Edgar Gomez is a Florida-born writer with roots in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico. A graduate of University of California, Riverside’s MFA program, they are a recipient of the 2019 Marcia McQuern Award for nonfiction.

Their words have appeared in Poets & Writers, Narratively, Catapult, Lithub, The Rumpus, and elsewhere online and in print. Their memoir, High-Risk Homosexual, was called a “breath of fresh air” by The New York Times, recognized as a Stonewall Honor Book, and named a Best Book of 2022 by Publisher’s Weekly, Buzzfeed, and Electric Literature. They live in New York and Puerto Rico.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Edgar, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, we’re so glad to have you here with us today! You were born in Florida with roots in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico. How has your background influenced your writing and what role does your heritage play in your work?

My background influences the stories I feel the most urgent calling to tell (whether about machismo in Nicaragua, queerness in Orlando, or colonization in Puerto Rico), and the word choices I use to tell those stories (Spanish speakers/Southern people have sayings for everything, queer folks have our own references we pull from, etc.).

I used to have a fear that my background would limit me in the publishing industry and American publishers would reject my work for being too “niche.” It’s a valid worry and it does happen, however, the types of stories and art I enjoy most are, in fact, “niche.” There’s nothing wrong with being particular, or showcasing hyper-specific voices and unique situations.

As much as I can, I try to disconnect myself from my capitalistic impulses to mold my writing into what will sell and be most appealing to publishers, and instead trust that there are readers out there who will respond to me being myself.

Your writing often tackles themes of identity, sexuality, and community. How do you approach these sensitive and personal topics in your work?

Very slowly. When I first began to write, I was in such a rush. Chasing the high of getting stories published. Finishing a draft and sending it right out. Trying to get paid and have money for rent. Maybe that’s okay if you’re writing fiction, but with memoir and personal essays, the responsibility you hold to both yourself and to the people you’re writing about is… different.

The real-life consequences are higher. I try to give myself at least three months if I’m writing a story that deals with something sensitive. I like to sit with what I’ve written for a while and give myself the chance to change my mind. Something major can happen in three months that alters your perception completely. One day you might think a memory is traumatic, the next you could remember an absurd detail that makes you laugh at the same scene, a month later you might find a comfortable medium between the two.

Then there are questions that memoirists should always ask themselves: Am I being generous? Am I being vengeful? Have I done my due diligence? What are my motives for telling this? All of this takes time.

Your writing has appeared in various outlets including Poets & Writers, Narratively, and The Rumpus, among others. How do you determine which pieces to share in which outlets? How do you choose the right home for your writing?

It really depends on the story. There are some that are so personal, that I am so attached to and so unwilling to revise to meet a specific, perhaps higher paying magazine’s editorial eye, that I am okay with publishing it somewhere that gives me next-to-nothing if it means that I’ll get to maintain my authentic voice. I try not to make money my number one priority, though it’s very hard because, well, capitalism!

High-Risk Homosexual received a lot of recognition and praise from various publications, including The New York Times. What does this recognition mean to you as an author?

It’s been both shocking and not shocking, to be honest. Shocking, because I know what the statistics look like—books like mine aren’t often published, much less praised by those big publications. And shocking because I remember where I started, as a queer, Latinx kid who couldn’t even afford to go to the library sometimes because gas cost too much money for my mom to take me.

But it’s also not shocking to me, because I work very hard at writing, and because I’ve had to build up an immense reserve of confidence—I think almost all writers do; the odds are so low that any book will succeed, you have to believe in yourself. You have to believe you’ll make it. I’m grateful for any recognition, but the recognition that matters to me most is from queer readers. They’re the ones who never doubted me, and to whom I feel most indebted to.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

Being named a Stonewall Honor Book is a significant achievement for any LGBTQ+ author. Can you share your thoughts on the importance of representation and visibility for the LGBTQ+ community in literature?

Representation can be an important tool for the imagination. If you can’t see something, if you’re not sure it exists, then it can be difficult to imagine it for yourself, right? For me, one of my biggest insecurities around publishing was that I didn’t see many writers like me out there, and so I didn’t know if publishing a book would be possible for me.

Now that I do know it’s possible, I hope that shows other writers their stories are valuable and that there is a way. At the same time, representation can be tricky. We have to be critical of visibility. Queer people have always been around; perhaps now other people are learning about us more, but I had a whole life and community before any outlet spot lit me.

Many outlets, regardless of how unbiased they would like to appear, have agendas, whether they’re selling papers or shaping larger cultural conversations. It’s important to look at who they’re spotlighting and ask why, and who they’re excluding. I’m very hesitant to use my visibility to say, “I made it, so you can too!” because that’s a slippery slope towards tokenism. What does it mean to make it? According to whose standards? This is why recognition from other queer folks means the world to me.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

When I was in graduate school, I had a professor give me the advice that if I wanted writing to be my job, then I had to start treating it like my job. There are hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of people who want to be writers, people who are waiting for someone to tell them, “Okay, you’re a writer!” But no one is going to tell you that. You have to just do it. So, before I received a cent for my writing, that’s what I did. It’s simple and it’s not simple: you have to decide you are a writer and then you have to go do it.

That said, I don’t have a set writing schedule. My basic philosophy is: write as much as I can, wherever I can, and if I’m not writing, then I’m reading, and if I can’t do either, then I’m cleaning, so that there will be fewer distractions around me when I’m ready to sit down. As of late, I write about five or six days a week. If I’m busy, I’ll try to get in at least an hour in, even if it’s broken up into fifteen-minute chunks. If I have more time, I’ll go an entire day—from around noon to 10PM.

That’s because I’m under some tight deadlines at the moment. But I also make sure to give myself plenty of breaks. A week where I won’t write anything at all, or where I’ll just poke around in a story and revise. As a memoirist, it’s important to give yourself space to be a human in the world and make new experiences, otherwise you’ll stop growing.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

That would be Zora Neale Hurston. She had such style and determination and confidence in herself as an artist. I remember reading that when she lived in Harlem, she would host parties for figures of the Harlem Renaissance, and oftentimes while the parties were still going, she’d go into her room to write. I’d like to know more about that—about her passion and drive.

But I think what I would like to ask her the most about is money. She didn’t earn nearly what she deserved, and in fact she died penniless. From letters she wrote, it sounds like she anticipated that might happen. I’m interested in the ways artists find happiness outside of capitalism, what motivated her when she was afraid of things like paying rent, whether she was ever bogged down by things like that. Essentially: what made it worth it for her.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

I’m currently reading a Spanish translation of a book by Mieko Kawakami titled Pechos y Huevos. Before that, I read Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, All This Could be Different by Sarah Thankam Mathews, and Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams—all of which I really liked.

Right now, because what I’m writing about is poverty, I’m enjoying books that talk about money in a way that isn’t totally sad or totally funny (which can feel deflective). Books that make room for both, that offer me new perspectives about money and how to live in a world that is ruled by it. I’m here for anything that speaks of mutual aid, community, care work, and navigating systems of oppression. Also gay shit.

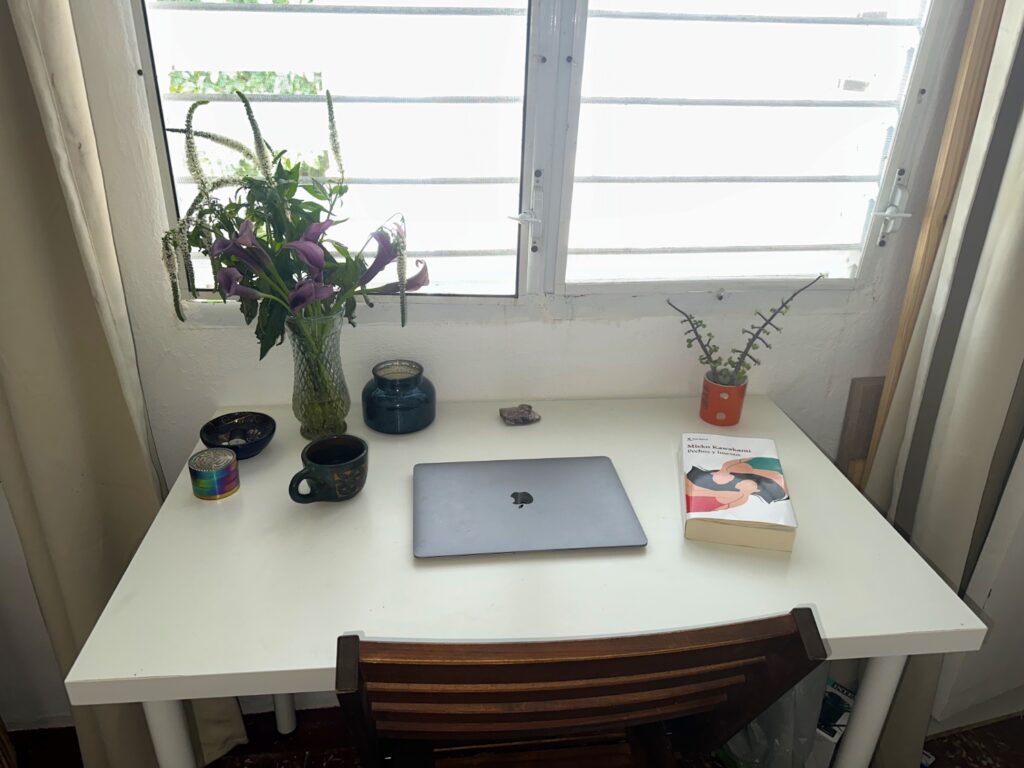

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I don’t have a stable writing space right now in Puerto Rico, where I’m currently living. Sometimes I write from bed, which I don’t love because I get sleepy. Sometimes I write from an Ikea desk my landlady is letting me borrow. In general, because writing can be so static, and because I get FOMO from people I see on social media having fun outside, I try to make it as fun an experience for myself as possible.

I’ll make coffee, light a candle and put out flowers or a precious stone, and dress up cute. I’m not a sweatpants writer. Wearing my good clothes helps me feel more connected to the world, instead of like a hermit who spends all day crouched over my laptop.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments