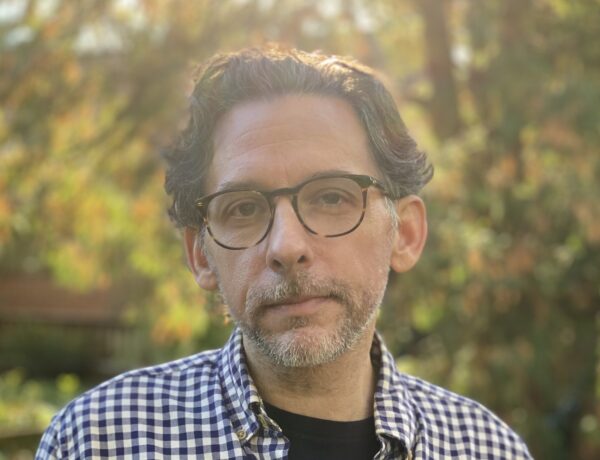

Christopher Blackwell is a Washington-based award-winning journalist currently incarcerated at the Washington Corrections Center where he is serving a 45-year prison sentence for taking another human’s life during a drug robbery.

Raised in the Hilltop Area of Tacoma, Washington, Christopher experienced firsthand the effects of gang violence, drugs, and over-policing in his community. At the age of 12, he experienced his first time being incarcerated, and by 14, he had dropped out of school and became a drug dealer. Christopher spent most of his teenage years in and out of juvenile detention centers before receiving his current prison sentence at the age of 22.

Christopher’s work has been published in many mainstream publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Appeal, and many more. He has also partnered with Empowerment Ave, a nonprofit organization that empowers incarcerated writers and helps them publish in mainstream media outlets.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Christopher, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, thank you for being with us today. Can you talk about your background growing up in Hilltop and your experience with the criminal legal system from a young age?

The best way to look at it is like you’re growing up in an abandoned community. These are communities that are overrun by drugs and gangs. We had plexiglass windows on the first floor of our house because there were so many drive-bys in my community. And I think that when people are growing up in these communities, instead of trying to thrive or be in a place where you can better yourself and grow and develop in the normal pathways children do, you’re kind of living to survive.

A lot of the people as I was growing up in the early 90s, were feeling the repercussions of the crack epidemic. A lot of my friends and I — we were raised by single parents, were raised by our grandparents because a lot of our parents and the key role models who would have played a role in our life were in prison serving time for selling crack. And then me and my friends entered the juvenile system — I entered the system first at 12 years old and never escaped it. I was in the system for getting caught with a simple possession charge for marijuana. And from that point forward, I had been in the carceral system until today. This was the case with the majority of the people in my community.

What led you to co-found Look 2 Justice and become a leader in prisoner-led mentor programs?

Look2Justice emerged in response to years of observing that many organizations working to reform the criminal justice system purported to be “giving a voice to the voiceless.” Yet, we–the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, and families of the incarcerated–are not voiceless!

For a decade many of us inside prisons have tried to push for meaningful change. We constantly struggled. Individuals who were not currently living through the experience of incarceration would take the lead, but it never worked. In 2019 our model changed. My wife, Chelsea and I founded Look2Justice and those in prisons were empowered to voice the direction of our movement.

In the process of doing this work, we quickly realized people had little to no education around the political processes. I mean, my education around how the government worked was little to none. I’ve never seen a legislator in my community and I didn’t know anything about the process of how a bill becomes law or how to change policy.

In response, we began to do training inside of prisons to help people better become civically engaged and understand how these processes work. We also started holding training sessions for formerly incarcerated people and people with loved ones in prison.

Our goal is to give people a way to fight these injustices side-by-side with us — not having to stand behind us, or stand behind larger organizations, but actually empower them. Now we’re holding training sessions for superior court judges and prosecutors facilitated by formerly incarcerated people on the trauma to prison pipeline. We bring in directly impacted people so that these system actors can meet people and see their humanity.

I was lucky to be surrounded by strong leaders who worked for decades to change their lives and then inherently reached out to touch other lives. Their work with me slowly allowed me to see a better path forward. Naturally, I had to follow in the work that they had started by continuing to work to support individuals who need guidance.

Sometimes we just need to help people realize the potential that they have within them and that’s what guys did for me. And that’s what allows me to do it for others. Helping others change into who they were meant to be is how we give back to our communities. It’s how we pay the debt we owe society. And these programs allow us to do that.

Can you speak about your experience in solitary confinement and how it has shaped your advocacy work?

My first experience in solitary came at a young age. I was 12 when I first experienced that feeling of being locked in that cold concrete cell, stripped of everything: human dignity, social interactions, and at times my sanity.

Sitting in places like that really expose us to some scary things. And those experiences were and continue to be a big part of the reason I do advocacy work. We have to change how we treat people. And when you sit in those environments, and experience that treatment, or see that treatment against others, it really makes it hard not to want to do advocacy work.

If we want to have safer communities, we cannot treat people like we do inside our prisons — especially places like solitary confinement. As long as there are people being abused and mistreated in prisons in places like solitary, I will be fighting next to my comrades to end that. If we want people to act like humans, we have to treat people like such.

Your work has been featured in several notable media outlets, including The New York Times and The Washington Post. What inspired you to become a journalist and share the experiences of those impacted by the criminal legal system?

I just fell into the role of being a journalist. If you were to ask me five years ago if this would be my profession, I would have said you were crazy and laughed. It just happened. I wanted to write one story about a friend of mine I had grown up with and when I got into prison and saw him, he was covered in white supremacist tattoos and swastikas. And it just disgusted me that he would succumb to such a crazy environment.

But then when I came to learn about prison more, I realized that he did that for survival in a dangerous prison. And then it led me to want to educate people that this happens. People don’t just come in here and join a gang because they necessarily want to — sometimes people are forced into that for their own survival in these environments. That led me to just want to share that with the world. And then that story, obviously, has spawned all the stories that have followed.

But seeing the change that happens when you have the ability to educate people around the harms of things like solitary confinement, mass incarceration, and the traumas that come through those, it feeds a fire that burns so hot inside of me, I had no choice but to become a writer and continue forward. The pen became my sword and a way to stand up for myself and the many around me who didn’t have a voice loud enough to reach to the outside world.

Deep in my heart, I knew that we, as a society, cannot change this broken system. We just need to help people understand just how poorly it functions and the harm that’s taking place within it. And my role is to share my and others’ experiences within it.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

Can you discuss your collaboration with Empowerment Ave and how it has helped you mentor other incarcerated writers?

My collaboration with Empowerment Avenue began when Emily Nonko reached out in 2020 to help support getting my voice published. Her and Rahsaan Thomas gave me an exceptional amount of support to continue sharing my experiences from prison.

Of course, without my wife, Chelsea, EA would have never come into my life. She was the one who encouraged me to start writing and publishing in the first place. She got my first dozen pieces published and was the one that did all the legwork of connecting with publishers and pitching. That’s how EA noticed me — through a piece in the Marshall Project.

As Emily and I continued to work together, I was given an incredible support team through Empowerment Avenue: Jamie Beth Cohen, Jessica Schulberg and Rachel Zarrow. They were the reason I was able to get where I am. They put countless hours of their time investing in me and working to get me in bigger publications. Because of them, I was able to develop the program that now mentors and develops other writers in prison.

In 2022, Emily Nonko, Deborah’s Zalesne, and Ella Jaffe, founded the writers development program with me. I looked for men that had potential to become journalists from prison and we started creating and publishing content. The program has been extremely successful. We’ve published dozens of pieces, while continuing to develop the mentorship program, which will be implemented through EA in prisons across the country. For me, it’s been about getting as many people as we can to share their perspectives around prisons and what led us here. And EA works to offer me the chance to do that.

Your work has been instrumental in educating society about the injustices and traumas of the criminal legal system. How does it feel to be a voice for those who are often not able to speak for themselves?

All I can say is it’s extremely humbling and an honor to have the ability to speak for my brothers and sisters behind these walls and fences — but it is only possible because they support me. So I’m only in a position because they want me to be in this position to speak for us. So it’s not me, it’s with them lifting me into that position where it’s possible.

You are currently working on a book manuscript about solitary confinement. Can you tell us more about the book and what inspired you to write it?

A few years ago, I was placed in solitary because of an investigation for something that ended up not having anything to do with me. And I was sitting there for a couple of weeks, watching things play out. By this time, I’ve grown up, I’m almost 40. And I’ve completely changed my life. And I hadn’t been to solitary since I’ve been in this frame of mind where I’m now educated and had received a college degree and taken all kinds of classes and started mentor programs.

So I’m sitting in there and watching how people’s interactions are going and how the guards’ interactions are with the individuals that are in there, the other prisoners. And it was just crazy to watch how the treatment was playing out. Most of all, I was focused on this young kid that was 19 years old and had been in solitary for a year. I was watching him constantly get extracted out of his cell, which means he was getting pepper sprayed and hogtied and taken to strip cells where they stripped them of all his clothing, and left him in there under a bright light for a day or two, and then they would bring him back in the unit. And then this process would just continue to go on and on and on.

And I was thinking, “how can this be the way that we treat people?” This kid is 19, he’s been in the hole for a year, and he’s on his way to society in 13 months. I was having conversations with him when he was sitting in there and all I could think was how much hate and damage he’s going to want to cause because of the built up tension and abuse that he suffered at the hands of the DOC while sitting in there. It’s going to be just horrible for society and for him in general.

I was like, “This isn’t what we should be doing. I’m going to take notes and I’m going to write about this whole experience, and what this kid is facing while sitting here. How he was treated — instead of addressing the issues that he had, they abused him. I wanted people to know that. I want people to know that it’s not just people making bad choices here.

A lot of times, it’s people coming into a broken system and not getting an opportunity to get the support they need — not having any kind of consistency or structure in their life. I wanted to show people that. I wanted to show people how we end up with people that go out and harm people from those kinds of spaces and how we can better stop that from happening and invest in those individuals. So they feel like they’re a part of society and not another.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

It would have to be Mariame Kaba. She is a true trailblazer in the field of healing and reshaping how we deal with the disenfranchisement of our communities. Over the years of doing this work myself with the community, I’ve come to see just how hard this work is. There is so much trauma and such a need for healing that collective work can often be extremely difficult to achieve.

I would like to learn from Mariame on how she approaches these struggles — allowing the work to be sustainable. Her strength and ability to do the work in the community is a gift. She reminds us that the work to heal ourselves and our communities can be accomplished in a way that leaves no one behind, in a way where our principles are not compromised, and where we can come to take care of each other as a society, not abuse one another. I want to see this world, and it’s individuals like Mariame that teach us how to get there.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite reads?

Right now, I am reading Becoming Abolitionist: Police, Protests, and the Pursuit of Freedom by Derecka Purnell. Just trying to sharpen my skills around this and learn from others that are doing this work so I can do this work in a much better space. And then I’m also reading a book by Bell Hooks — The Will to Change: Men Masculinity and Love. Because I always want to reshape the way that I’ve been ingrained to think in this world as a male. How I hold space and the air I take out of a room when I’m in a room with individuals that are not males or don’t have the privilege that I’ve been afforded — and making sure that I’m using that privilege in the right way.

And then for fun, I am reading a fiction book that my friend wrote called Liminal Summer by Jamie Beth Cohen. It’s amazing reading her work because she’s been such an inspiration to me and a mentor and an editor in this space for me as I’ve grown and worked towards becoming a journalist.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

2 Comments

Maureen Black

May 19, 2023 at 07:18My son was held in pretrial confinement for more than three years pending trial, and was put in solitary confinement several times, even though the law says you cannot punish pretrial detainees in this manner. He is back in ‘segregation’ (for his own safety) because of an inflammatory press release from the DA. He has lost everything and we have paid almost $100,000 for his private defense. There will be another $40-50k for his appeal. We are selling our home to pay for it. How is any of this justice? I’m going to spend my retirement living in a van trying to get justice for my son, and trying to live long enough to see him free.

Sarah Smith

January 18, 2024 at 05:43He mentions being a voice for the voiceless and speaking for fellow prisoners. He wouldn’t be in prison if he hadn’t taken away someone’s voice by killing them. He had a chance to straighten up when he was first incarcerated but he choose to continue that path, not caring who he hurt or killed on the way. Prison isn’t supposed to be a fun time or a luxury. If you want a good life then be a good person, make good choices and don’t rob, kill, do drugs, etc. He (and 99% of those in prison) made their choices and need to deal with the consequences.