Richard Beard’s six novels include Lazarus is Dead, Dry Bones and Damascus, which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. In the UK he has been shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award and longlisted for the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award. His latest novel Acts of the Assassins was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and he is the author of four books of narrative non-fiction.

His 2017 memoir The Day That Went Missing won the 2018 PEN/Ackerley Award for literary autobiography, and was shortlisted for the Folio Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. In the USA the book was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Formerly Director of The National Academy of Writing in London, he has been a Visiting Professor at the University of Tokyo and a Creative Writing Fellow at the University of East Anglia. In 2017 he was a juror for Canada’s Scotiabank Giller Prize and in 2019 is a judge for the BBC National Short Story Award.

Hi Richard, thanks for being with us today! You have worked in a variety of professions, from P.E. teacher to an employee of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. How have these experiences contributed to your writing?

Writing can only ever be a part-time job – I had to live some life. I’m therefore grateful for these experiences, however much I didn’t want to do them at the time. I wanted to be writing. But if I’d only been writing I’d have had nothing to write about, and so on.

Your memoir The Day That Went Missing won the 2018 PEN/Ackerley Award for literary autobiography, and was shortlisted for the Folio Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. In the book, you describe an act of collective denial in your family’s reaction to the drowning of your brother Nicholas. How did you navigate the complexities of writing about such a traumatic event?

I started from a position of total forgetfulness about that traumatic event in my family’s life. We explicitly blocked out the day. In that sense, it was easy to get started on the book, because the denial meant I didn’t feel emotional about turning over a few stones. At least at first. Deliberately numb to the emotional impact, I could start to rediscover what actually happened by framing it as a forensic detective investigation – I went back over the documents left behind and interviewed people who were there. Gradually, I realised that this approach was another form of emotional denial. My body let me know it was time to let the emotion in. And once that happened, the book changed. It was flooded with emotion, which was true to my experience while writing it.

You were a juror for Canada’s Scotiabank Giller Prize and are a judge for the BBC National Short Story Award. What do you look for in a winning book or story?

In those two examples the judges are reading more than a hundred novels or over a hundred short stories. The pieces of writing most likely to reach the shortlist therefore have to stand out in some way. They have to be outstanding. This requirement tends to favour stories with a distinctive voice, even a brash voice, and many prize-winners have this, which sometimes I feel is a bit unfair. Quieter stories or those with more subtle effects or a more enduring impact can miss out. Anyone entering a writing competition needs to remember luck plays a part. Judging, I’ve seen that luck up close – the result depends on the make-up of the jury, or maybe there’s an over-represented theme or subject. This might be the year every writer turns in their best writing.

You are also an occasional contributor to several publications, including The Guardian and The Financial Times. How does writing for different audiences and formats differ from writing a novel or memoir?

I love a constraint, and therefore I’m always happy to fit my writing to word-counts and specific briefs. I love questions like these ones, for example. With a novel I’m out on my own, in the middle of an ocean, waiting for the wind.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

I don’t have a typical day but I have a process with recognisable stages. I start by reading and procrastinating. I have a large plain notebook – useful sentences from my reading I copy into the front of the book and fresh ‘original’ ideas go in the back. In the second stage I fill these sentences from the front and back of the notebook into whatever structure I’ve devised for the book. Each chapter or section is therefore like a box to be filled in. This initial writing stage allows me to produce (badly-written) pages, with which I can now start a dialogue. The third stage is by far the longest and most intense and best suited to the idea of a ‘day’s work’. This is the editing and rewriting. I print, edit the hard copy with a pencil, type the edits back onto the computer, print again. Repeat. I like to pile up the physical drafts under my desk to see the height of work I’ve done.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Shakespeare! I recently visited his schoolroom in Stratford-upon-Avon, and couldn’t help wondering how he did it. How did he get from that half-timbered, half-remembered building to King Lear?

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favourite recent reads?

Last year was the summer of Proust, which just as he could have told me (in six volumes) was an unforgettable experience. I’ve got myself up-to-date with the excellent Slough House spy series by Mick Herron and have become a devoted fan of Annie Ernaux. I admired the ghost-writing of Spare to such an extent I’m now reading J.R.Moehringer’s Open by Andre Agassi, but these are Moehringer’s books. Maybe one day his will be the name on the cover.

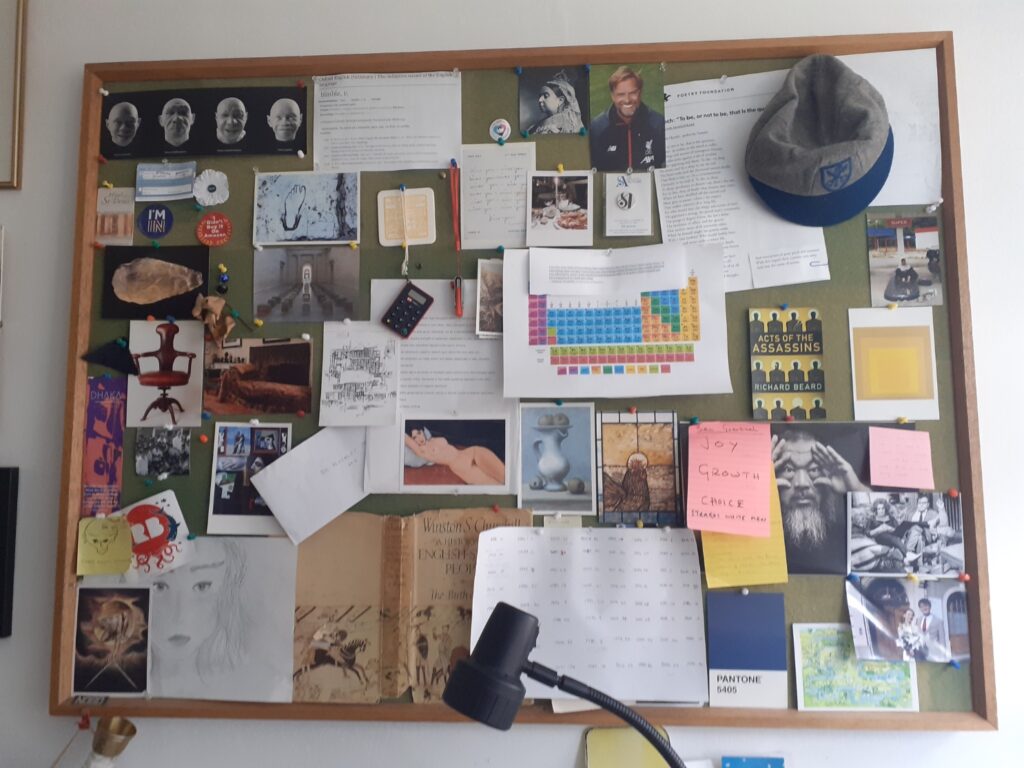

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I’ve recently finished a book so I’ve tidied up! A tidy desk is boring, so this is my pin-board above the desk.

No Comments