Exclusive premium content for members only! Already part of the club? Log in here. Still on the fence? Become a member for only $50 USD a year here.

Ready to dive deep into literary genius?

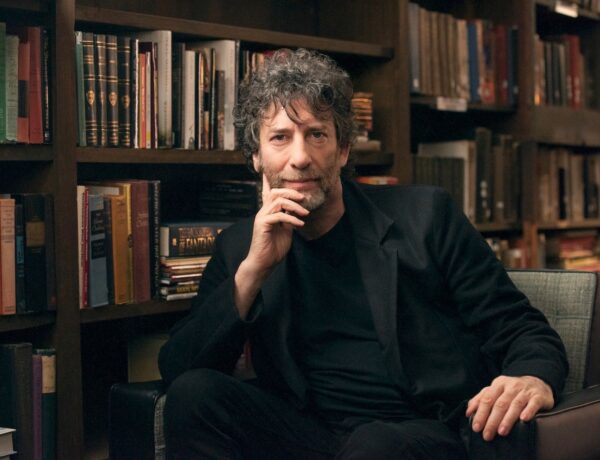

Every writer has a ritual. A sacred dance of habits that unlocks the imagination, teases out stories, and paves the path to masterpieces. What if you could uncover the exact routines that guided Ernest Hemingway or Maya Angelou? How about understanding what drives modern luminaries like Neil Gaiman or Gillian Flynn?

With the Famous Writing Routines premium membership, you don’t have to wonder anymore. For just $50 USD/year, you gain exclusive access to:

🖋 The daily rituals of literary titans such as Stephen King, Salman Rushdie, and Toni Morrison.

📚 Behind-the-scenes peeks into the habits of contemporary best-sellers like Marlon James, Laila Lalami, and Ocean Vuong.

📖 Understand the discipline and drive that fuel the works of award-winners like Kazuo Ishiguro and Elizabeth Gilbert.

This isn’t just a list. It’s a curated collection that takes you on a journey into the lives of writers—from the classics to the modern, from mystery weavers like Elmore Leonard to poetic souls like Amanda Gorman.

Become a part of an exclusive community that believes in the power of routines. Let the legends and their habits inspire your next chapter. Let’s face it; we all need that extra nudge, that secret sauce, that ‘aha’ moment. And this? This might just be yours.

Why wait? Elevate your writing journey and unlock the secrets of the greats. Secure your premium spot with Famous Writing Routines today! 📖✨