Charlotte Mandell is a French literary translator who was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1968. She went to Boston Latin High School, the Université de Paris III, and Bard College, where she majored in French literature and film theory.

In April 2021 she received the honor of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her husband, the poet Robert Kelly.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Charlotte, really great to have you here with us today, I’m super interested in your work as a translator. For those who may not know, can you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

Thank you for inviting me! It’s an honor to be here. I’ve been a literary translator for thirty years, and have translated over forty books, including works by Maurice Blanchot, Jean-Luc Nancy, Paul Preciado, Jonathan Littell, and Mathias Énard. My translation of Compass by Mathias Énard was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize and received the National Translation Award in 2018. I recently received the honor of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government.

You’re currently in the process of translating Marcel Proust’s In the Shadow of Young Women in Flower. Can you talk about how a project like this starts off and the various hurdles you encounter along the way? Forgive my ignorance but I can’t imagine it to be as straightforward as just translating the words on the page.

Proust’s sentences are intricate and complex, and they can include many subordinate clauses and digressions. The challenge for me is to follow his syntax as closely as possible, so that we see the thought process behind the construction of the sentences, how one thing follows another. Proust is famous for his ability to show, in writing, how a person thinks; I know no other author who can dissect a single thought, a single memory, so accurately and thoroughly, with such insight and sensitivity.

My challenge as a translator is to try to follow Proust’s own way of thinking as closely and faithfully as possible, with as few distractions and interpolations as possible. I want the sentences to speak for themselves—I don’t want to add anything or take anything away. It’s definitely a challenge to try to be as simple as possible while conveying an incredibly complex thought or idea.

One of the things that makes Proust’s intricate, lengthy sentences a little easier to follow in French is the existence of gendered nouns in French. It seems such a simple thing—une pomme (an apple, feminine), un jour (a day, masculine), but when that noun is followed by an adjective which has to agree with the noun, it makes it easier for a French reader to know which adjectives go with which nouns.

Since we lack gendered nouns in English, it can be difficult to make the referent clear, especially since a predicate can come quite late in a Proustian sentence, when one has already forgotten the subject. There are ways to work around this confusion (repeat the subject, or, if absolutely necessary, change the syntax around so the adjective is closer to the noun), but it is a challenge.

What does a typical work day look like for you?

I’m more of an evening person than a morning person, so I usually get to bed late and rise late—I wish it were otherwise—I love mornings and wish I could enjoy them more. So I’ll have a late breakfast/ brunch and then I’ll go for a walk (we live in a beautiful part of the Hudson Valley, near Bard College).

I’ll start work in the late afternoon after my walk, and will work at my desk (upstairs, looking out onto beech and locust trees, and a little triangular park) until dinner. I sometimes listen to classical music as I work—I used to listen to bel canto operas, Bellini, Rossini, Donizetti—or to piano sonatas by Bach or Beethoven—but lately, with Proust, I find I need to work in silence, to concentrate on his sentences. If I listen to anything while I’m translating Proust, it would be Bach’s The Art of Fugue, which is sort of the musical equivalent of Proust’s sentences.

Do you have a target word count or number of pages that you like to translate each day?

It depends on the book—with an ordinary novel, I try to do at least ten pages a day, sometimes more—I tend not to work very quickly. With Proust, I do much less –maybe 1500 words a day, four pages or so. Each sentence takes so long!

What would you say has been the most enjoyable translation experience to date?

I loved translating Mathias Énard’s 500-page, one-sentence novel Zone. It takes place on a train from Milan to Rome (the number of pages, 513, is the same as the number of kilometers between the two cities), and it has the same sort of propulsive, energetic rhythm as a fast train does. Since there are no periods, there’s no obvious stopping-place, so I had to force myself to stop translating at the end of the day before I got too tired.

I entered a sort of trance-like state as I was translating it, from which it was hard to emerge at the end of the day. Also, I make it a principle never to read ahead, so that the text I’m translating is always fresh and exciting; in the case of Zone, I kept wanting to find out what happened next. I miss that experience. I also loved translating Énard’s Compass, which, although it does have sentences, is written in the same sort of stream-of-consciousness narrative.

If you could give just one piece of advice to someone trying to get into the translation field, what would it be?

Read as much as you can, in any language you know (and in some you don’t). A translator, like an author, is a prism of everything they’ve ever read; our language is shaped by the language of others, just as we ourselves are shaped by others. And then (sorry, two pieces of advice): Find an author who isn’t well known, and who hasn’t been translated into your language yet; read as much by that author as you can, translate a favorite passage, and send the excerpt out to various magazines and publishers. It helps to be passionate about the work you’re translating.

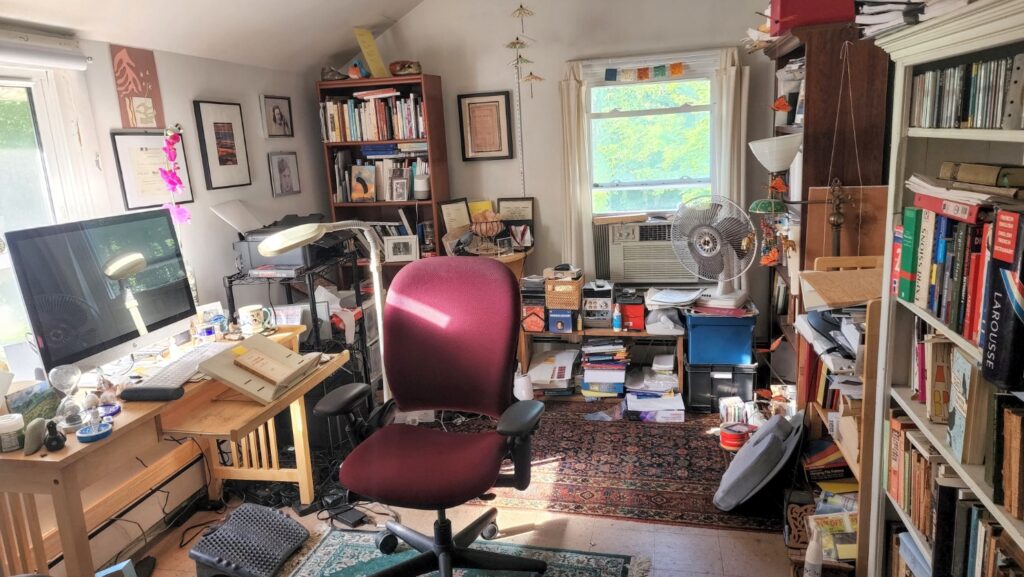

What does your translating workspace look like?

It’s not very big, and a little more cluttered than I’d like it to be—I tend to collect things (rocks and shells, mostly), so in my case more is definitely more. It has two windows—one facing east, the other north—so it gets a lot of light. There’s a bookcase full of French books (mostly fiction and poetry), another with reference books and my complete set of Le Grand Robert (a very good French dictionary), and another with all the books I’ve translated, alongside my translations. Also a lot of CDs, which I don’t play much anymore. And some photos of my mother, Betty Reid, on the ranch in Colorado where she grew up; of my father, Marvin Mandell, when he was a soldier in the army during WWII; of our friend William Weaver, the great translator of Italian, given to me after he died by a cousin of his; and of my husband, the poet Robert Kelly.

Before you go…

Each week, we spend hours upon hours researching and writing about famous authors and their daily writing routines. It’s a lot of work, but we do it out of our love for books and learning about these authors’ creative process, and we certainly don’t expect anything in return. However, if you’re enjoying these profiles each week, and would like to send something our way, feel free to buy us a coffee!

No Comments