Barrett Swanson is a contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine. He was the recipient of a 2015 Pushcart Prize, and his short fiction and essays have been distinguished as notable in Best American Short Stories (2019), Best American Nonrequired Reading (2014), Best American Essays (2014, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2020 and 2021) and Best American Sports Writing (2017).

His work has appeared in many places, including Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, The Believer, American Short Fiction, The New Republic, The Atavist, Guernica, The Guardian, Best American Travel Writing 2018, and Best American Travel Writing 2020.

His debut essay collection, Lost in Summerland, was published by Counterpoint Press in May 2021. He and his wife live in the Midwest.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Barrett! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

Sure—and thank you for having me. I write essays, fiction and longform magazine pieces for places like Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, and GQ. Much of my magazine work involves embedding with zany or oft-ignored subcultures—manifesters, antiwar veterans, utopians, et cetera—and trying to understand how they might be synecdoches for larger trends within the culture.

My most recent longform assignment involved me staying at a “TikTok mansion” in Beverly Hills, where troupes of influencers room together and boisterously produce content for their millions of online followers. Later this year, I will publish two new essays, one about my attendance at something called “The Festival of the Ugly” in Piobbico, Italy and one about the five days I spent camping with the sober communities at Bonnaroo.

When I’m not engaged in these hair-raising expeditions, I’m a professor of creative writing at a small university in Wisconsin.

Your work has appeared in many prestigious publications such as Harper’s, The New Yorker, and The Paris Review. How do you approach submitting your work to different publications?

Um, with the typical fear and trembling?

I confess that I tend toward self-abnegation and ambient, low-wattage despair, so I’m usually pretty anxious when I send out a new submission. At the same time, I don’t really try to calibrate my sensibility to suit a specific venue.

In the past, when I’ve chameleoned my prose style to match whatever I took to be the aesthetic of a particular magazine, the experience ended up creating in me such seismic levels of shame and embarrassment that I can only look back upon such experiences with a kind of wincing resignation.

At this point in my career, I’m pretty much just exclusively interested in producing sentences that are both mindful of the reader and recreate, in language, the frequencies between my temples (and that hopefully can’t be mimicked by those language-processing algorithms).

This is what I try to teach my students—how to write sentences that only they themselves can produce. As hokey as this may sound, a sentence is, for me, the vessel through which one’s consciousness—one’s spirit—gets articulated, which is why I am so sedulously attentive to syntax and cadence and why my approach doesn’t really change regardless of the publication.

Lost In Summerland, your debut essay collection, was published by Counterpoint Press in May 2021. Can you take us through the process of putting together the collection and getting it published?

I assume you want me to skip over those moments of Sisyphean futility and head clutching desolation? Instead, a chipper summary: Sometime in 2019, I had produced about three-fourths of the essays that now appear in the collection, and I began to realize that there were certain ligatures between them, mostly having to do with stuff about how Americans were finding meaning in their lives in the absence of ideological commitment.

When I looked around, it seemed like a lot of my students and friends were sad and lost in ways that seemed both puncturing and all-pervasive, so I decided to devote the rest of the book to rigorously exploring those topics.

At that point, my agent, Samantha Shea, started sending out the manuscript, and eventually, my editor, Dan Smetanka, agreed to take on the project.

Your work has been selected for the Pushcart Prize Anthology and two editions of the Best American Travel Writing, and has received notable distinctions in Best American Short Stories, Best American Nonrequired Reading, and Best American Essays. How does it feel to have your work recognized in these prestigious anthologies and what sort of impact do you think it has had on your writing career?

Obviously, receiving distinctions like these is unutterably gratifying, and they make you feel cherished and worthwhile and validated, et cetera, but one thing I have learned as I get older is that these goal posts keep moving—that it’s easy to fall prey to the samsara of achievement.

I confess that as a young writer I labored under the mistake of believing that getting published in this or that magazine—or receiving this or that award—would essentially amount to some existential accreditation, where I would finally feel like I had “made it” as a writer and where some approximation of the love and comfort I felt in utero would be swiftly returned to me or whatever.

The sad fact is that when you do win an award or receive a distinction, you (or I, anyway) end up feeling good for exactly three minutes, and once the neurochemical sizzle of happiness wears off, you remember that you still have love handles and are slow to respond to texts; that you didn’t do enough research before the last midterm elections; that sometimes you still drink from disposable plastic bottles; that you need to call your parents; and that, oh yeah, see that blank page over there, you still have to contend with that.

In other words, I try not to measure my worth as a writer by these yardsticks, if only because I’ve learned the hard way that their pleasures are mostly transient. No distinction will erase your foibles and blemishes. No award will alleviate the torsions inside your head.

Can you walk us through your daily writing routine, from when you start to when you finish?

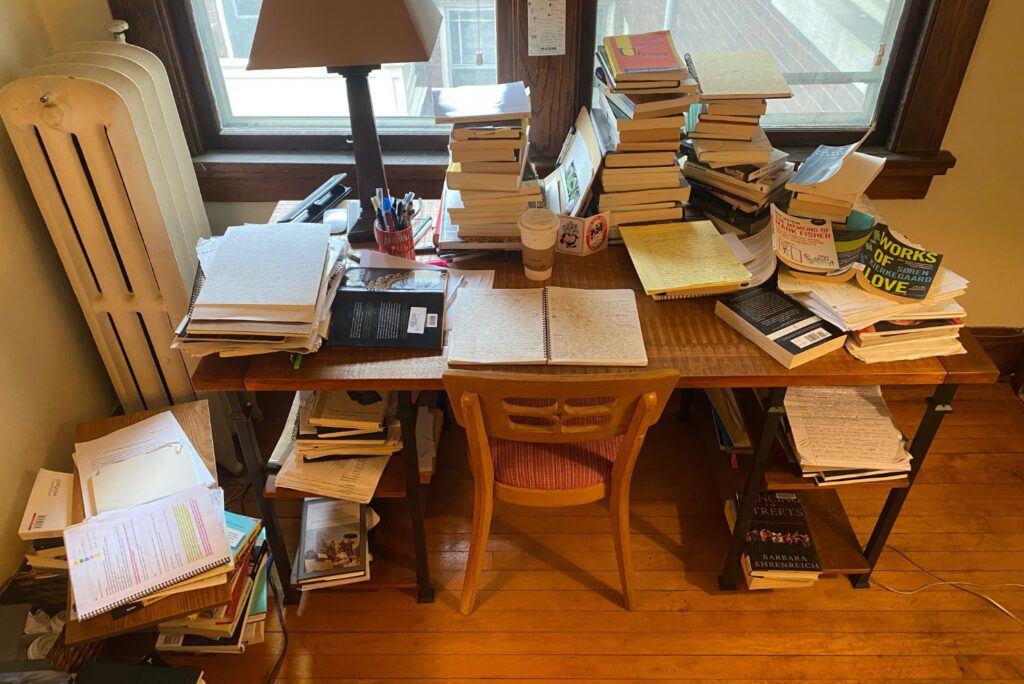

I usually wake up and start writing roughly at 5AM. It’s only at such an ungodly hour that I can muffle the Greek chorus of self-laceration just long enough to be productive. I write first drafts longhand because it allows me to better hear the cadences of the sentences.

I usually stop sometime around 10AM, at which point I head to campus. I recognize there’s nothing sexy or idiosyncratic about this—no exotic Yankee Candles, no ambient Gregorian chants. Instead, it’s pretty bare bones around here. Just Bic pens and brass tacks.

How do you handle writer’s block and maintain inspiration for your writing?

I don’t really experience “writer’s block,” per se. It’s more so the case that every so often I will stop writing for a couple of weeks, if only to let myself be more meaningfully engaged with the exigencies of day-to-day living.

I try to read and experience more in those breaks, try to spend more time with my colleagues and family and friends. To be released from the imperatives of narrative during those periods is weirdly replenishing and tends to have the paradoxical effect of actually improving my writing.

Do you have a set goal for the amount of words or pages you aim to write each day?

God, no. For me, such quotas are too distressingly similar to the sad metrics of tracking your exercise and “counting your steps” that I just can’t do it. I just try to write good sentences. Even a handful of them each day can be counted as a victory.

What does your writing workspace look like?

Like a room that’s been recently burglarized. Like the economist John Nash’s office in that movie A Beautiful Mind. Here’s a pic:

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments