Melissa L. Sevigny is a nonfiction author and science reporter who grew up in Tucson, Arizona, where she developed a deep love for the natural world and all things southwestern.

Her writing explores the connection between science, nature, and history, and has appeared in various publications including Orion, The Atavist Magazine, and River Teeth. Melissa is the author of Brave the Wild River (W.W. Norton, 2023), Mythical River (University of Iowa Press, 2016), and Under Desert Skies (University of Arizona Press, 2016), and her work has been recognized with numerous awards and grants from organizations such as the Ellen Meloy Fund for Desert Writers and the Arizona Commission on the Arts.

As a science communicator, Sevigny has covered topics ranging from planetary science to sustainable agriculture, and was a member of the team behind NASA’s Phoenix Mars Scout Mission in 2008. She holds a B.S. in Environmental Science & Policy from the University of Arizona and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing and Environment from Iowa State University.

She is the science reporter at KNAU (Arizona Public Radio), where her radio stories have been nationally recognized and have aired on NPR and Science Friday. In her free time, she volunteers as the interviews editor for Terrain.org and is a member of the National Association of Science Writers.

Hi Melissa! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

I’m the author of three nonfiction books, most recently Brave the Wild River (W.W. Norton, May 2023). I write about science and nature, really in any format I can—books, essays, radio journalism, a bit of poetry. My bachelor’s degree was in environmental science, but I added so many creative writing classes along the way that I ended up with a double major.

I blended my love of science and of words by getting an MFA in Creative Writing and Environment from Iowa State University. Now, I live in Flagstaff, Arizona, where I work as a science journalist for the local NPR station. I also volunteer as the interviews editor for Terrain.org, the nation’s oldest place-based online journal. In whatever time I have left, I like to garden and hike.

Your work often explores the intersections of science, nature, and history in the American Southwest. Can you talk about what draws you to this particular region and the stories it holds?

I was born here. I grew up in a house built by my grandfather on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona, and spent all my childhood in the Sonoran Desert. My mother took my sisters and I on camping trips—the Santa Rita Mountains, the Black River, the Grand Canyon—and those are still the places that have a hold on my heart. It’s a rich region for story: full of history, diverse cultures and peoples, and some of the strangest plants and animals you’ll ever lay eyes on.

You have experience working in fields such as planetary science, western water policy, and sustainable agriculture, how do you incorporate these diverse perspectives into your writing?

I always intended to be a geologist, and what derailed that plan was the realization that I could never pick just one thing to study. I’m fascinated by all aspects of science, but particularly those that touch on the natural world.

Working on a NASA Mars mission directly led to my first book, Under Desert Skies, and my time at a water policy research center turned into Mythical River. I like taking ideas and conversations that are locked away in academic circles or obscure scientific journals and bringing them into a space where more people can engage. One way to do that is with metaphor, dramatic action, and other techniques of storytelling.

My approach to telling science stories has changed over the last decade or so. As my research skills have improved, I’ve gotten better at finding characters who have been hidden or overlooked; I’m particularly interested in female scientists. That led me to write Brave the Wild River, which recovers a forgotten story about two botanists and their epic adventure on the Colorado River.

Can you walk us through your research and writing process for your latest book, Brave the Wild River?

Brave the Wild River is the true story of two botanists, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter, who rafted the Grand Canyon in 1938. It’s based on unpublished diaries and other documents housed at various archives around the country. I had big plans to visit all those archives and line up all my research very neatly before diving in—which all went out the window when the pandemic began.

In an odd twist, I think this turned out for the best. It meant I had to start writing with the documents I had copied before the country locked down, which were Clover and Jotter’s diaries and letters. My first draft ended up being very strongly rooted in their voices and experiences. I eventually made it to the archives and got to see documents written by the men of the 1938 river expedition, but the story had taken shape by then, in the best way possible: with the women at the forefront.

My writing and research process tends to be physical. I like to print out drafts as I’m working, cut them up, and move the pieces around. I used to do this on the living room floor, until my husband got tired of it and built me an epic, 24-foot-long sliding bulletin board.

I enjoy archival research and love digging through obscure scraps of paper for hidden gems. I also interviewed a lot of people—scientists, historians, descendants of my main characters. But there was another bit of research I needed to do that was far outside my comfort zone: I had to raft the Grand Canyon. I’d never gone on a river trip of any kind, let alone a two-week whitewater rafting trip. I joined a botany crew in the fall of 2021 and kept a detailed diary. Later, I typed up fragments and incorporated them—at first literally, with Scotch tape—into my draft. The book has a lot more texture, color, and sound because of my experiences on that trip.

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

I write on Saturdays. This sounds simple, but it’s a cardinal rule for me: I wake up, go straight to my computer, and write—before I do anything else, before coffee, even. My best writing often comes in that liminal space when I’m not quite awake, when my anxieties and insecurities aren’t yet clamoring for attention. I write for as long as I can—on a good day, this might be eight or ten hours.

On a bad day, I might get in just one or two hours, and then I’ll get up, take a walk in the woods, wash dishes, or do something else physical and repetitive until I feel ready to get back to work. “Writing” for me isn’t just putting words down, but also research, reading, editing, organizing—but I stay away from email and fiercely protect my writing time.

The important thing about this schedule is that it gives me permission to not write the rest of the week. Back when I tried to follow the “write every day” advice, I tied myself into knots, because it just didn’t work for me. I work a full-time job Monday through Friday, and do my best to rest on Sundays.

Of course, if I’m under a deadline I’ll squeeze more writing time into my schedule, and I’ll write under uncomfortable circumstances if I must—while waiting for an oil change at Jiffy Lube, for example—but the weekly pattern grounds me. I find my mind continues to tug at little problems all during the week, and I’m fresh and ready to work when Saturday comes.

Your work has been recognized with numerous awards and grants, including the Ellen Meloy Fund for Desert Writers and the Arizona Commission on the Arts. How has this support impacted your writing and career?

Tremendously. The Ellen Meloy Grant was, I think, three thousand dollars at the time, and I used the money in part to travel to Dinosaur National Monument and write the final chapter in Mythical River. The Arizona Commission on the Arts grant, similarly, gave me opportunities for travel and research that otherwise would have been closed to me. Both grants also brought me into a supportive circle of writers who, like me, love the Southwest. I’m so grateful for organizations that recognize the incalculable value of the arts and open these doors.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Can I choose someone I know well? My writing mentor, Richard Shelton, was a wonderful poet, teacher, and champion of the Sonoran Desert. He died last year. We had many, many conversations about writing—really, ever since I showed him some limericks I wrote in the fifth grade—but I find now that I have so many questions I wished I had asked.

How did he balance writing with work? With family? Who were his own mentors, and what lessons did they teach? I suppose losing someone always makes you feel like there were many things left unsaid. I’m lucky he was a writer, because I can reread his books and poems and hear his voice again.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

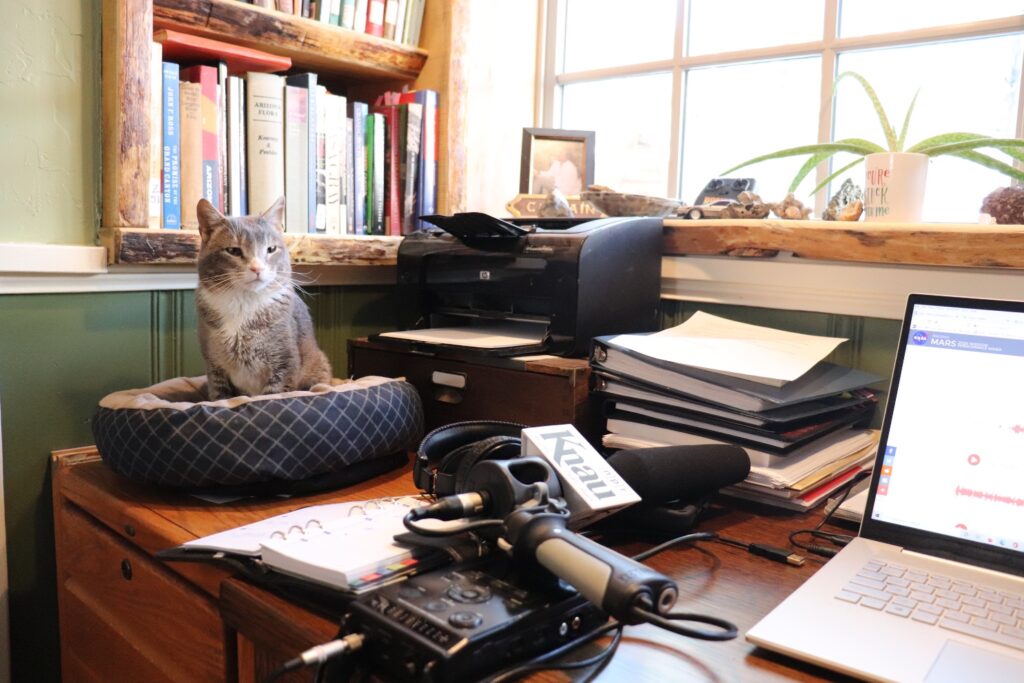

I like being in the middle of things. My desk looks out over the backyard, where I can watch birds and squirrels get into squabbles over the feeders, and it’s got bookshelves on either side stacked with whatever I’m using for research at the moment. It’s a bit cluttered with rocks and leaves and other items I pick up on walks, plus the cat’s basket—though he usually ends up on the keyboard.

In reality, though, I move my workspace around a lot. In winter I like to work closer to the fireplace, in summer I might go to the picnic table outside. Sometimes a change of scene, even just a switch from one room to another, helps me keep putting words on the page.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments