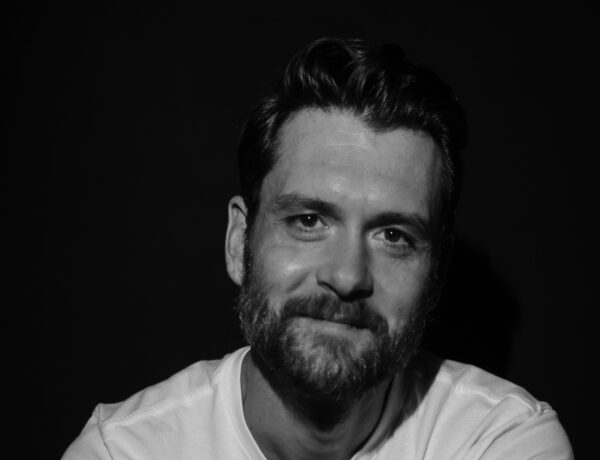

Simmons Buntin is a multifaceted professional known for his roles as editor, writer, publisher, and educator. He founded Terrain.org in 1997 and serves as its editor-in-chief, also heading Terrain Publishing as its director and president.

Buntin co-edited the anthology Dear America: Letters of Hope, Habitat, Defiance, and Democracy and authored Unsprawl: Remixing Spaces as Places. His poetic works, published by Ireland’s Salmon Poetry, include Bloom and Riverfall. His first collection of essays, Satellite: Fatherhood and Home, Near and Far, will be published by Trinity University Press in early 2025. He has contributed to various literary and scientific publications and occasionally teaches at the University of Arizona Poetry Center.

Hi Simmons, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, great to have you here with us today! Can you tell us about how Terrain.org came to be and what inspired you to create the world’s first place-based online literary magazine?

Thank you for having me! I founded Terrain.org with Todd Ziebarth as we finished up our graduate program in urban and regional planning at the University of Colorado at Denver in 1997. We wanted to do something unique—bring together both literary and technical work in a single, place-based magazine.

So: poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction, as well as articles, community case studies, and interviews, plus artwork, all in a beautiful package. We used Orion as a model—a magazine I still greatly admire—and at first hoped to create a new print magazine. But we had neither publishing experience nor funding, so we opted for a low-cost model at what was the dawn of the internet: an online magazine, or e-zine. We’ve grown considerably since then, but at our core have remained focused on place, as well as climate and justice, while remaining advertisement-free and free to access—keeping, we hope, beauty and equity at the forefront.

With a background in both urban planning and creative writing, how do you see these two fields intersecting in your work?

My writing today—whether poetry or prose—is seeded in my view of the world as someone trained in urban planning, and particularly someone who advocates for walkable, livable communities. Come to think of it, that’s the basis for Terrain.org, too—the nexus between the built and natural environments where it exists, and a discourse where it does not.

Other themes in my writing (and existence) are central, as well—fatherhood and photography, for example—but it all comes down to community and the places we build to foster community, or, alternatively, how we reshape places to enhance community. And here I think of not just the human community, but the other beings—as the wonderful writer CMarie Fuhrman calls them—in addition to human beings: plants, animals, landscape.

I’ve just finished a book of essays publishing in 2025 titled Satellite: Fatherhood and Home, Near and Far, and in just about all of the essays, community based on good urban design and the principles of sustainability is central—even in one of my favorites, which at first blush wouldn’t seem related because it’s a kind of personal history of craft-brewed beer. And yet, beer may be why humans gathered and formed communities in the first place. But I’ll leave that as a teaser for you to read the full essay once the book is out…

You have a strong connection to place, and your book Unsprawl examines the ways in which our communities have been built over the last half-century. Can you tell us about some of the visionary strategies discussed in the book for introducing new patterns of development?

You bet. Unsprawl: Remixing Spaces as Places grew out of the Unsprawl community case studies series in Terrain.org. These communities are both new and renewed—greenfield, grayfield, and in-fill—but what’s critical for each is that pedestrians are given priority over cars.

So primary services—shops, restaurants, parks, healthcare, places of worship, community centers—are in close proximity to each other. If these services are not within a ten- or fifteen-minute walk then they are easily and safely accessible via public transit. That also means that the neighborhoods don’t segregate land uses as has happened across suburban North America since the 1950s.

Residences may be above retail on narrow streets with wide sidewalks and bump outs for restaurant patios. Small neighborhood schools are set within neighborhoods rather than pushed to the exterior. Perhaps there’s a town center that serves as park and civic and event space. The idea is to make our neighborhoods more humane: more beautiful, safer, healthier, greener, constructed from local materials and designed using traditional, regional architectural styles.

They have a sense of place—you know whether you are in Tucson or Tacoma or Topeka based both on landscaping and building design. The case studies also highlight measures to save energy and water, such as solar photovoltaics, reclaimed water systems, natural wastewater treatment, providing employment onsite so less gas is used for commuting, and the like. The good thing is that most if not all of these measures can be applied to existing communities, providing a template for retrofits that make them more livable, more equitable, more economically viable, and—in a warming world—more resilient.

The thirteen projects in the book—including the gorgeous community of Civano in southeastern Tucson, where I lived for eighteen years—are not without their challenges, or their flaws. So the book includes lessons learned for each. In many cases these communities were designed not just to be great places to live and work, but also to serve as pilot projects to determine if their innovations work.

So in Civano, an array of building materials were used, from recycled steel framing to straw bale to a Styrofoam-concrete mix to rammed earth (in one custom home, anyway) to foam-filled block. Which were cost-effective? Which were energy-efficient? Which were easiest to build with? These outcomes matter if the goal is to take the lessons learned and apply them more broadly. And that must be our goal if we want to build and rebuild more sustainable communities.

In your opinion, what is the most pressing challenge facing the planning, design, and development of communities today?

I think the most pressing immediate challenge for planning, design, and development (or redevelopment) is access, and I don’t mean that from a transit perspective, although that’s related. I mean access as it relates to equity, which is to say equal opportunities for everyone to have access to affordable housing, to clean water, to clean air, to healthy food, to safety and security, to nature—regardless of their income or race or sexual orientation or level of physical or mental ability or any other attribute for which so many people have been unfairly and usually en masse marginalized.

Longer term—and it’s not that far out there—the most pressing challenge is radically reducing the amount of nonrenewable, carbon-based energy we use in manufacturing, building, living, and moving, because reducing our energy use reduces pollution and greenhouse gas emissions which slows the very serious impacts of what writer Alison Hawthorne Deming calls “climate weirding”—consequences we are currently experiencing daily: wildfire, flooding, desertification, rising sea levels, more severe storms, the drying of rivers and reservoirs, and so on.

Those are all systemic changes, but systems start locally, and that’s why innovative planning, design, and development initiatives like those undertaken in the Unsprawl book and in countless communities across the world matter. Bit by bit, and if we’re persistent, cog by cog, they change the system.

Your most recent project, Dear America, is a collection of letters focused on hope, habitat, defiance, and democracy. Can you tell us about the process of putting this book together and what you hope readers will take away from it?

Terrain.org strikes again! Dear America is an anthology published in partnership with Trinity University Press that grew from Terrain.org’s Letter to America series, which began just after the 2016 U.S. presidential election with a letter by Alison Hawthorne Deming. Once I read that letter, I knew we needed to canvas as many writers, artists, scientists, and thinkers to submit their own letters.

For the next several months, we only published these letters—poems, essays, and artwork—setting aside all other contributions. We published nearly 260 letters through the run of the series, which ended in 2022. Dear America collects 85 of these letters, often revised, and adds 50 more new letters from such writers as Robin Wall Kimmerer, Jericho Brown, and Rick Bass.

For the book itself, working with Trinity University Press we knew we needed to include new work not currently available online, but—once our proposal was accepted—we also worked on an abbreviated timeline, because we wanted to get the book out on the 50th anniversary of Earth Day (April 22, 2020). And who knew a pandemic was coming at that time?!

I worked closely with co-editors Elizabeth Dodd, Terrain.org’s nonfiction editor, and Derek Sheffield, Terrain.org’s poetry editor, to solicit contributors, select from those letters we’d already published, and create book sections both surprising and compelling. What normally would take 18 months was accomplished in less than half that time because there was a unique urgency around not just the Earth Day deadline but also the upcoming 2020 presidential election campaign season.

The results of the 2016 presidential election, and the turmoil of the four years of the president following his inauguration, present an imminently teachable “moment” in U.S. history. For progressives and those who support true democracy, those were dark days. (I recognize well that before the election many in America were already under dark days.) What can and have we learned? What could or should our response be? How could we maintain hope? How can we maintain hope even today, when so much of the hate- and fear-based rhetoric and actions of that period continue, if the recent laws passed by many state legislatures are any indication?

The answers to these questions—or more aptly put, the pursuits of those answers—are what I hope readers get out of this book. To quote Deming’s original letter, “Think of the great spirit of inventiveness the Earth calls forth after each major disturbance it suffers. Be artful, inventive, and just, my friends, but do not be silent.” This book is about not being silent. It also happens to be a great resource for teachers, something we support through talking points, lessons, and other resources here.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

My writing routine is to not have a writing routine. I long ago learned that I’m a deadline writer—for prose, at least—and so I often work backwards from a deadline, starting with what I hope is enough time to finish. That’s probably why I was so productive in grad school—I had an essay due every three or four weeks, so I’d get it done.

Without a deadline, however, and with the very real constraints of editing Terrain.org plus a full-time job and family and dog-walking and the occasional road trip and the like, writing doesn’t often just take the back seat, it lives in the trunk. And for many years—a decade, really—that’s where my routine and writing lived: the dark and vacant trunk.

Over the last 18 months, however, I’ve returned to writing to finish my essay collection, and have sequestered minutes and sometimes hours here and there to write. In that time, I finished my first two full essays in more than ten years—and 7,400-word and 8000-word pieces at that! What was my routine for that one?

Getting used to writing on my laptop in the living room, headphones in, while my family was together over the holidays. And spending twenty minutes revising before work. And some evenings working way too late into the night when the muse was with me—though I certainly can’t do that like I once did. Most recently, I wrote on a free evening in a hotel room in Seattle, and then pulled out my laptop and wrote for two and a half hours on the return flight to Tucson (a first for me). I was also fortunate enough to spend a week at the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in the Cascade Mountains of central Oregon this summer, where in addition to exploring and speaking with researchers, I did a whole lot of writing on the final essay of the collection.

So for me, there is no “typical day” when it comes to writing, but on any day that has writing, it more likely than not occurs in the evening—after work, after dinner, after Wordle—or on the weekend, when I should be taking a hike or doing chores or working on Terrain.org.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

As a writer of creative nonfiction, could I really pick anyone other than Michel de Montaigne? A close second may be Bill Watterson, author and illustrator of Calvin & Hobbes. Hold on, I’d better add Virginia Woolf and Emily Dickinson to that list, too. And James Baldwin. And Mark Twain. And a whisky with Ernest Hemingway.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

I just finished Sonia Shah’s The Next Great Migration and it was terrific. I had not before thought about how we are all invasive species. Fascinating, and rich in human and natural history. Photographer Dave Showalter’s Living River: The Promise of the Mighty Colorado, which I also just finished, is much more than a coffee table photography book, though it’s about that size. Chock full of watershed maps, interviews, and discussions on the future of the river and so the West in an age of climate change, it’s required reading (and viewing) for any Westerner.

I’m also reading the new anthology Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, edited by Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, and Derek Sheffield. I’ve been a cheerleader for the regional literary field guides that have been published here and there—Sonoran Desert, Southern Appalachia—but this one is a masterpiece. Whether you have an affinity with the Pacific Northwest or not, you need this beautiful book. Finally, I’ll be spending some time with Anne Haven McDonnell’s poetry collection Breath on a Coal this weekend. We’ve published several of her poems in Terrain.org, and if those are any indication, this is going to be a powerful, poignant collection.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

If you see it from Zoom, where I host many of Terrain.org’s monthly online readings, it looks like a closet. But in fact it’s a neat little built-in corner writing desk in our den/guest bedroom/workout room. My window looks out to the east, to our back patio and a somewhat misfit citrus tree, where occasionally I’ll see a hummingbird or mockingbird or, in the evening, watch the swollen moon rise over the Rincon Mountains (or a sliver of them, anyway).

But more and more I’m training myself to write in our living room with the laptop resting on my legs, feet up on the ottoman, the fireplace and its impressively realistic LED fire to my left, our rescue dog snuggled like the sofa seal she is on the cushion to my right. Which is where I am right now, signing off before I take her out into the cool spring evening one more time before bed, the grapefruit tree blossoms a dizzying, aromatic delight.

No Comments