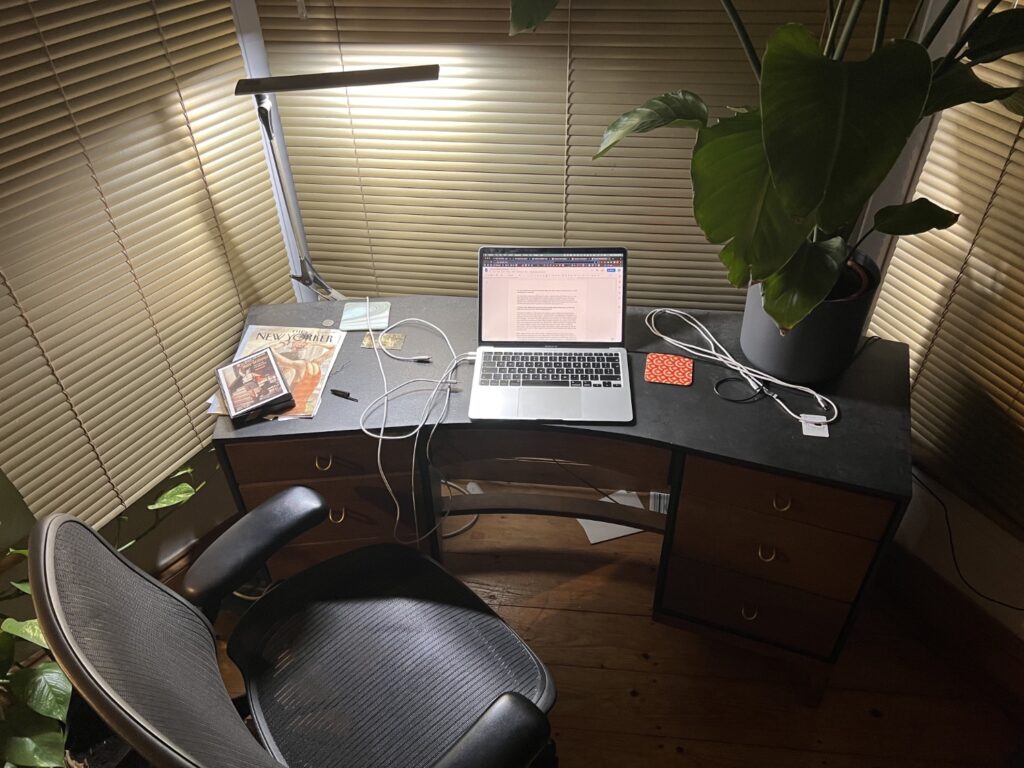

What does your current writing workspace look like?

It is a mysterious place. Clashing coasters. Necessary cables, then duplicates of those cables. A plant that was once small and cute but now faintly menacing, obviously belonging elsewhere. Nicknacks that have eluded my attention, often for months. There is a stack of postcards from a vintage film poster store in Mumbai. They are on the desk because, in theory, when conditions are ideal, I will use them to write long-overdue responses to friends I owe emails.

When I left them there forever ago, I suppose I imagined I would write the postcards that same day—ha ha ha. Under the cables on the right is something I could never possibly need: the template for a SIM card that was delivered last year. Why is it here? That is a question we may never be able to answer.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments