Adrian Shirk is the author of Heaven Is a Place on Earth, a personal odyssey of American utopian experiments, and And Your Daughters Shall Prophesy, a hybrid-memoir exploring American women prophets and mystics, named an NPR ‘Best Book’ of 2017.

Shirk was raised in Portland, Oregon, and has since lived in New York and Wyoming. She’s a frequent contributor to Catapult, and her essays have appeared in The Atlantic, Lit Hub, and Atlas Obscura, among others. She teaches in Pratt Institute’s BFA Creative Writing Program, and lives at The Mutual Aid Society in the Catskill mountains.

Each week, we publish a new daily writing routine from a famous author. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

Hi Adrian, great to have you on Famous Writing Routines. We’re really excited to talk to you about your writing routine and process. For those who may not know, can you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

I’m an author of two books of creative nonfiction – And Your Daughters Shall Prophesy: Stories from the Byways of American Women and Religion and Heaven is a Place on Earth: Searching for an American Utopia (both from Counterpoint Press).

I’m an essayist, and it is through essayistic writing that I get to explore and develop all of my other interests and questions: utopianism, theology, feminist history, urban resistance movements, architecture, pop culture, pedagogy, plants, and my own lived experience, or at least the parts of my lived experienced I am, at the moment, most vexed by.

I love how portable and mutable writing is, and how much it can accompany every part of my life. I’m an agent at Drift(less) Literary where I represent a select number of authors, and a faculty member of the BFA Creative Writing Program at Pratt Institute where I serve as the Writing Lives Advisor. In my spare time, I run an experimental cooperative artists’ residency out of my home in the Catskill mountains.

Do you remember the first moment you realised you wanted to become a writer?

I’m not sure when I realised this. I was writing all the time as a kid – even making little books that my stories were gathered into – but it wasn’t an identity. I do have a threshold moment, though, I guess, when I was in 8th grade, at the end of middle school.

There were, if I recall, two encounters with literature that happened that year that forever changed me: the comics and graphic novels of Lynda Barry, that my teacher gave me, and the short story collection Revenge of the Lawn by Richard Brautigan which had been sitting on a bookshelf in my parents’ basement growing up.

There was something about these books, where I guess they were my first experience reading what you might call “literature” without having it assigned in school, and when I say “literature” I mean writing that is primarily an art object, to be engaged as art, versus simply as an interesting story (like much of the wonderful YA fiction I read).

Those books really woke me up, the potential for weirdness and experimentation and play in the writing process, its endless possibility as an art form, the way that it could go in any direction or style that you want it to, break rules, tell any story in any way you want. So yes, Lynda Barry and Richard Brautigan for some reason cracked that realisation open in me, as the activity I most wanted to do all the time, whether or not I would ever be paid for it.

Can you take us through the creation process for your book, Heaven Is a Place on Earth?

Heaven is a Place on Earth emerged in much the same way as my first book did, as well as my shorter writing projects: I became obsessed with a subject I loved, which was related to a practical and moral inquiry I was living through in real time, and so the book projects in a way become a space for me to gather notes, ideas, thoughts, research, annotations, and conversations that I am already gathering and gleaning in my daily life.

For Heaven, though, I had long loved the histories of utopian experiments, and I had always been gripped in general by the way groups of people build worlds for themselves – religions, cities, revolutions, communities. I loved the enormous diversity and imagination of utopian experiments, the ways that – in spite of risk and failure – groups of people attempt constantly to build themselves a better world, resist the terms that the oppressive empire has required of them.

Utopianism in that way always has this way of pulling back the curtain, revealing the Wizard of Oz so to speak, the artifice of our culture’s rules and mores, and then the invitation that, in fact, we can do anything we want, though we may die trying.

And then I think I also was in a real crisis of my own, in my mid-twenties, taking care of my terminally ill and disabled father-in-law, working full-time, completely isolated and barely able to make ends meet in late-stage capitalism that had seen an absurd gulf in inflation and wage stagnation, and needing – if only for my fantasy life – a way of imagining all of the possible ways I could innovate a strategy out of this pit – a strategy which would still, of course, need to include work and care, but also beauty and rest. So, I was like, how had other people done it? And what were all the different reasons they’d done it for? And what were the costs?

Because I was so strapped for time and energy at that time, I more or less amassed a pile of brief sketchy notes whenever I could, just adding to them – what I called “utopianotes” – in my computer, without a clear plan or arc. I knew I was writing about utopian experiments, but that was it.

Every time I read something relevant, or talked to a friend, or saw a movie, or bridged a connection, I’d write it down. Eventually, a year-and-a-half in or so, I looked at all of those “utopianotes” as a whole and began to see a shape, a kind of logic, a story: it was in part my own story, a constellation of my own values and dreams, and it was also a story about American utopianism as a wild, rangy history and also a living, breathing thing, not just something locked in the past, not just relegated to the 19th century in the guise of the Shakers or the Oneida community or even the oft-fabled failed hippie communes, but as a set of strategies and ideas still living in our food co-ops and urban homesteading movements and Waffle Houses on Tuesday mornings and anarchist cooperative houses, and, well, essentially anything that the laws of capital and conquest were supposed to make impossible, which capitalism was designed to prevent, but which happened any way and are always happening.

So eventually I began to build out fuller chapters, based around particular themes, and then broader travelogues about communities I had visited, and only then could I see where my own autobiographical throughline fit in.

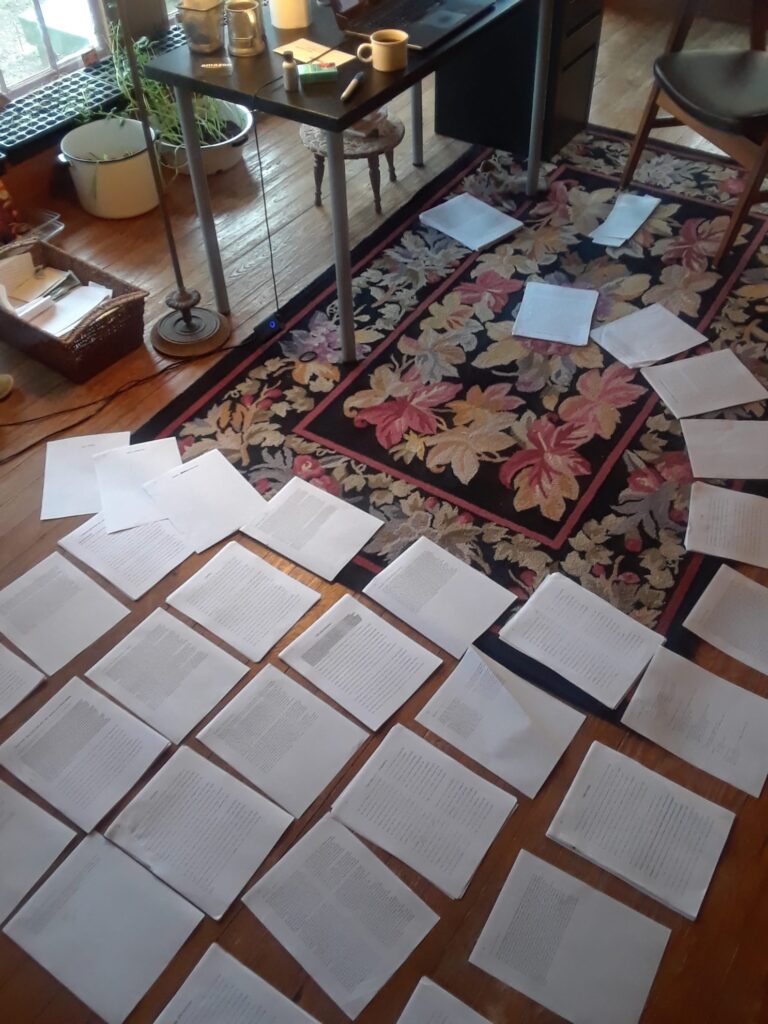

A lot of that process was about building on the original “utopianotes” I had chronicled in my densely-packed weeks, so it worked for a while almost like a jigsaw puzzle for which there was no key, big hunks of writing I was stitching together as patchwork, and then I was eventually sounding out the places in the writing that called for deepening or expansion.

I think the weird part is that I was never writing a memoir, in that I was not so much writing about my memory of the past, but rather reporting on my life in the present, so in the final months I was finishing up the book for my publisher, I was basically narrating in real time in a state of total mystery, as my own communal experiment (which I never could have guessed existing at the outset of my desperate “utopianoes” three years earlier) began to respond to the emergency of COVID.

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

I used to have fairly reliable habits, especially during the breakneck years I wrote most of this book: I wrote something nearly every night after work, and would give myself at least one full day of dedicated “writing time” whenever I could get it on the weekends.

I put “writing time” in quotes because even at vast stretches, I might not actually be composing words but rather staring, muttering, reading, thinking, wandering, and occasionally writing with the expressed intention of the book’s subjects, themes and questions. I like to be able to really mentally spread out.

So I had to build very clear goals for when and where I would get “writing time,” continuous stretches of hours where I could really marinate and build creative momentum, but as my life has transformed over the past few years – as it has become radically more fluid and flexible – I find myself losing almost anything resembling a habit.

Do you have a target word count or a set amount of hours you like to write each day?

I used to write every day, even just a little bit, for fifteen minutes – though there was never a word count goal. I have, in the last couple of years, not felt the need to do that. So now it’s more like, I do have a practice for myself to make sure I do something creative every day, even for just fifteen minutes, but that could be anything: writing, yes, or a dance, a song, editing photos or videos, an audio recording of text.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns affect your routine?

The pandemic and lockdown profoundly affected my routine, for a number of reasons. A few months before lock-down, in part because of the journey that the book had led me along for many years, I ended up moving up to the Catskill mountains to develop a beta-artists’ residency program, in what would be my new home.

When the pandemic surged, I started teaching exclusively online, and so my daily and weekly life significantly opened up, eliminating hundreds of hours once gobbled up by commuting, navigating housing logistics, and we had finally been able to secure subsidised full-time care for my father-in-law.

So I had new responsibilities – to the land, the residency, the flow of visitors – and fewer of so many I had been accustomed to, so my writing process became much more improvised, and the forms I was drawn to work in began to radically broaden.

I did however finish the full draft of Heaven during the first several months of the pandemic, and for that time, I did need at least two full days a week of that old “writing time” – the squirrelling myself away from late-morning to late-evening to wander around in the world of the book, to read and re-read my source texts and also my own words, to edit and revise as a generative act. But looking back, I now find that mode to be somewhat tiring, though it was effective – and I’ve always liked a deadline for that reason – but I am beginning to open myself up to new possibilities.

For instance, I suppose my routines – if they can be called that – orbit around collaborations these days. I’ve been working on collaborative projects with different people, and for each of those we’ve established one day a week of either in-person or Zoom meetings dedicated to the project at hand, even if it’s only for an hour. The idea being that any project, of any kind, if even just a regular, habitual form of attention to it is given on a regular basis, then it will just come into being.

What does your writing workspace look like?

I also used to work, for many years, at a dedicated desk, and for a while, in a small sunroom that had been converted into a little study for me. Those were the years where I wrote anywhere from fifteen minutes a day to several hours a day, depending on what was possible.

The desk and the study would ebb and flow in cycles of extreme tidiness, and then slowly over weeks become cluttered with book stacks, notes, mail, paper, totems, until I had to do an overhaul back into order. There were benefits to both states.

These days, I write everywhere: the living room floor, the kitchen table, the back deck, the garage, hotel rooms, aeroplanes, walking around speaking into an audio note app which I will eventually convert into text at some point. I no longer have a single workspace. Maybe that will change. Maybe it won’t.

Before you go…

Each week, we spend hours upon hours researching and writing about famous authors and their daily writing routines. It’s a lot of work, but we do it out of our love for books and learning about these authors’ creative process, and we certainly don’t expect anything in return. However, if you’re enjoying these profiles each week, and would like to send something our way, feel free to buy us a coffee!

No Comments