Alissa York is an internationally acclaimed novelist and short story writer. Her new novel, Far Cry, is set to be released in March 2023.

She is best known for her critically acclaimed novels Mercy, Effigy, Fauna, and The Naturalist, which won the Canadian Author’s Association Fiction Award. Her short fiction collection, Any Given Power, has earned her the Journey Prize and the Bronwen Wallace Award.

In addition to her fiction writing, York’s essays and articles have been published in notable publications such as The Guardian, The Globe and Mail, and Brick magazine. She has lived in various parts of Canada and now resides in Toronto with her husband, artist Clive Holden. York is a creative writing instructor at the Humber School for Writers.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Alissa! We’re delighted to have you as a guest on Famous Writing Routines. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, could you please give us a brief introduction to yourself?

I was born in Athabasca, Alberta, Canada, to Australian immigrant parents; I grew up there and in Victoria, British Columbia. I was lucky enough to meet my husband, Clive Holden, when I was nineteen and starting to figure out what mattered in life.

I began writing fiction in my early twenties and published my first book, a collection of short fiction, when I was twenty-nine. Five novels have followed so far. Clive and I have lived all over Canada and now call Toronto home.

Can you tell us a bit about your new novel, Far Cry, and what inspired you to write it?

Far Cry began with the sea, hours in the boat with my father, fish glinting in the kelp forests below. Floating, watching, hauling the catch aboard. I left British Columbia when I was seventeen, but I carried its rhythms with me. They were bound to come out sometime.

We were weekend fishers, but the characters in my new novel build their lives around the annual salmon run. The story unfolds in and around Far Cry Cannery and its quarter-mile of boardwalk town, away up Rivers Inlet on British Columbia’s northwest coast. It’s 1922, mid June.

The time has come for Anders Viken, storekeeper and honorary uncle, to give an account of his secret self—from his first home in another land of islands and fjords, to the escape from his family’s loving grip, to the wide-open world of rough living and the laughable dream of love.

As the sockeye flood up the inlet, Anders sets it all down for eighteen-year-old Kit, the only member of his chosen family he has left. Meantime, the heir to this troubled history moves into the adult space left behind by her father’s death and her mother’s betrayal. Oars in hand, she glides into open waters over the great returning school.

Your novels have been internationally acclaimed and have received several awards. How does it feel to have your work recognized on a global scale?

There’s no doubt that recognition, be it local, national or international, helps a writer persevere—especially when it comes courtesy of readers who truly connect with the work. In truth, though, the deep momentum required to write a novel (and another, and another) arises from the act of writing itself.

Your short fiction collection, Any Given Power, has won the Journey Prize and the Bronwen Wallace Award. How does writing short fiction differ from writing novels for you?

I wrote the stories in Any Given Power over seven or eight years, sending them out to journals and anthologies, finding homes for some and not others. Eventually my husband pointed out that I’d written enough for a collection. (I was thrilled and terrified.)

The next book was a novel because that was what showed up. Simply put, narratives used to come to me in the shape and size of short stories; now they almost always come as novels. I love both forms, but the novel seems to be where I’m most at home.

Discover the daily writing habits of authors like Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Gillian Flynn with Famous Writing Routines Vol. 1 and learn how to take your writing to the next level. Grab your copy today!

What does a typical writing day in your life look like?

I write best in the early morning—not every day, but every day possible. First-draft work finds me with pen in hand; the delete key tempts me to start editing too soon. My novels begin with images/ideas that lead to research, which gives rise to new scenes, which lead to more research, and so on. At some point, the characters take the wheel.

You’re also a teacher at the Humber School for Writers. Can you tell us about your experience teaching creative writing and how it’s influenced your own writing process?

I’ve been teaching creative writing for fifteen years—online and in-class, workshops, lectures and mentorships. My work with students continually leads me to refine and reflect upon key tenets of the art, craft and practice of writing (and reading). As a bonus, I get to spend my days surrounded by people who are passionate about the written word.

Can you talk about the role of research in your writing process, particularly in novels like Effigy and The Naturalist?

In-depth research is integral to my process of imagining and building a fictional world—which is strange, given that I initially shied away from “looking things up.” The change came about organically, which is to say gradually but inexorably. It came, in short, in the form of my first novel.

Mercy began simply enough, with the image of a woman living alone at the heart of a black spruce bog. Of course, sooner or later I had to ask myself how much I knew about bogs. The answer came back: “Very little indeed.” And so it went. “There’s a butcher,” the novel revealed at some point, to which I replied, “But I know nothing about butchering.” “Quiet,” said the novel. “There’s also a Catholic priest…”

I began to panic. And then I began to read.

During the ensuing months, I learned all I needed to know in order to write the novel—and a great deal more besides. The lion’s share of the details that fill my Mercy notebooks and files never made it into the book, but does it follow that the knowledge went to waste? By no means.

For one thing, those details supplied my mind with the tools it needed to release each character from their individual lump of stone. For another, ever since then, I feel a sense of expansiveness with regard to the imaginative territory I can inhabit—or, at the very least, explore.

My second novel, Effigy, began when I read an article in the Globe and Mail about Bountiful, BC, home to the Canadian branch of an offshoot Mormon sect. The article got me thinking seriously about polygamy for the first time. There was a buzz around the topic, which got me reading about Mormon history, including a notorious event during which 120 men women, and children were murdered.

Only the very youngest children were allowed to live. Most sources reported that seventeen children survived, but one gave the number as eighteen—a discrepancy that made space for the character of Dorrie, a fictional survivor of a real-life massacre. The rest of the novel grew up around her.

The Naturalist was my fourth novel. It came about in response to an application I made for a fellowship that requires writers to challenge themselves to grow as artists. I asked myself what such a challenge would look like, and the answer came back: write a novel set in the Amazon (a place I’d been fascinated by since childhood).

As always when faced with an overwhelming prospect, I started to read. The narratives of nineteenth-century naturalists piqued my curiosity, and the symbiotic relationship between research and the imaginative process began anew.

You’ve also written essays and articles for publications such as The Guardian and The Globe and Mail. How do you approach writing non-fiction compared to fiction?

I find non-fiction writing both harder and easier than fiction writing—perhaps because it holds me in a lighter spell. Whatever the form or genre, I try to think clearly and compassionately about a specific group of humans (and very often their fellow creatures), consider what they need and whether they get it or not. More than anything, I try to get every sentence right.

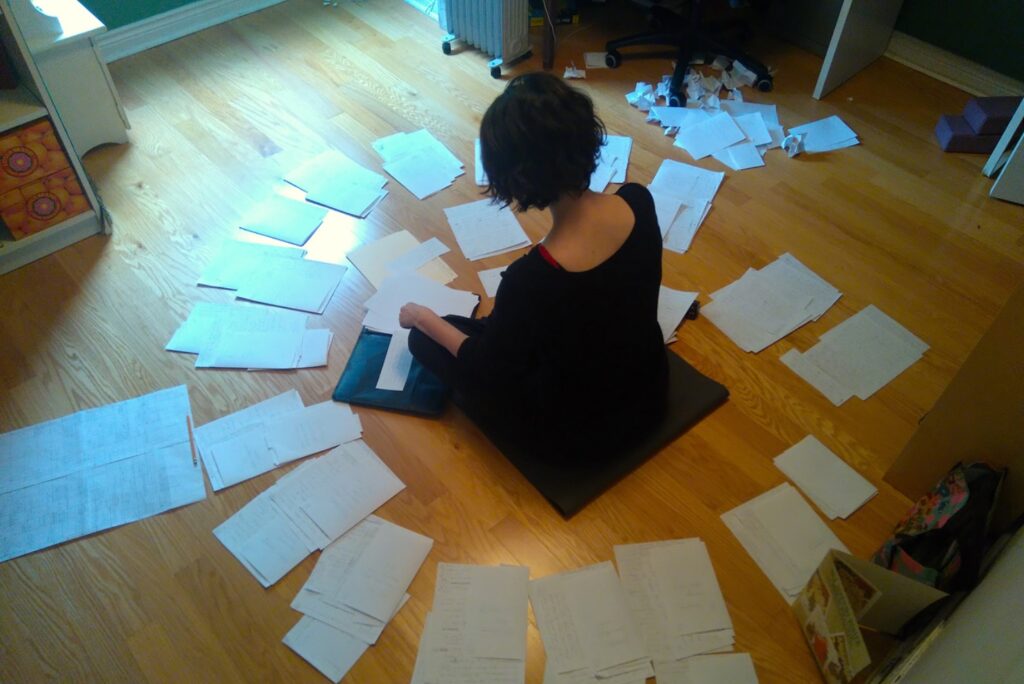

What does your writing workspace look like?

I have two writing desks—one crowded with computers, notebooks and sticky notes, the other kept clear for first-draft writing. The deeper I delve into a novel-in-progress, the more pages and file folders build up on the nearby shelves. Sometimes I arrange them on the floor. Photos of Clive keep me company while I write, as does a small golden cat.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments