Catherine Gammon is a fiction writer and Soto Zen priest with a diverse publishing history. Her novel China Blue won the Bridge Eight Fiction Prize and was published by Bridge Eight Press in 2021.

Her earlier novel Sorrow was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award and was published by Braddock Avenue Books in 2013. With a background in literature and experience in teaching MFA programs, her shorter fiction has appeared in various literary journals such as Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, and the Missouri Review.

Her latest novel, The Martyrs, The Lovers, will be published in March 2023 by 55 Fathoms Publishing, and her story collection The Gunman and the Carnival is forthcoming from Baobab Press in 2024. Catherine currently lives in Pittsburgh with her garden and cat.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Catherine! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

I grew up in Los Angeles, moved to Berkeley after college, later to Yellow Springs and Iowa City, to Provincetown and Brooklyn, to Pittsburgh to teach at the University of Pittsburgh, back to the Bay Area for Zen training, and finally back to Pittsburgh. And that leaves out a lot of sidetrips. My work, life, and publication histories are equally checkered, and the constants have been my daughter, born in Berkeley when I was very young, writing fiction, and a love of cats.

With writing, as old as I am, it will be hard to be brief, especially if I start at age eleven when writing began for me. By the time I arrived at the Writers Workshop in 1975, I had been writing fiction—novels—in secret for many years, and until that entry, even though I had read some fiction by living writers—Pynchon, Barthelme, Borges, Baldwin, Morrison—I thought of “writers” mostly as dead.

So Iowa was a kind of cold-water baptism for me, even ceremonial, with the ritual of the worksheet—mimeographed in purple-ink in those days—and the sometimes scathing, sometimes helpful peer critique. I turned my attention to shorter fiction there—the workshop format seems to encourage this—and in 1977 my first published short story, “Skinflick,” appeared in The North American Review. That same year, I went on fellowship to the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, another amazing gift to me as a writer, and the town became home for me and my daughter until we moved to Brooklyn in 1982.

I was writing fiction all this time, obsessive rather than disciplined, driven too much by impulse and personal chaos. Fortunately, in New York I got sober, in more ways than one, and a more disciplined foundation took root. Since then, I’ve published three novels and a book of stories that come out of those years (the novels, Isabel Out of the Rain, Sorrow, and China Blue, all with small presses and the stories, Beauty and the Beast, self-published on lulu.com). The current novel, The Martyrs, The Lovers, also reflects that era, but from a radically different perspective. And a new collection of stories, set in the Trump and COVID years—The Gunman and the Carnival—will come out in 2024 from Baobab Press.

Can you tell us about your background in Zen Buddhism and how it informs your writing?

After Isabel was published, in 1991, I taught fiction writing at Pitt until 2001, when I moved to Marin County for residential Zen training at San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm. Training there involves living on a schedule with daily meditation, work, and study, with some weeks or seasons devoted more intensely to silence, meditation, study, and ritual, others more fully to work, but in any season, work is undertaken in this context of dedicated community practice.

So there’s not a lot of room for individual or inward-looking creative work in that life, and when I first went to live at Green Gulch, I set fiction writing aside without knowing when or if I would pick it up again. I just left that open.

After five or six years of residence, though, I recognized that I was writing again, as a writer, not just occasional notes, or phrases, or lines, and when I left training in 2011 it was in part to make a life that had room for fiction and Zen practice both.

I was especially haunted by a long novel I had left unfinished and in storage, based on the Salem witchcraft trials (not yet published). And I had recently become a grandmother and wanted to live closer to Brooklyn, to my daughter and her family. So on leaving I wanted to make a life that integrated practice and the training I had been given with these other aspects of my life.

The first few years “back in the world,” I was a nomad, sometimes teaching at Pitt, spending time at arts colonies and retreats, returning to residential or temple practice, occasionally leading a Zen and writing workshop—at home wherever I was, but generally moving on an idiosyncratic circuit that included Pittsburgh, Brooklyn, Provincetown, the North Shore, and western Massachusetts, Green Gulch, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and visits to Zen groups in England.

In 2016 I stopped and bought the house I had occasionally rented in Pittsburgh, created an ever-expanding garden here, started a small Zen group, and opened my home, zendo, garden, and office to a magnificent orange cat.

So how does all this inform my writing? I think the biggest direct effect of the years of training is the understanding that I can start the day over at any time. Before training and practice I think I thought I had to have the whole day free to write in a truly productive way. Or the whole night after a day of work, something like that. But once I left the scheduled life of the temple, I realized I knew how to start fresh at any moment. And that’s a great unexpected gift.

The other great gifts are the encouragement to question certainty and still to honor whatever arises, to soften resistance, to keep the eyes open, to know where your feet are. There’s a line in a classic Zen poem (“Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi,” attributed to Dongshan): “Turning away and touching are both wrong, for it is like a massive fire.” Like most Zen sayings, this line can be turned in many ways, but in relation to writing and writing fiction I think it expresses this sense of suspension between knowing and not-knowing, which maybe is where the imagination is most alive.

How does your experience as a Soto Zen priest influence the themes and characters in your novels?

Oddly, at least initially, the influence seemed to go the other way around. A central concern in Isabel Out of the Rain is expressed as “we live inside our stories”—and this dwelling within stories is one of the central insights of Buddhist psychology, one that’s emphasized in the lineage I trained in.

Studying our own storymaking is a fundamental, neverending practice, because our storymaking is what shapes our perceptions and actions and views, and if we can’t see what we’re up to, we tend to take what we think as true, which is a fundamental delusion.

So I don’t necessarily see the training in Zen as influencing the themes and characters so much as my life of stories and themes and characters leading me inevitably to this particular family of Zen, which dives so deeply into these questions.

Of course, because I lived in a Zen training life for a long time, elements of that life do come into my work now. But I think the main effect may be that my newer work—the fiction that originated or was completed in the last ten years or so—is somehow more generous and optimistic than what I wrote before training.

This is strange, given the chaos humans seem to be driving the planet into, but despite this, my sense of beneficial possibility in life, in the broadest sense—for humans, animals, plants, the planet, even beyond—seems expanded and intensified by the life of practice, and even though I still explore the shadows in the fiction, I think I must be allowing in more light.

Your latest novel The Martyrs, The Lovers is coming out in March 2023, can you give us a sneak peek of what readers can expect from this novel?

The Martyrs, The Lovers opens on the mystery surrounding the death of Jutta Carroll, apparently at the hand of her romantic and political partner, who dies with her. These fictional characters are based on Petra Kelly, a founder of the West German Green Party in the late 1970s, and her partner, Gert Bastian, whose bodies were found, in 1992, shot, three weeks after their deaths. Reflecting fictionally on these deaths and the lives that led to them, the novel embodies indeterminacy, resisting the temptation to settle on a single—non-fictional—account of reality.

As a German child of her generation, Jutta has grown up in the shadow of World War II, and as the stepdaughter of an American army officer, she experiences most of the 1960s in the US, before returning to Europe in 1968. These contexts feed her rising sense of mission, and the book imagines various steps of her transformation from fragile fantasizing child to charismatic political leader, along with the contradictions that lead to her collapse, before finally introducing a series of dramatizations surrounding her death—“this possible death”—from various imagined and contradictory points of view.

And there’s an extensive bibliography for anyone interested in the non-fictional origins of the novel.

Discover the daily writing habits of authors like Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Gillian Flynn with Famous Writing Routines Vol. 1 and learn how to take your writing to the next level. Grab your copy today!

Your previous novels, China Blue and Sorrow have been critically acclaimed, how did you approach the writing process for The Martyrs, The Lovers differently?

The Martyrs, The Lovers is a departure from the earlier novels in a number of ways, first because it is so heavily researched, and because I didn’t do the initial research with the intention of writing fiction. I was preparing for a different book entirely. But circumstances changed and I had all this research and a compelling interest to look again at what I thought I had understood. The novel grew out of that.

The earlier books also involved elements of research, but the balance was different, and the research was more immediate to the writing. Even with the Salem witchcraft novel, although I didn’t know for a long time what the novel would be, the intention to write fiction came before the research.

Another noticeable difference between Martyrs and the earlier books comes in the way it handles time, starting in a sense with the end of the action, then moving back to a beginning and forward again, introducing and exploring uncertainty, until the final section of the book starts over repeatedly, with contradictory accounts in contradictory points of view. This explicit investigation of uncertainty had some effect on process, but exactly what the effect was would be hard to define.

Beyond this, I would just say that every project seems to present or require and discover its own process, even the several parts of a single novel, and in different stages of its development. And for me, given the patterns of change in my life, these changing life circumstances have also changed my processes.

I wrote Martyrs in the mid 1990s, when I was teaching at Pitt and living within a stable domestic relationship. I wrote intensively throughout the long four-month summers Pitt gave us, and for a month or two into each fall semester, before the academic calendar took over. Nothing else of mine has grown within such a settled container, unless it is the stories coming out next year, written during the Trump and covid years. But how different those years were!

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

By now you can probably tell that I have to resist the notion of a “typical” writing day. Every day of writing depends so much on circumstances, and on the stage of the work itself. If I’m at VCCA, for example, where I’ve often gone in the last decade, I’m utterly disciplined, working in my studio all day, from breakfast until dinner, without breaking to socialize at lunch, maybe taking time out in the late afternoon for a walk.

The structure in that situation provides a container that allows for rigorous focus, the same way the residential Zen center does. And I usually have two projects for a situation like that, a primary and a secondary, one in first draft, one in revision.

At home, even though I live alone now except for the cat, my days vary much more, and there’s a great range of responsibilities. Is it a “writing day” if I’m at the computer only for an hour or two, noodling around with fragments, without a specific intention, just seeing what arises? Or is it only a writing day when I’ve designated a week or two or a month for progress on a particular manuscript, progress with a plan, moving almost aggressively forward, or for review and revision, as if on a timetable? Is it a writing day only if I start immediately on waking up and shut out the world?

All of these ways of working are possible, and I often now start the day without knowing which sort of day it will be. Is it a writing day if I read in bed for several hours, or in warm weather work in the garden, get up or wash up and make breakfast, listen to the news and prep food for the day’s meals, and only get upstairs to my desk at 11, without knowing what I’m going to turn my attention to? Or if instead of going upstairs maybe I do some yoga or qigong or go for a walk and don’t get to my desk until mid afternoon, after lunch?

These are very different sorts of writing days, and still each in its way engages me with writing. This is where being able to start the day over can be so useful. I never used to like afternoon as a writing time. But afternoons are fine, they’re wonderful now. Anything can happen, under any conditions, at any time.

If you could have a conversation with an author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

The funny thing is—even though we’re here talking about writing routines and creative process—I’m not sure the writers out of history I would most like to talk with would really have a lot to say on this topic. Maybe Virginia Woolf, or maybe she would tell me she’d already written all she had to say about this. Emily Brontë, Dostoevsky, Kafka—I would want to ask them about so much else! Or maybe I would just ask them to read something to me, to let me hear their voices.

I imagine that if each could offer an answer of some kind about their process, the most interesting answers would be utterly idiosyncratic, diverse and without formula, like those from the writers in your series. It might be a good question for Tolstoy, but would the answer be too didactic for my taste? What has always interested me most is the book itself, and how it assembles in the imagination of the reader (me!). I don’t know that I really want to ask Dostoevsky or Tolstoy or Woolf or Brontë how they got there. I don’t read biographies of writers, maybe for this reason.

On the other hand, Donald Barthelme might be fascinating on this question and a conversation about it with Henry James would be perfect. I’ve loved them both, so let me settle there, with Barthelme and James.

I’d love to know what you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favourite books you have read recently?

Right at this moment I’m reading Ways of Being, by James Bridle, a wonderful book with a long subtitle (Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for Planetary Intelligence). The last novel I read with interest was Scattered All Over the Earth, by Yoko Tawada, a somewhat mysteriously futurist tale of displacement and identity, constructed around linguistics and movements of language itself.

Two recent favorites are Doom Town by Gabriel Blackwell, a brilliant short novel I recommend any chance I get, and Mothers Don’t by Katixa Agirre, originally written in Basque, then in Spanish, by Agirre, and translated from Spanish by Katie Whittemore.

Another favorite, of another kind, was Villette by Charlotte Brontë, which I read for the first time in the fall with #APStogether, an online slow-reading group hosted by A Public Space. I had re-read both War and Peace and Moby-Dick with them a bit before, and it’s a delightfully fruitful way to savor a great long classic. The best use of Twitter ever, and starting soon on Substack.

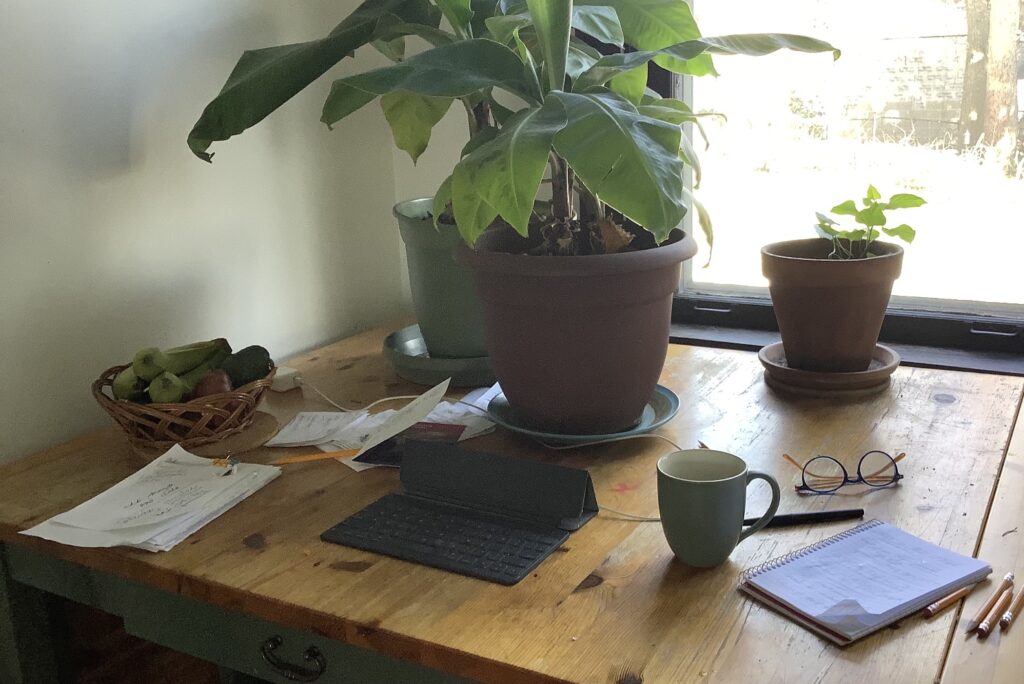

What does your current writing workspace look like?

The primary space is my office—a large makeshift corner desk with an active iMac and a shrouded semi-retired one, many piles of paper, both organized and not, a space heater in winter, a fan in summer, some bookshelves, a cat bed, small filing cabinets, more piles of paper and folders, a printer, several plants.

The secondary space is my bed and bed-table—perfect in winter for reading or a manuscript on a clipboard for making notes for revision. In warmer weather, a smaller, unheated room with a rocking chair is another good reading and revision space. And there’s always my dining room table, with a view of the backyard, for a change of scene.

So that’s just about every room in my little house, except my very small kitchen, and the zendo, or meditation room. I don’t write there, certainly, but along with the garden, these are three workspaces where not-writing gives life to writing.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

1 Comment

Q&A: Catherine Gammon as interviewed on her forthcoming collection The Gunman and the Carnival: Stories by Baobab Press managing editor Danilo John Thomas!

January 19, 2024 at 07:03[…] answered variations on this question several times in recent years (for example, here, here, and here), and it’s interesting to notice how the answer changes. These days my life in Zen and […]