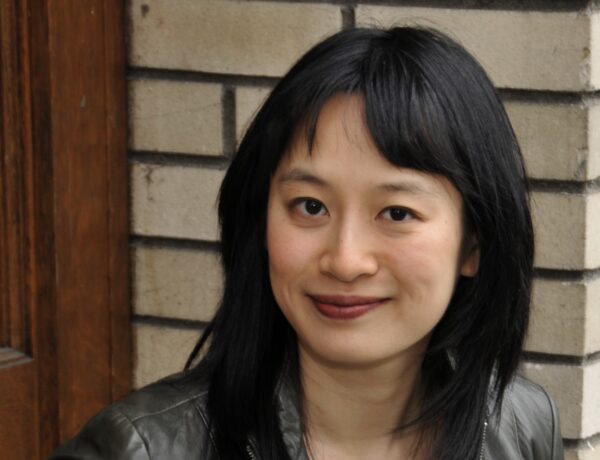

Briallen Hopper, a professor of English at Queens College, CUNY, has a rich educational background, including a PhD in American literature from Princeton University. Raised in Tacoma, she attended Tacoma Community College and the University of Puget Sound, later teaching writing at Yale after dropping out of divinity school.

Briallen’s debut book, Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions (Bloomsbury, 2019), is a celebrated collection of essays exploring themes of love and friendship. This work earned critical acclaim, being named a Kirkus Best Memoir of the Year, a CBC Best International Nonfiction Book of the Year, and a finalist for a Washington State Book Award.

Hi Briallen, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, great to have you here with us today! You have a fascinating background with a PhD in American Literature from Princeton and postgraduate study in religion at Yale Divinity School. How has your academic background influenced your writing style and approach?

I love to read and research. I’m an essayist and often the spark of an essay is an experience or feeling, but at some point in the process I’m going to check out a stack of library books.

I went to grad school to study nineteenth-century US literature but couldn’t get a job in the field. In retrospect I think that was lucky because I’d always felt constrained by academic writing and leaving it behind freed me up to try new things. I still like to write about literature, but now I do it differently. For example, for my first book, Hard to Love, I wrote an essay about Moby-Dick in the form of a raunchy card game as a way of exploring my weird experiences with sperm banks.

After my PhD, I trained to be a preacher, and writing sermons helped me learn to write essays. Instead of working on a big scholarly project for years and years, I had to write something short and engaging in the space of a week. It was great practice for writing for the internet.

Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions received recognition as a Kirkus Best Memoir of the Year and a CBC Best International Nonfiction Book of the Year. Can you discuss the themes and topics you explore in the book?

The book grew out of a viral essay I wrote about spinsters for the Los Angeles Review of Books. People often assume that single people are lonely, but my life as a spinster was full of intimacy and connection. Hard to Love is about a bunch of different forms of love beyond romantic love.

There are essays about friendship, siblinghood, caregiving, and being part of a group of regulars at a bar. Ironically, the book marked the end of my single life, at least for now. For the past three and a half years I’ve been in a romantic relationship with a fan of Hard to Love who slid into my DMs!

You’ve had your writing published in a variety of outlets, from New York Magazine’s The Cut to The Yale Review. How do you approach the different styles and formats required for each of these publications?

I grew up reading women’s magazines and fashion magazines, and I love the juicy, lively, ephemeral quality of pop journalism. I enjoy serious cultural criticism, but I also respect the kind of pieces that will never win prizes or get published in a book but might make someone smile on the subway.

One of my career highlights was being a household advice columnist for Curbed. When someone wrote to ask me how to get guests to take their shoes off or whether to buy a real or fake Christmas tree, I didn’t have to summon up gravitas or polish sentences for posterity. I just had to be helpful and entertaining. Writing those pieces felt like making whipped cream or beating air into egg whites.

I’ve also responded to much more serious writing prompts—some of the hardest writing assignments in the world. I had to write sermons to preach on the Sundays after the Sandy Hook school shooting and the Charleston church shooting. During the early days of the pandemic, when there were refrigerated trucks full of dead bodies parked a few blocks away from my apartment, I wrote about what my neighborhood was going through for The Yale Review. It’s impossible to do justice to these occasions, but it felt important to try. I prayed a lot and asked friends to read my drafts and help me figure it out.

I want to continue growing as a writer and spend more time in genres I haven’t written in as much, like reported journalism and hybrid forms. I like using all the registers in my range, and I want to keep expanding my range.

You live in Elmhurst, Queens. How do your surroundings inspire your writing, and what role does place play in your creative process?

I’m lucky to get to live in one of the most culturally varied neighborhoods in the world. Literally hundreds of languages are spoken here. My apartment is in between Little Manila and Little Thailand, not far from Little Colombia and Little India. My church has services in Mandarin and English; my neighbors speak Spanish and Polish.

Queens reminds me that the world is big and beautiful and complex beyond imagination. It’s humbling and bracing at the same time. I go on afternoon walks every day and talk to friends on the phone and soak up what’s new in the neighborhood. I’m perpetually inspired by the rose gardens and grape arbors that people manage to grow in their tiny front yards.

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

Writing is seasonal for me. I immerse myself in work during the weeks or months before deadlines, and in between projects I take breaks and let my mind regenerate like a fallow field. It took me a long time to accept that rest is an essential part of my process. Lately I’ve started taking Sundays off no matter what, and it’s done wonders.

I write best in the mornings. I teach full-time year-round—during the school year I teach at Queens College, CUNY, and during the summer I teach at Yale—so I try to schedule my classes for the afternoon or evenings. I’ve learned a lot from Esmé Weijun Wang’s wise and practical perspective on writing with limitations. I live with a few chronic health conditions and I lose some days to brain fog or health flares, but on good days I make coffee, wash my face, light a candle, say a prayer, and get to it!

I’ve been writing on MacBook Airs for fifteen years. I like to write in Word, in Focus view, with a blueprint background, in 11-point Didot font. Sometimes I write longhand and then type it up later. I’ve used fountain pens since I was a teenager; my favorite brand is Sailor. I use the Forest app to lock my phone and keep track of my progress.

I’m a social writer and like to meet up for writing dates or what my friends call “writing bees” (like a quilting bee, but with laptops instead of needles and thread). I also appreciate the virtual company and accountability that Zoom can provide. I’d like to thank the lovely people at London Writers’ Salon, who host writing hours each weekday at 8 am London, NYC, LA, and Melbourne time. The rule is you don’t have to write, but you’re not allowed to do anything else. They credit Neil Gaiman for this concept, but Raymond Chandler said it first. Here he is writing to the journalist Alex Barris about it in 1949:

The important thing is there should be a space of time … when a professional writer doesn’t do anything else but write. He doesn’t have to write, and if he doesn’t feel like it, he shouldn’t try. He can look out of the window or stand on his head or writhe on the floor. But he is not to do any other positive thing, not read, write letters, glance at magazines, or write checks. Write or nothing.

I definitely writhe on the floor sometimes, but more often I write!

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that be and why?

Probably Barbara Pym. Partly because I adore her books, and partly because she survived a sustained season of discouragement—after her first six novels, her publisher dropped her and she wandered in the literary wilderness for almost two decades. But even when she couldn’t get published, she still kept writing.

In a talk she gave toward the end of her life, she wrote:

Is it enough just to write for ourselves if nobody else is going to read it? As Ivy Compton-Burnett said in a conversation with her friend Margaret Jourdain, “Most of the pleasure of making a book would go if it held nothing to be shared by other people. I would write for a dozen people … but I would not write for no one.” This is what I feel myself—it is those dozen people that spur me on, even when it seems that I’m writing for myself alone. So I try to write what pleases and amuses me in the hope that a few others will like it too.

I try to write for a dozen people—sometimes a dozen specific people. I write their names on index cards or Post-its and keep them near me as I write.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favourite recent reads?

I’m teaching an MFA class on Daily Writing in the spring, so I’ve been reading some books to prep: Amitava Kumar’s Every Day I Write the Book, Claudia Tate’s Black Women Writers at Work. I’m excited to read Jami Attenberg’s 1000 Words. I’m also a mystery addict and usually spend my commute reading whodunits on my phone.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

It’s important to me to have a desk—it makes me feel organized and legit—but I never write there. I use it as a space to store notebooks and bottles of ink. In practice I like to write on my couch, or at the Queensboro (my beloved local bar and restaurant), or outside. My neighbor and I turned what was formerly a trash area behind our building into an outdoor living room inspired by the lanai in the Golden Girls. It’s painted in bright Miami colors and decorated with fake flowers, with a striped sun umbrella and loveseats with palm frond cushions. When it’s not winter and not raining, that’s where I like to be.

No Comments