Alice Jolly is a novelist and playwright. Her fourth novel Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile was runner up for the Rathbones Folio Prize 2019. That novel was also on the longlist for the Ondaatje Prize and was a Walter Scott Prize recommended novel for 2019.

Alice has also won the Pen Ackerley Prize and the V.S.Pritchett Prize. In 2021 she received an O.Henry Award (for the twenty best short stories published in the US). She teaches creative writing at Oxford University.

Looking for inspiration to help you achieve your writing goals? Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights into the routines, habits, and techniques of some of the most celebrated authors in history.

Hi Alice, thanks for joining us today! Your novel Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile has been described as a “rolling free-verse epic” that tells the story of a servant woman in 19th-century rural Gloucestershire during a period of political upheaval. Can you tell us what inspired you to write this book, and how did you come up with the unique form of free verse to tell Mary’s story?

When I was at school, I had an inspirational history teacher who was fascinated by Marxist narratives. She introduced me to E.P. Thompson’s great book The Making of the English Working Class. Many years later, when I came to Stroud in Gloucestershire, I spent many days walking through this amazing landscape. I often passed through the Stroud Cemetery. As with many cemeteries up and down the country, Stroud has many grand marble graves and stone memorials. But there is also an unmarked grassy bank where the bodies of paupers were dumped.

I began to wonder who those people were and what we know about them. I found very little documentary evidence. Then one day, as I was walking in the cemetery again, I heard the voice of Mary Ann Sate and I wanted to write down her story. I had no idea of writing a verse novel. But I did know that I needed to find Mary Ann’s actual voice, not the voice that she might have used when writing. She speaks in Gloucestershire dialect, and her way of expressing herself is dense and knotted. So it seemed natural to break the text up according to the rhythms I was hearing. Also, Mary Ann herself is interested in poetry so I felt she would like her book to be written in that way.

The novel deals with some very heavy themes, including abuse, poverty, and political unrest. How did you balance these weighty subjects with Mary’s own personal story and her relationships with the other characters in the book?

Your question is interesting. I always want to write a book which is both epic and intimate. That is a huge challenge. This relates particularly to historical fiction. You want the reader to come away knowing more about the historical period and the events you are writing about but, equally, you need to tell a good story. You always have to ask yourself – why can’t this book be non-fiction? Just re-mixing non-fiction accounts is not enough. You have to really bring some imaginative and dramatic element to what you are writing otherwise what are you adding?

It is hard to find ways to introduce historical information which does not feel clunky and intrusive. I was helped by the character of Mary Ann herself. Her life is extremely limited but she had an interest in the world around her. Also, the book is designed so that she finds herself working for a family who are engaged in bigger social struggles.

In terms of the balance of the ‘heavy’ and the ‘light’ Mary Ann herself also helped me to find both. She is a person entirely without self-pity. And she has an enormous love of the small things in life. I think that is a particularly female gift and I hope that brings light to a story which is, overall, quite painful. Also, Mary Ann is religious. She believes in the after-life. She is looking to a world beyond her immediate situation and she has absolutely faith that she will rise again on another shore.

The Chartist movement and the Swing riots of the 1830s, both of which were significant moments in British history, feature prominently in the book. How did you go about researching these historical events, and how did you balance historical accuracy with the demands of storytelling?

I often hear historical novelists discussing the question of whether to prioritise historical accuracy or to focus on telling a good story. To me, it is absolutely clear that you need to deliver both. Historical accuracy does matter to me and so I need to weave my story around real events. But, of course, absolute accuracy is impossible. I tend to think in terms of ‘embroidery.’ In other words, you take an outline of events and fill in the gaps.

Also, the word ‘plausible’ is important. There is so much about the past that we simply cannot know. But we can use the evidence that does exist to create scenes and events which could have happened. It is very, very important that we are honest about the past. In particular, we must never strip it of its nuance. We can never get a final answer, but we need to keep researching, questioning, thinking and welcoming new approaches.

Do you struggle to stay focused while writing? You’re not alone! That’s why Famous Writing Routines recommends Freedom – the ultimate app and website blocker for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Chrome. With over 2.5 million users, Freedom helps writers stay on task and avoid distractions. Get started for free today and reclaim your productivity!

The novel is quite long, at 640 pages. How did you keep the momentum going and maintain your own energy and enthusiasm for the project over such a long period of time?

The novel certainly appears to be long. That is because of the way in which it is laid out. There are not, actually, many words on each page. However, the question of how one keeps going is definitely worth considering. I redraft many, many times. My books will tend to be rewritten at least six or eight times, sometimes more. These rewrites are not minor adjustments but really taking the novel to bits and putting it back together again. It is very, very hard.

I still find myself gasping at just how hard it is. I think the problem is that, by the time you are halfway through the writing process, the initial enthusiasm you had for the project has disappeared. But you cannot give up. Sadly, too many novels read like good first drafts. You have to push on beyond that. Sometimes by the time I get to the copyediting stage, I am literally nearly crying with boredom and frustration.

I am currently trying to finish a new novel. I find myself avoiding talking to people because I will have to say, ‘I have nearly finished the book.’ The problem is that I have been saying that for two years or more, people are starting to look at me like I have lost my mind. I might, in fact, have lost my mind.

You were recently awarded the O.Henry Award for your short story writing. How does writing a short story differ from writing a novel or a play, and what do you enjoy about the shorter form?

The great thing about a short story is that it offers the opportunity for experimentation. The novel is, actually, surprisingly constrained. You make some decisions relatively early on in the process about how the novel will work and then you are tied into those decisions for years to come. With a short story, you can spend a couple of weeks on something and, if you decide it isn’t working, you can just chuck it aside. Also, there are experimental things you can do in a short story which will never work in a longer text. We have to keep Laurence Stearne in mind. ‘What is strange must be short.’

You also teach creative writing at Oxford University. What do you hope your students take away from your classes, and how does teaching influence your own writing?

Teaching can be quite difficult because sometimes you feel that you are selling people a dream that doesn’t exist. I try never to talk to my students about the world of agents, publishing, books sales etc. To be honest, that is just going to bring us all down. I tell them that there are two different things. The writing itself and the bureaucracy of writing. You have to keep those two things in different boxes. I bring my students back to the text again and again. We focus on the words. The sounds, the rhythms, the shape of the text or the authenticity of the voice. That makes everyone feel good, excited, uplifted. We all need to come back again and again to the love of the word. That is all that really matters.

How has your writing process evolved over the course of your career? Are there any particular writing rituals or techniques that you find helpful?

I take a very long time to write a book and I wish I didn’t. I always think I will speed up at some point. But the problem is that each book is a new set of challenges. Over time, you do get better at spotting a red herring. I used to write whole sections of books which I then scrapped. I am better at not doing that. But I do have a notice above my desk which says, ‘Do not argue with the process.’ That’s a reminder that we can all sit at our desks feeling angry with ourselves because we are two years into the book and we still don’t really know what it is about. But that just wastes more time.

The way you write a book is the way you write a book. You have to accept it. I think that, in creative terms, there is really no such thing as ‘wasting time.’ However, you do need to keep turning up at the desk. I just tell myself, ‘There is nothing in the world that can’t wait three hours.’ That is true and it helps.

If you want to write a book, you do have to think about the sacrifices that you may have to make. It may not be possible to write a novel and have a tidy house. I think I have lost a lot of friends during the writing of this most recent novel. I don’t call people back. I often don’t answer emails. I regret that but it is the cost of the writing. I get better at being selfish as I get older.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

I would like to meet Hubert Selby Jr (Last Exit to Brooklyn) and William H. Gass (Omensetter’s Luck). I also keep returning to Ken Kesey (One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest). For me, these novelists are the consummate writers of voice. For them, it seems everything is rhythm and sound. I think if I actually met them I would be too over awed to ask anything at all. Also, it seems to me that they write from such a deep place that it would be impossible to ask ‘how.’ Good writing is not received in the head, or even the heart, it is received in the gut. You simply cannot subject that writing to logical literary or critical analysis.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favorite recent reads?

I loved Elizabeth Lowry’s recent book The Chosen (a novel about Thomas Hardy). I have just reviewed Tan Twan Eng’s book The House of Doors (out in May 2023) and it is stunning.

During lockdown I went back to some of those fat, classic novels. I read Clayhanger by Arnold Bennett and I was absorbed in that book in a way that I am never lost in contemporary novels. I also discovered One Thousand Streets Under the Sky by Patrick Hamilton. That man can really write. His books are grueling but incredibly honest. Overall, Shirley Hazzard and James Salter are possibly my favorite writers.

I keep Omensetter’s Luck by William H. Gass on my desk. If I am writing and I can’t find the right rhythm then I pick up that book and read a few pages. I find then that I can tap into the cadences of what I want to write.

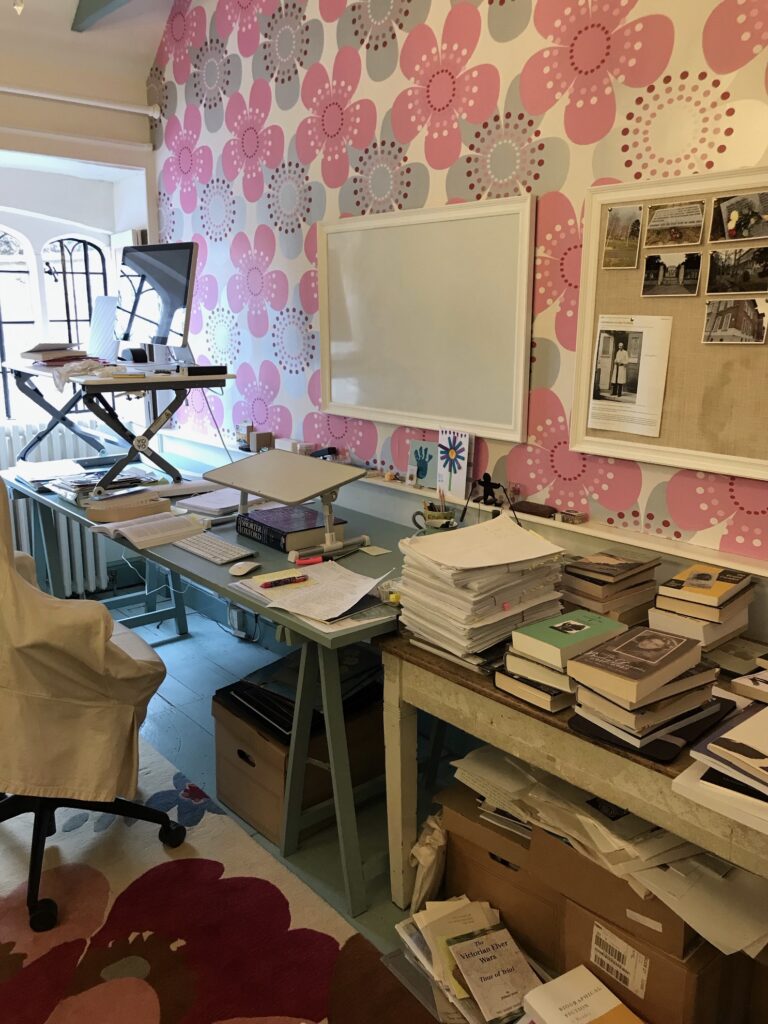

What does your current writing workspace look like?

When we moved into this house fourteen years ago, I designed myself a rather stylish office space. Things have gone downhill since that time. My current writing space looks like a serious case of what I would describe as ‘research fever.’ I have a large writing desk but, nevertheless, I had to put another whole big table into the room just to pile up the books I am using to research the novel which I am finishing now.

I also have nine drafts of that book printed out. (I keep old draft and put them in the attic as I know that writers sometimes sell those drafts for a lot of money – well, we can all dream). Having said that, when I have finished this new book (when, when) I will have a massive and brutal clear out. The physical clutter becomes mental clutter and I am looking forward to a Brave New World. Clear office space. Thin and simple book. As you get older, the boat starts sinking and you won’t survive if you don’t chuck a lot of stuff (both physical and emotional) overboard.

Affiliate disclaimer: Some links on this website are affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through these links, but only promote products we truly believe in. We disclose affiliate links and give honest reviews.

No Comments