Sheila Liming is a professor at Champlain College in Burlington, Vermont where she teaches literature, media, and writing.

She is the author of two books, What a Library Means to a Woman and Office, and the editor of a new edition of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. Her essays have appeared in notable publications such as The Atlantic, McSweeney’s, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She is also active on social media platforms such as Twitter and Mastodon. Her latest book is Hanging Out: The Radical Power of Killing Time.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Sheila, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, great to have you here with us today! Your latest book, Hanging Out: The Radical Power of Killing Time, explores the importance of unstructured social time as a key element of our cultural vitality. What inspired you to write about this topic?

To put it bluntly, I’m interested in tracking the decline of things—spaces, institutions, practices—that were once thought of as being crucial to human life and culture. My first book was about libraries; my second book was about offices; my third book, Hanging Out, is about the waning of both a social practice (spending unstructured time in the company of others) and the spaces that support and give rise to it.

At the same time, it’s also about the changes that have been wrought to hanging out. These days, we do a lot less hanging out in person but we do plenty of it in a virtual, highly mediated way, through the internet and similar mobile technologies.

I became interested in thinking about what hanging out had been, back before those technologies affected such drastic changes, and also what it must be, now, moving forward. I was inspired by the observation that, as we age, certain factors conspire to make hanging out less possible. I wanted to write a book that would inspire others, in turn, to reclaim some of those basic social practices.

Can you share more about the concept of hanging out, and why you believe it is a crucial aspect of our social lives?

Hanging out is, as I see it, an endangered species of activity. But it wasn’t just the COVID-19 pandemic that made it so; it was already getting hard to hang out before COVID came along and made it even harder. That difficulty stems from the way that modern life is built around isolation, self-reliance, and the demands of personal productivity.

Sherry Turkle wrote about this phenomenon over a decade ago in her book Alone Together, and since then, the situation that she described has only grown worse. I styled my book Hanging Out as a manifesto because I wanted to encourage people to reclaim the behaviors and practices that they had given up, perhaps without even noticing that they were doing so.

At heart, I believe that hanging out is central to the work of mutual coexistence within a democratic society. We have to be willing to engage with each other, to share space with each other, and to spend time in each others’ company — three things that digital technology once promised to make easier but, today, succeeds in making it more difficult. We are lonelier than ever, in part because we have been taught to equate loneliness with privilege and success.

How has technology and the digital age affected our ability to hang out, and what can we do to counteract those effects?

It’s no secret that hanging out has become harder because of the internet. But it has also become easier, and that’s part of the paradox of hanging out in a post-internet world. Digital technology—especially personal mobile devices like smartphones—makes it easy for us to locate willing or sympathetic audiences.

That’s a good thing, in part, because it allows us greater freedom in engineering the systems of support that will sustain us. But it’s a bad thing, too, because it has the effect of decreasing our stamina for unpleasant, confrontational, awkward, or even just boring encounters. There is always another choice that can be made and another audience that lies elsewhere.

As a result, we grow more impatient with the work of hanging out with each other in person, in real, face-to-face environments, which are less subject to control than the curated spaces of the internet. In order to counteract those effects, we have to get good with discomfort and develop a tolerance for situations that are less than ideal, perhaps, but more real. That includes sharing space with others, including strangers, and remembering what it means to exist in a world where not everything can be quit, controlled, chosen, or unchosen via the swipe of a finger.

What a Library Means to a Woman explores the connection between libraries and self-making in late 19th and early 20th century American culture. What drew you to examine this topic, and what were some of the most interesting findings from your research?

I love libraries, and I love spending time in libraries. In the summer of 2015, I got a grant to begin work digitizing the personal library collection of the American writer Edith Wharton, which is held at The Mount, her historic home in Massachusetts. The digitization project allowed me to spend a lot of time both in Wharton’s library, inhabiting the space of it, and with Wharton’s library, meaning interacting with the books themselves.

From both types of interactions, stories started to grow – some mine, some belonging to others. The desire to communicate and tell those stories became What a Library Means to a Woman, which is less about Edith Wharton than it is about libraries, in general, as technologies of self-making. Some of the more fascinating findings that resulted from my research related to the value of the library collection, which was a subject of fierce debate.

I studied internal documents that had been prepared in connection with The Mount’s purchase of the library collection. Three separate appraisals, for instance, were conducted in order to secure a purchase price, and each appraisal turned out to be wildly different. What I learned from this is that evaluation of historical library collections is not a science and it remains highly subjective, based on a kind of sentimental calculus that accounts for the associations of the original owner and the motivations of contemporary buyers and sellers.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

You mention Edith Wharton’s library and its connection to her literary persona. Can you share more about Wharton’s library and its significance to her self-making?

Wharton had a great fondness for libraries and believed that her success as a writer was in part based on her exposure to them, which began at a young age. In her autobiographies, she portrays her parents as being largely uninterested in books and dismissive of authors as a class, yet it’s clear from her own library that her parents gave her many volumes, forming the seed of her own personal library collection. One thing that Wharton’s library thus helps to make clear is the depth of Wharton’s own investment in the myth of her supposed “self-making.”

What is your own relationship with libraries, and how have they influenced your own personal and professional journey as a writer?

Attached to my car keys, I have three mini keychain library cards. There are three of them because I have moved three times in the last three years—from Grand Forks, North Dakota (Grand Forks Public Library) to Burlington, Vermont (Fletcher Free Library) to Essex Junction, Vermont (Brownell Memorial Library)—and, with each move, I’ve been loath to part with the most recent library even as I’ve been eager to start a relationship with the next.

I was raised by libraries. I wouldn’t be the person I am today without them, and I certainly wouldn’t be the writer that I am today. In Hanging Out, I pay tribute to this idea in the introduction, explaining that “This book is partially about me but it is also about the larger world that I inhabit. I am speaking, in an ecosystemic sense, of a world of other people, other voices, other stories and other books.

I cannot write without these other influences by my side, urging me on; but what’s more, I cannot, in an ethical sense, imagine a world in which writing without them would be viewed as acceptable or permissible. Insofar as hanging out describes a process that unfolds in group settings and so is necessarily shared, writing, for me, constitutes a kind of hanging out with the ideas and books and writers, both living and dead, who have shaped my thinking.”

As an associate professor at Champlain College in Burlington, Vermont, how do you balance your teaching responsibilities with your writing and research pursuits?

I save my big writing projects for summer, because I teach a lot (4 classes per semester) during the school year. Meanwhile, I try to accomplish a lot of “legwork” related to my writing projects during the regular semester—by which I mean things like writing pitches and proposals, following up with contacts, conducting preliminary research, advanced reading, etc.

I also write shorter articles and essays during the school year and, sometimes, those provide the foundation for bigger projects. For instance, Hanging Out partially grew out of an essay about literary parties that I wrote for a magazine called Majuscule. It was while writing that essay that I started thinking more seriously about the various forms of hanging out and how they’re represented in literature.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

I wrote the entirety of Hanging Out during the summer of 2022. I was on a deadline at the time and knew I didn’t have much wiggle room, so I adopted a pretty structured writing routine to keep me on task. For the first month, I wrote a chapter a week: I would start at about 7:30 a.m. every morning (because that’s when my partner leaves the house for work) and I work write until about noon, at which point I would take a break and either go for a run, a walk, or head to the gym.

I like to use exercise as a kind of punctuation that both breaks up my writing routine and also creates time for further thought and reflection. While I’m running, or hiking, or walking, or on the rowing machine at the gym, I’m thinking about what I just wrote and what I’m going to write next. Then, by the time I sit down again to write, later that afternoon, I usually have a plan and am able to just charge forward once again.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

There are simply too many to choose from! But I’m quite obsessed with the writer (and illustrator, and artist) Tove Jannsson, who I talk a bit about in Hanging Out. From reading her correspondence, I’ve gathered that Jansson was a fascinating person who took a very disciplined approach to her artistic practice.

We see some of that discipline reflected, I think, in some of her fiction, like the novels Fair Play and The True Deceiver, both of which provide metacommentary on the work of producing art. I would love to sit down with Jansson and listen to her talk about topics like discipline, routine, building good habits, fighting bad ones, and making friends and enemies through art.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

I’m usually reading about 4-5 books at a time. They sort of fit into categories: 1-2 books that I’m re-reading because I’m teaching them, plus something hard, plus something softer and more desert-like.

Right now, the books that fall into those categories include: Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and Edith Wharton’s short story collections Ghosts (both re-reads), Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici and a new translation of Stendhal’s epic The Red and the Black (both rather “hard”), and Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You? (that’s the “dessert”). I recently finished reading Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer (sort of between “hard” and “dessert”) and Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These (pure dessert).

Can you describe what your writing workspace looks like?

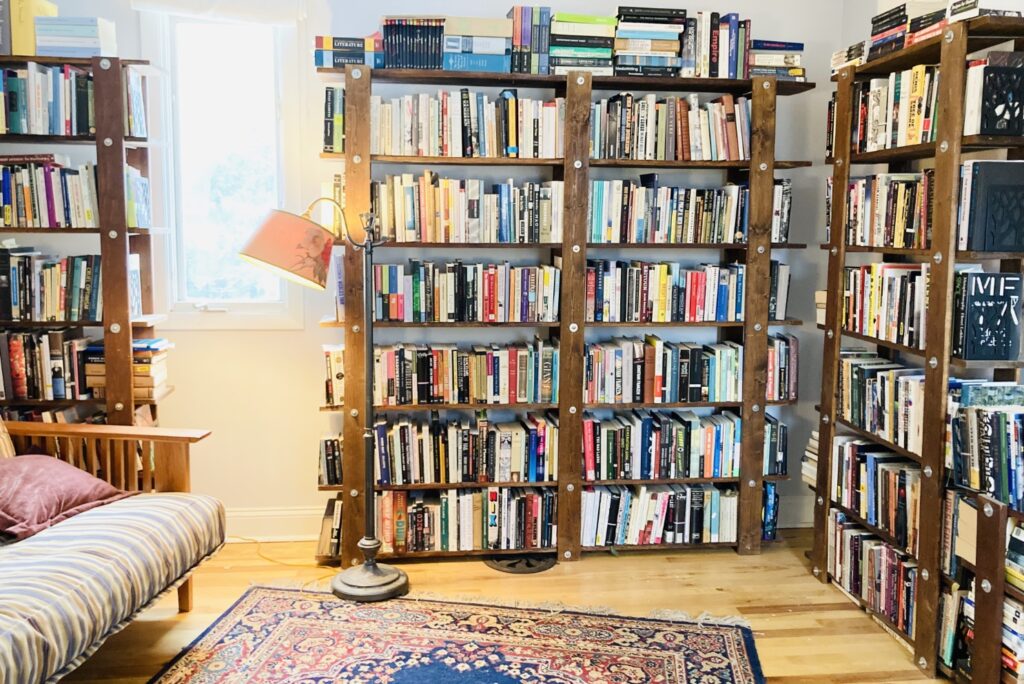

I moved into a new house 18 months ago and have yet to make my office there what I want it to be. But it is functional, in that it houses my desk and about 70% of my books, which I need to have around me when I’m writing.

The problem is that I’ve long since run out of shelf space and the books have started to pile up – on the futon that I keep in my office (not for naps, since I never nap, but in case I have out-of-town guests who need to use it), on the floor, on my desk, etc. Every piece of furniture to be found in my home office is second-hand.

For instance, I actually found the desk while I was on a lunchtime walk around my neighborhood, back when I lived in a more urban and densely populated section of Burlington. I had just been complaining to my partner about needing a desk when I saw one sitting there on the curb with a “free” side on it.

Together, we picked it up and hauled it back with us, and I screamed “Thank you!” in the direction of the house that it had been parked in front of, just in case the inhabitants who had thought to give it away were still within earshot. It felt like a gift from the gods. Meanwhile, the futon came from Craigslist and the bookshelves—which I built myself—came from scrap wood and this wonderful set of free instructions.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments