Lisa Hsiao Chen is the author of Mouth (Kaya Press) and Activities of Daily Living (W.W. Norton), a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel and Gotham Book Prize; longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize and the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction; and selected by The New Yorker, Vogue, and Publishers Weekly as a Best Book of 2022. Her work has received support from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Vermont Studio Center, and Art Omi: Writers. Born in Taipei, she lives in Brooklyn.

Hi Lisa, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, we’re so glad to have you here with us today! Your latest novel explores the themes of work, life, and the passage of time. Can you talk a bit about what drew you to these themes, and how you approached writing about them?

Sometimes I think time can be broken down into occupation, vocation, and death. The first is what makes money, and takes up most of our time as adults. Vocation (I call it “projects” in the novel) is what we’re burning to do, even if we’re not paid for it. Vocation can sometimes be occupation, if we’re very lucky, but most of us are not. The last, death, is ultimately what gives our life form.

All three were on my mind when I started writing the book. I had recently quit a full-time job, swapping occupation for freelance work plus vocation, thanks to the intervention and generosity of my spouse. Our parents were getting old. I somehow became middle-aged. Time, and how to spend it, had to be reckoned with.

I didn’t, and still don’t know how to write novels. So my approach was to write freely at first, without overthinking genre or what the ultimate shape of the book would be. Only later did the form emerge. As Tehching Hsieh would say, “Life is a life sentence. Life is freethinking.”

One of the central characters in the novel is the enigmatic performance artist Tehching Hsieh. What drew you to his work, and how did you go about researching him for the novel?

Like Alice in the book, I encountered Hsieh’s work early on as a kid when I first saw him in a magazine. I was drawn in, in part by his Asianness at a time when there were few faces like mine doing the kind of art he was doing. And then of course there was his art, which magnified in my mind around the same time I became more preoccupied with time itself. It’s hard to say now which came first. Writing a novel is a long game; in Hsieh I found a model for the endurance necessary to see a project all the way through, as well as the philosophical depth to explore everything from carceral time, our 24/7 work cycle, and more.

In terms of research, I owe a lot to the splendid monograph of Hsieh’s work, Out of Now (MIT Press) by Adrian Heathfield and Tehching Hsieh. Of course I turned to the internet, too. From there emerged “Art Without Work: Tehching Hsieh’s No Art Piece and the Ethics of Laziness,” a masters thesis by the art scholar Brian Leahy. Brian’s killer thesis led me to Boris Groys’s hilariously trenchant essay “The Loneliness of the Project,” which became an important framing device for the novel. The reporting of C. Carr, probably one of the few, if not only, journalists focused on performance art at the height of Hsieh’s heyday in 1980s NYC, was also essential reading.

I also had intentions to visit physical archives, but got mired in online technical difficulties trying to arrange it, and gave up. By that point, I was in danger of over-researching anyway (and not writing).

The novel also explores the challenges of caregiving, particularly for a family member with dementia. Can you speak to the personal experiences or inspirations that informed this aspect of the story?

My real-life stepfather began developing symptoms of dementia and eventually died of it in the duration of writing this book. This novel couldn’t have been written without these galvanic events. Most of us don’t encounter the world of professional caregiving, or ourselves as caregivers, until we’re forced to. (I’m not speaking of parenting, of course.) It really is, like Sontag says, like crossing over from the kingdom of the well to the kingdom of the sick.

There was a month of time after my dad landed in the hospital and later, at a skilled nursing facility, when I felt my life give over to his. Nothing else mattered. Those were days of great anxiousness, but also enormous, intense clarity. The dimension of caregiving as work, as part of our life’s project, became essential to my idea of the book.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers who are trying to find their voice and break into the industry?

I struggle with this voice question. I think we all have an innate voice, the one that meets the page. Pay attention to how your sentences swing. That’s where the voice lives.

The “industry” is not a monolith, although it can seem like one, especially when you’re trying to get published. What we’re trying to do as writers is find our readers, and there are multiple ways to do this. Affinity is essential. Find the journals, the writers, the books, and the community with whom you feel strong affinity, and give to that community the way you’d like to be received.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

This interview is catching me at a moment when my routine is broken. But generally speaking, mornings through early afternoon, no more than four hours. And trying to remember that writing is reading. Taking the subway. Talking and corresponding with friends. Seeing art and going to the movies.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Herman Melville. Gwendolyn Brooks. Viktor Schlovsky.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favourite recent reads?

Merine Arsanios’s Autobiography of Language (Nightboat Books)—one of those books, that once finished, you know you’ll need to reread again for its fierce intelligence and contrapuntal moves. A book in which a woman’s father is dying in a hospital bed as she herself becomes a mother and “every ‘I’ feels like a fraud and a necessity”, “every language a reminder of an absent one.” Arsanios gets to the heart of how we (especially migrants, refugees and exiles) wrangle, through words, our place in the world.

I’m about a third way through Animal Joy (Graywolf Press) by the psychoanalyst and poet Nuar Alsadir, a book I hadn’t thought I’d want to read (I am, by disposition, a rather dark-minded person suspicious of books with the word “joy” in the title). It’s a book about throwing off our public masks, a manifesto for creative eruption as an antidote to soul murder. The precision of Alsadir’s thinking sparks against the book’s unruly, sometimes dizzyingly associative jump-cuts.

Let me include a film here: Miko Revereza’s No Data Plan, an essay film of the filmmaker’s cross-country train ride. (Revereza was an undocumented college student on the East Coast at the time, which made train travel a necessity.) The greatest thing about being a creative person is that boredom is damn near impossible: everything can be raw material. A true feat of mother-of-invention technique, Revereza’s film, shot entirely with his phone, combines arresting and meditative footage of train interiors and landscape with non-diegetic phone calls (think Chantal Akerman’s 1976 News from Home) into a portrait in time of a family and self fractured by migration, borders, diaspora.

I was excited to learn that Revereza has a poetry book, Nowhere Near, forthcoming, selected by John Keene for publication by Wendy’s Subway, as well as a new film by the same name. How cool. Cannot wait.

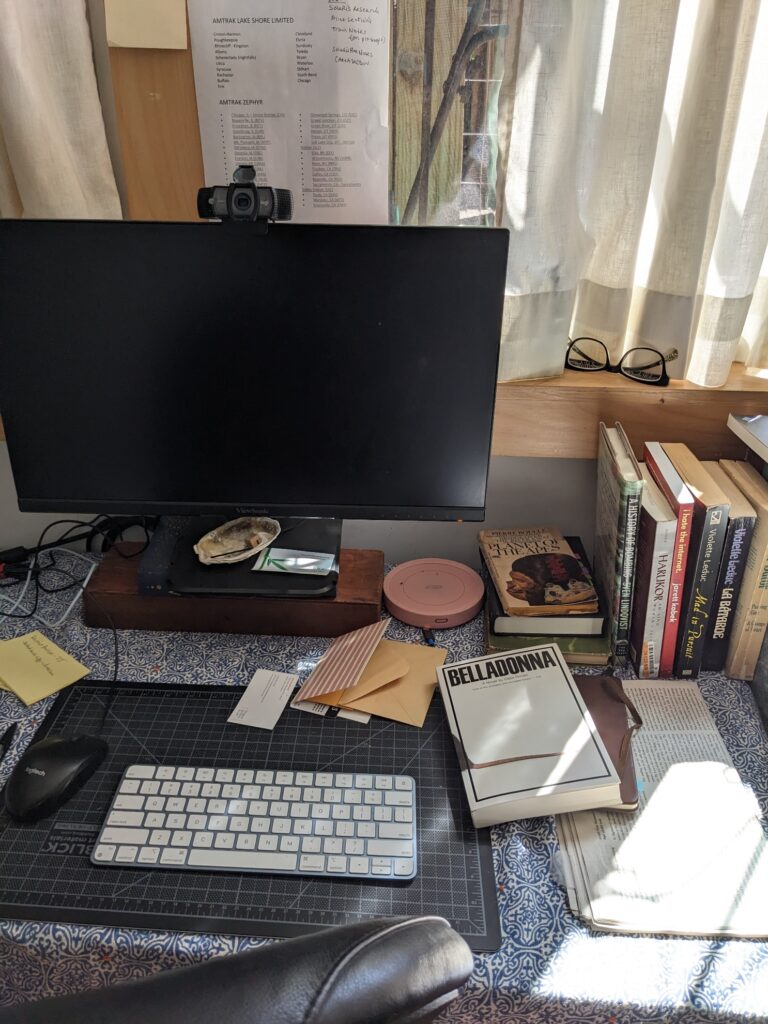

What does your current writing workspace look like?

I spend a lot of time, it seems, avoiding my actual workspace. The ergonomics are excellent and yet the set-up can induce dread. Instead, I often write in a reading chair, at the dining table, standing with my laptop propped on a stack of books at the kitchen island, in libraries and at the cafe at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn, on occasion.

No Comments